Lessico

Gregorio I

San Gregorio Magno

Papa, detto Magno, il Grande (Roma ca. 540-604). Nato dalla nobile famiglia Anicia, percorse la carriera politica e nel 573 era prefetto di Roma, carica che sostenne con dignità, sorretto da una solida preparazione culturale. Suo pensiero dominante però era ormai diventato il proposito di farsi monaco benedettino e di conseguenza rinunciò all'altissima carica e visse da monaco nella casa paterna trasformata in monastero (intitolato a Sant'Andrea), mentre fondava altri sei monasteri nelle sue proprietà terriere in Sicilia.

Nel 578 fu

ordinato diacono e invitato come apocrisario![]() a Costantinopoli, facendo una preziosa esperienza a contatto con la corte

imperiale e specialmente con l'imperatore Maurizio. Tornato a Roma nel 585,

riprese la vita monacale, approfondendo la conoscenza delle Sacre Scritture e

continuando il commento al libro di Giobbe, meglio conosciuto sotto il titolo

di Moralia.

a Costantinopoli, facendo una preziosa esperienza a contatto con la corte

imperiale e specialmente con l'imperatore Maurizio. Tornato a Roma nel 585,

riprese la vita monacale, approfondendo la conoscenza delle Sacre Scritture e

continuando il commento al libro di Giobbe, meglio conosciuto sotto il titolo

di Moralia.

Canto gregoriano

Pueri

Hebraeorum

portantes ramos olivarum

obviaverunt Domino

clamantes et dicentes

«Hosanna in excelsis»

Nel 590 Roma fu devastata da una grave pestilenza, che ebbe tra le sue numerosissime vittime anche papa Pelagio II. In questo stato di abbattimento e di angoscia i Romani elessero a una voce Gregorio papa e invano egli tentò di sottrarsi al ponderoso incarico anche appellandosi all'imperatore. Dopo la sua consacrazione, tuttavia, dedicò tutto se stesso al nuovo compito organizzando larghissimi soccorsi alla città, che appena uscita dalla pestilenza fu preda della fame, tenendo a freno gli indocili Longobardi, che premevano ai confini, organizzando l'amministrazione pubblica fino a renderla efficiente.

Nella cura delle anime esercitò un costante controllo sulla nomina dei vescovi in Italia; in Spagna rafforzò i diritti della Chiesa sui Visigoti convertiti di recente; in Africa si oppose al donatismo ed eliminò i gravi scandali che turbavano la vita cristiana; in Francia fece opera di pace fra le diverse fazioni che conducevano una feroce guerra civile; in Inghilterra accese la prima fiamma del cristianesimo; con l'Oriente tutta la sua abilità non riuscì a frenare i gravi contrasti esistenti, ma servì a non estenderne i dolorosi effetti.

Nell'azione politica Gregorio si sostituì al debole Esarcato di Ravenna nel trattare con i Longobardi e riuscì ad allontanarli da Roma; molto di più avrebbe ottenuto con i suoi buoni rapporti con la regina Teodolinda se non gli avesse fatto ostacolo l'ostinazione del governo bizantino.

Come scrittore Gregorio è fra i più fecondi e significativi del primo Medioevo: ricca e preziosa fonte d'informazione sono le sue Epistole (una raccolta di ben 854), scritte con stile semplice ma dignitoso, intuitivo ed efficace.

La Expositio in beatum Iob libri XXXV o Moralia si mantiene ferma ai tre significati delle Sacre Scritture, pur dando manifesta preferenza al significato morale tanto che nel Medioevo fu usata come manuale di vita morale.

La Regula pastoralis è una specie di esame di coscienza del pontificato di Gregorio visto alla luce del programma che si era prefisso all'inizio del suo ministero pontificale.

Le quaranta Homiliae in Evangelia e le ventidue Homiliae in Ezechielem costituiscono un'ideale continuazione dell'esegesi iniziata nei Moralia, mentre i Dialoghi dello stesso periodo (593-594) ebbero vastissima diffusione sia per la materia trattata (vita dei santi italiani e in particolare di San Benedetto) sia per lo stile facile, che li rendevano prontamente ricettivi al popolo. Festa il 12 marzo.

Apocrisario o apocrisiario

Dal greco apokrisiários, da apókrisis, risposta. In origine designava un funzionario della corte di Bisanzio, incaricato di portare i rescritti dell'imperatore nelle province. Successivamente con tale nome vennero distinti anche i rappresentanti fissi che i papi ebbero in Bisanzio, tra i secoli V e VIII, per tutelare i diritti della sede romana. Primo apocrisario fu Giuliano, vescovo di Coo, nominato da papa Leone Magno (morto a Roma nel 461).

