Lessico

Agresta o agresto

Tipo di vite con uva che non giunge mai a piena maturazione, e succo di sapore pungente e acido che se ne ricava. Agresta e agresto non derivano da agro nel significato di campo (greco agrós, latino ager) bensì da agro nel significato di aspro derivato dall'aggettivo latino acer-acris-acre che significa acuto, aguzzo, appuntito, tagliente, aspro. Il latino acer deriva dalla radice indeuropea *ac- che indica acutezza, presente per esempio anche nel greco akís = punta.

In base ai dati raccolti da www.vivc.bafz.de il nome scientifico dell'agresta è il linneano Vitis vinifera - vite comune o vite euroasiatica - e dell'agresta esisterebbero due varietà: ad acini neri e ad acini bianchi. Un tempo, soprattutto nel Medioevo, quando il limone era difficilmente reperibile, il succo veniva impiegato come elemento acidificante nei condimenti. Entrava nella preparazione di una salsa per arrosti e bolliti (salsa agresto) a base di zucchero, aceto, brodo, spezie ed erbe aromatiche. Attualmente viene usato al naturale o leggermente fermentato sia dalla cucina classica sia da quella rustica (per esempio, vegetali conservati sotto agresto).

Agresta

This is the Italian word for the verjuice grape (see also entry for Verjuice). The corresponding word for the verjuice made from it was agresto. The verjuice grape was cultivated in both Italy and France, and was also used for conserves and jellies. (Richard Bradley, 1736)

http://ds.dial.pipex.com

Verjuice

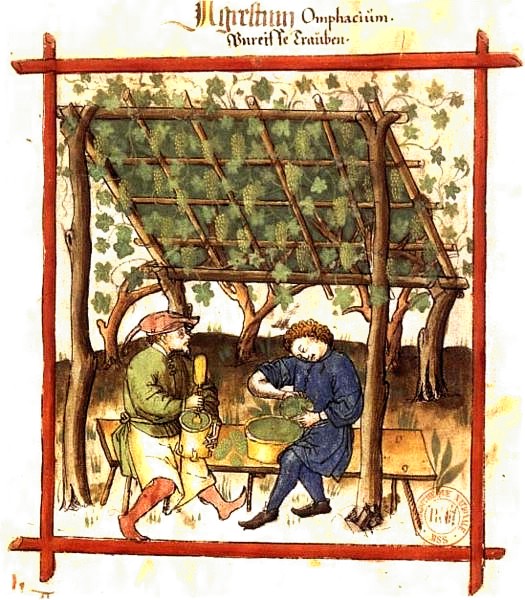

Picking

green grapes for making verjuice

Tacuinum Sanitatis![]() (1474)

(1474)

Paris Bibliothèque nationale

Verjuice (from Middle French vertjus "green juice") is a very acidic juice made by pressing unripe grapes. Sometimes lemon or sorrel juice, herbs or spices are added to change the flavour. In the Middle Ages, it was widely used all over Western Europe as an ingredient in sauces, as a condiment, or to deglaze preparations.

It was once used in many contexts where modern cooks would use either wine or some variety of vinegar, but has become much less widely used as wines and variously flavoured vinegars are more accessible nowadays. Nonetheless, it is still used in a number of French dishes as well as recipes from other European and Middle Eastern cuisines, and can be purchased at some gourmet grocery stores. The South Australian chef Maggie Beer has popularised the use of verjuice in her cooking, and it is being used increasingly in South Australian restaurants.

Modern cooks most often use verjuice in salad dressings as the acidic ingredient, when wine is going to be served with the salad. This is because verjuice provides a comparable sour taste component, yet without "competing with" (altering the taste of) the wine the way vinegar or lemon juice would.

The authors of The Medieval Kitchen: Recipes from France and Italy write that the grape seeds preserved in salts were also called verjus during the Middle Ages. In the regional French of Ardèche, a cider fermented from crab apple juice is called verjus.