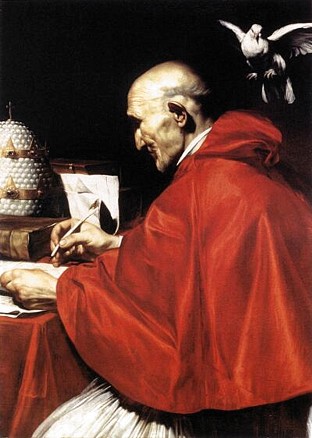

Papa Gregorio I

Gregorio

Magno - 1626/1627

Museo Provincial de Bellas Artes – Sevilla

Francisco de Zurbarán (1598-1664)

Gregorio I, detto Gregorio Magno (Roma, 540 circa – 12 marzo 604), fu il 64° papa della Chiesa cattolica e lo fu dal 3 settembre 590 alla sua morte. La Chiesa cattolica lo venera come santo e dottore della Chiesa.

Gregorio nacque verso il 540 dalla famiglia senatoriale degli Anici. Alcuni genealogisti collocano fra gli antenati di Gregorio i papi Felice III e Agapito I. Gregorio era figlio del senatore Gordiano e di Silvia. Alla morte del padre fu eletto, molto giovane, Prefetto di Roma. Grande ammiratore di Benedetto da Norcia, decise di trasformare i suoi possedimenti a Roma (sul Celio) e in Sicilia in altrettanti monasteri e di farsi monaco, quindi si dedicò con assiduità alla contemplazione dei misteri di Dio nella lettura della Bibbia. Non poté dimorare a lungo nel suo convento del Celio poiché papa Pelagio II lo inviò come nunzio presso la corte di Costantinopoli, dove restò per sei anni, e si guadagnò la stima dell'imperatore Maurizio I, di cui tenne a battesimo il figlio Teodosio.

Al suo rientro a Roma, nel 586, tornò nel monastero sul Celio, vi rimase però per pochissimo tempo, perché il 3 settembre 590 fu chiamato al soglio pontificio dall'entusiasmo dei credenti e dalle insistenze del clero e del senato di Roma, dopo la morte di Pelagio II di cui era stato segretario.

In quel tempo Roma era afflitta da una terribile pestilenza. Per implorare l'aiuto divino, Gregorio fece andare il popolo in processione per tre giorni consecutivi alla basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, cosa che, ovviamente, aumentò i contagi (ma allora non si sapeva). Cessata l'epidemia, più tardi una leggenda disse che durante la processione era apparso sulla mole Adriana l'arcangelo Michele che rimetteva la spada nel suo fodero come per annunziare che le preghiere dei fedeli erano state esaudite. Da allora la tomba di Adriano mutò il nome in quello di Castel Sant'Angelo, e una statua dell'angelo vi fu posta sulla cima.

Come papa si dimostrò uomo d'azione, pratico e intraprendente (chiamato "l'ultimo dei Romani"), nonostante fosse fisicamente abbastanza esile e cagionevole di salute. Fu amministratore energico, sia nelle questioni sociali e politiche per supportare i bisognosi di aiuto e protezione, sia nelle questioni interne della Chiesa. Trattò con molti paesi europei; con il re visigoto Recaredo di Spagna, convertitosi al Cattolicesimo, Gregorio fu in continui rapporti e fu in eccellente relazione con i re franchi. Con l'aiuto di questi e della regina Brunchilde riuscì a tradurre in realtà quello ch'era stato il suo sogno più bello: la conversione della Britannia, che affidò ad Agostino di Canterbury, priore del convento di Sant'Andrea.

A questo proposito si racconta che un giorno, scendendo dal suo convento sul Celio e vedendo sul mercato alcuni giovani schiavi britannici esposti per la vendita, bellissimi di aspetto e pagani, esclamasse rammaricato: « Non Angli, ma Angeli dovrebbero esser chiamati… »

In meno di due anni diecimila Angli, compreso Edelberto re del Kent, si convertirono. Era questo un grande successo di Gregorio, il primo della sua politica che mirava a eliminare gli avversari della Chiesa e ad accrescere l'autorità del papato con la conversione dei "barbari". Si dedicò anche ai problemi dell'Italia provata da alluvioni, carestie, pestilenze, amministrando la cosa pubblica con equità, supplendo all'incuria dei funzionari imperiali. Organizzò la difesa di Roma minacciata da Agilulfo, re dei Longobardi, coi quali poi riuscì a stabilire rapporti di buon vicinato e avviò la loro conversione. Ebbe cura degli acquedotti, favorì l'insediamento dei coloni eliminando ogni residuo di servitù della gleba. Riuscì a intrattenere epistole e rapporti amichevoli con il re della Barbagia, Ospitone, e cercò di dissuadere la popolazione dall'idolatria e dal paganesimo, convertendo Ospitone stesso al cristianesimo.

Riorganizzò a fondo la liturgia romana, ordinando le fonti liturgiche anteriori e componendo nuovi testi, e promosse quel canto tipicamente liturgico che dal suo nome si chiama gregoriano. L'epistolario (ci sono pervenute 848 lettere) e le omelie al popolo ci documentano ampiamente sulla sua molteplice attività e dimostrano la sua grande familiarità con la Sacra Scrittura. Morì il 12 marzo 604. Si può dire che sia stato il primo papa che mise il papato sulla via della potenza, il primo che utilizzò anche il potere temporale della Chiesa e, comunque, non dimenticò nella sua vita anche l'aspetto spirituale del suo compito.

Il canto gregoriano

Adoro

Te devote - di San Tommaso d'Aquino![]()

Il canto gregoriano è il canto rituale in lingua latina adottato dalla Chiesa Cattolica e prende il nome da Gregorio I. Mentre non si sa se abbia scritto egli stesso dei canti (i manoscritti più antichi contenenti i canti del repertorio gregoriano risalgono al IX secolo), la sua influenza sulla Chiesa fece sì che questi prendessero il suo nome.

A tal

proposito si cita la famosa leggenda di San Gregorio Magno, tramandata da un

intellettuale longobardo della corte di Carlo Magno (Paul Warnefried, detto

Paolo Diacono![]() ) e da un

gruppo di illustrazioni di vari manoscritti che vanno dal IX al XIII secolo:

Gregorio avrebbe dettato i suoi canti a un monaco, alternando tale dettatura a

lunghe pause; il monaco, incuriosito, avrebbe scostato un lembo del paravento

di stoffa che lo separava dal pontefice, per vedere cosa egli facesse durante

i lunghi silenzi, assistendo così al miracolo: una colomba (che rappresenta

naturalmente lo Spirito Santo), posata su una spalla del papa, gli stava a sua

volta dettando i canti all'orecchio.

) e da un

gruppo di illustrazioni di vari manoscritti che vanno dal IX al XIII secolo:

Gregorio avrebbe dettato i suoi canti a un monaco, alternando tale dettatura a

lunghe pause; il monaco, incuriosito, avrebbe scostato un lembo del paravento

di stoffa che lo separava dal pontefice, per vedere cosa egli facesse durante

i lunghi silenzi, assistendo così al miracolo: una colomba (che rappresenta

naturalmente lo Spirito Santo), posata su una spalla del papa, gli stava a sua

volta dettando i canti all'orecchio.

Opere di Gregorio I

Sermoni (40 sui Vangeli sono riconosciuti come autentici, 22 su Ezechiele, 2 sul Cantico dei cantici)

Dialoghi - sulla vita di san Benedetto da Norcia

Moralia in Iob

Le regole per i pastori

Circa 850 lettere sono sopravvissute dal suo Registro papale delle lettere (Registrum Gregorii). Questa collezione serve come inestimabile fonte primaria su quegli anni.

Opera Omnia dal Migne Patrologia Latina con indici analitici.

Il mito dell'incesto

Una storia circa le sue origini, probabilmente apocrifa, vuole che i suoi parenti biologici fossero gemelli di nobile nascita, che commisero incesto su istigazione del diavolo. Ancora neonato venne affidato al mare dalla madre, che lo aveva posto all'interno di una cesta. Venne quindi trovato e allevato da un pescatore. All'età di sei anni entrò in un convento, che successivamente lasciò per inseguire una carriera da cavaliere. Viaggiò fino alla sua terra d'origine, dove sposò la regina del luogo, che era, a sua insaputa, sua madre. Dopo aver scoperto questo doppio incesto, spese diciassette anni nel pentimento prima di essere, infine, eletto papa. Questo mito ha ispirato il romanzo Der Erwählte ("L'eletto") di Thomas Mann.

Pope Saint Gregory I or Gregory the Great (c. 540 – 12 March 604) was pope from 3 September 590 until his death. He is also known as Gregory the Dialogist in Eastern Orthodoxy because of his Dialogues. For this reason, English translations of Orthodox texts will sometimes list him as "Gregory Dialogus". He was the first of the popes to come from a monastic background. Gregory is a Doctor of the Church and one of the six Latin Fathers. Immediately after his death, Gregory was canonized by popular acclaim. He is seen as a patron of England for having sent Augustine of Canterbury there on mission.