Verjuice

By Franz Scheurer

Verjuice, by definition, is the acidic juice made from unripe fruit, primarily grapes. It can also be made from crab apples, unripe plums or gooseberries (in England a ‘fake’ verjuice was often made from mashed sorrel and water).

Its name derives from the French ‘vert’ (green) ‘jus’ (juice). As verjuice has traditionally been made from white and red grapes, leaving the juice on the skins long enough to colour it, the ‘vert’ refers to youth (unripe), rather than colour.

Verjuice is an ancient product dating back to medieval times, with culinary, practical and medicinal uses. According to French food historian, Jean Louis Flandrin, verjuice was used in 42% of all recipes in the early 15th century French cookbook ‘Viandier de Taillevent’. A 15th century English cookbook contains a recipe for spit roasted or grilled venison or beef using verjuice in the basting sauce; and the Franklin in one of Chaucer’s tales uses verjuice in a grandiose pie of chicken and turkey meat in puff pastry.

Verjuice combined with wine, lye or fuller’s earth was prized as a cleaning solution for furs and woollens, and verjuice mixed with sand was commonly used to clean rusty mail armour.As late as the 18th century the English still curdled blue (watered down) milk with verjuice to make a concoction drunk in the spring to prevent scurvy.

It fell from favour in the early 19th century (although its real demise may have started a lot earlier with the returning crusaders introducing lemons to Europe), to the extent where few people had even heard of it by the beginning of the 20th century. Starting in Europe, it is now undergoing a fashionable revival. Maggie Beer has been the driving force of verjuice’s revival in Australia and in her book ‘Cooking with Verjuice’ (ISBN: 0-14-300091-8) Maggie offers many tips and recipes from her own collection and from friends and colleagues, among them Stephanie Alexander, Stefano de Pieri, George Biron and Philip Johnson.The Italians call verjuice ‘agresto’ and in Spanish it is ‘argraz’ or ‘agrazada’. Never out of fashion in Iran, verjuice is called ‘abghooreh’; it is similarly popular with the Arabs who call it ‘hosrum’.

Think of verjuice as a gentle acidulant. It tastes tart, a bit like lemon juice or vinegar but not as harsh. It probably originated when vignerons thinned out the grapes to strengthen the vines and produce full flavoured fruit, and couldn’t bear to waste the unripe, pruned grapes. When this early crop of unripe berries is pressed, verjuice is obtained. In the Middle Ages bitter oranges were often used to make verjuice in Spain (keep in mind that the oranges of that era were considerably more tart and bitter than those we are used to today).

Verjuice is used fresh or fermented, and sometimes even undergoes a malo-lactic fermentation once bottled. This will only happen if malic acid and Bacillus gracilis bacterium are present. Malo-lactic fermentation converts malic acid into lactic acid and in the process improves the flavour. As it is commonly used for pickling, some medieval recipes for verjuice advocate the addition of salt to the juice, thereby preventing fermentation and also acting as a preservative. Due to modern (often pasteurised) verjuice’s relatively low acidity, it needs to be stored in the fridge once opened and should be used within a couple of weeks.

Uses

Instead of vinegar or lemon

juice in salad dressings;

Instead of white wine or brandy when deglazing pans;

Poaching fresh fruit or reconstituting dried fruit;

Drizzle over grilled fish or barbecued baby octopus;

Cutting the richness of sauces or meat dishes, especially with pork;

Instead of balsamic vinegar when caramelising onions;

Heavily reduced as a topping for ice cream;

In the preparation of mustards.

Making your own verjuice

As green grapes are almost impossible to buy use crab apples instead. Crush the crab apples (or process roughly in a food processor) place in a non-reactive container, add water to cover and seal with cheesecloth or muslin to keep out insects. Leave to ferment for 4 days in a warm place. Strain and squeeze the juice from the pulp. Strain a second time and bottle in sterilised jars or beer bottles and seal.