Early life

The exact date of St. Gregory's birth is uncertain, but is usually estimated to be around the year 540, in the city of Rome. His parents named him Gregorius, which according to Aelfric in "An Homily on the Birth-Day of S. Gregory," translated by Elizabeth Elstob, "... is a Greek Name, which signifies in the Latin Tongue Vigilantius, that is in English, Watchful...." The medieval writers who give this universally believed etymology do not hesitate to apply it to the life of Gregory. Aelfric, for example, goes on: "He was very diligent in God's Commandments."

When Gregory was a child, Italy was retaken from the Goths by Justinian I, emperor of the Roman Empire ruling from Constantinople. The war was over by 552. An invasion of the Franks was defeated in 554. The western empire had long since vanished in favor of the Gothic kings of Italy. The senate had been disbanded. After 554 there was peace in Italy and the appearance of restoration, except that the government now resided in Constantinople. Italy was still united into one country, "Rome" and still shared a common official language, the very last of classical Latin.

As the fighting had been mainly in the north, the young Gregorius probably saw little of it. Totila sacked and vacated Rome in 547, destroying most of its ancient population, but in 549 he invited those who were still alive to return to the empty and ruinous streets. It has been hypothesized that young Gregory and his parents, Gordianus and Silvia, retired during that intermission to Gordianus' Sicilian estates, to return in 549.

Gregory had been born into a wealthy noble Roman family with close connections to the church. The Lives in Latin use nobilis but they do not specify from what historical layer the term derives or identify the family. No connection to patrician families of the Roman Republic has been demonstrated. Gregory's great-great-grandfather had been Pope Felix III, but that pope was the nominee of the Gothic king, Theodoric.

The family owned and resided in a villa suburbana on the Caelian Hill, fronting the same street, now the Via di San Gregorio, as the former palaces of the Roman emperors on the Palatine Hill opposite. The north of the street runs into the Colosseum; the south, the Circus Maximus. In Gregory's day the ancient buildings were in ruins and were privately owned. Villas covered the area. Gregory's family also owned working estates in Sicily and around Rome.

Gregory's father, Gordianus, held the position of Regionarius in the Roman Church. Nothing further is known about the position. Gregory's mother, Silvia, was well-born and had a married sister, Pateria, in Sicily. Gregory later had portraits done in fresco in their former home on the Caelian and these were described 300 years later by John the Deacon. Gordianus was tall with a long face and light eyes. He wore a beard. Silvia was tall, had a round face, blue eyes and a cheerful look. They had another son, name and fate unknown.

The monks of St. Andrew's (the ancestral home on the Caelian) had a portrait of Gregory made after his death, which John the Deacon also saw in the 9th century. He reports the picture of a man who was "rather bald" and had a "tawny" beard like his father's and a face that was intermediate in shape between his mother's and father's. The hair that he had on the sides was long and carefully curled. His nose was "thin and straight" and "slightly aquiline." "His forehead was high." He had thick, "subdivided" lips and a chin "of a comely prominence" and "beautiful hands."

Gregory was educated. Gregory of Tours reports that "in grammar, dialectic and rhetoric ... he was second to none...." He wrote correct Latin but did not read or write Greek. He knew Latin authors, natural science, history, mathematics and music and had such a "fluency with imperial law" that he may have trained in law, it has been suggested, "as a preparation for a career in public life." While his father lived, Gregory took part in Roman political life and at one point was Prefect of the City.

Gregory as monastic

Gregory's father's three sisters were nuns. Gregory's mother Silvia herself is a saint. On his father's death, he converted his family villa suburbana, located on the Caelian Hill just opposite the Circus Maximus, into a monastery dedicated to the apostle Saint Andrew. Gregory himself entered as a monk. After his death it was rededicated as San Gregorio Magno al Celio.

Eventually, Pope Pelagius II ordained him a deacon and solicited his help in trying to heal the schism of the Three Chapters in northern Italy. In 579, Pelagius II chose Gregory as his apocrisiarius or ambassador to the imperial court in Constantinople. On his return to Rome, Gregory served as secretary to Pelagius II, and was elected Pope to succeed him.

Gregory as Pope

When he became Pope in 590, among his first acts were writing a series of letters disavowing any ambition to the throne of Peter and praising the contemplative life of the monks. At that time the Holy See had not exerted effective leadership in the West since the pontificate of Gelasius I. The episcopacy in Gaul was drawn from the great territorial families, and identified with them: the parochial horizon of Gregory's contemporary, Gregory of Tours, may be considered typical; in Visigothic Spain the bishops had little contact with Rome; in Italy the papacy was beset by the violent Lombard dukes and the rivalry of the Jews in the Exarchate of Ravenna and in the south. The scholarship and culture of Celtic Christianity had developed utterly unconnected with Rome, and it was from Ireland that Britain and Germany were likely to become Christianized, or so it seemed.

Gregory is credited with re-energizing the Church's missionary work among the barbarian peoples of northern Europe. He is most famous for sending a mission under Augustine of Canterbury to evangelize the pagan Anglo-Saxons of England. The mission was successful, and it was from England that missionaries later set out for the Netherlands and Germany.

Servus servorum Dei

In line with his predecessors such as Dionysius, Damasus, and St. Leo the Great, St. Gregory asserted the primacy of the office of the Bishop of Rome. Although he did not employ the term "Pope", he summed up the responsibilities of the papacy in his official appellation, as "servant of the servants of God". As Benedict of Nursia had justified the absolute authority of the abbot over the souls in his charge, so Gregory expressed the hieratic principle that he was responsible directly to God for his ministry.

St. Gregory's pontificate saw the development of the notion of private penance as parallel to the institution of public penance. He explicitly taught a doctrine of Purgatory where a soul destined to undergo purification after death because of certain sins, could begin its purification in this earthly life, through good works, obedience and Christian conduct, making the travails to come lighter and shorter.

St. Gregory's relations with the Emperor in the East were a cautious diplomatic stand-off. He concentrated his energies in the West, where many of his letters are concerned with the management of papal estates. His relations with the Merovingian kings, encapsulated in his deferential correspondence with Childebert II, laid the foundations for the papal alliance with the Franks that would transform the Germanic kingship into an agency for the Christianization of the heart of Europe — consequences that remained in the future.

More immediately, Gregory undertook the conversion of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, where inaction might have encouraged the Celtic missionaries already active in the north of Britain. Sending Augustine of Canterbury to convert the Kingdom of Kent was prepared by the marriage of the king to a Merovingian princess who had brought her chaplains with her. By the time of Gregory's death, the conversion of the king and the Kentish nobles and the establishment of a Christian toehold at Canterbury were established.

St. Gregory's chief acts as Pope include his long letter issued in the matter of the schism of the Three Chapters of the bishops of Venetia and Istria. He is also known in the East as a tireless worker for communication and understanding between East and West. He is also credited with increasing the power of the papacy. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, he was declared a saint immediately after his death by "popular acclamation".

Liturgical reforms

In letters, St. Gregory remarks that he moved the Pater Noster (Our Father) to immediately after the Roman Canon and immediately before the Fraction. This position is still maintained today in the Roman Liturgy. The pre-Gregorian position is evident in the Ambrosian Rite. Gregory added material to the Hanc Igitur of the Roman Canon and established the nine Kyries (a vestigial remnant of the litany which was originally at that place) at the beginning of Mass. He also reduced the role of deacons in the Roman Liturgy.

Sacramentaries directly influenced by Gregorian reforms are referred to as Sacrementaria Gregoriana. With the appearance of these sacramentaries, the Western liturgy begins to show a characteristic that distinguishes it from Eastern liturgical traditions. In contrast to the mostly invariable Eastern liturgical texts, Roman and other Western liturgies since this era have a number of prayers that change to reflect the feast or liturgical season; These variations are visible in the collects and prefaces as well as in the Roman Canon itself.

A system of writing down reminders of chant melodies was probably devised by monks around 800 to aid in unifying the church service throughout the Frankish empire. Charlemagne brought cantors from the Papal chapel in Rome to instruct his clerics in the “authentic” liturgy. A program of propaganda spread the idea that the chant used in Rome came directly from Gregory the Great, who had died two centuries earlier and was universally venerated. Pictures were made to depict the dove of the Holy Spirit perched on Gregory's shoulder, singing God's authentic form of chant into his ear. This gave rise to calling the music "Gregorian chant". A more accurate term is plainsong or plainchant.

Sometimes the establishment of the Gregorian Calendar is erroneously attributed to Gregory the Great; however, that calendar was actually instituted by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 by way of a papal bull entitled, Inter gravissimas.

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, Gregory is credited with compiling the Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts. This liturgy is celebrated on Wednesdays, Fridays, and certain other weekdays during Great Lent in the Eastern Orthodox Church and those Eastern Catholic Churches which follow the Byzantine Rite.

Writings

Gregory is the only Pope between the fifth and the eleventh centuries whose correspondence and writings have survived enough to form a comprehensive corpus. Some of his writings are:

Sermons (forty on the Gospels are recognized as authentic, twenty-two on Ezekiel, two on the Song of Songs)

Dialogues, a collection of often fanciful narratives including a popular life of Saint Benedict

Commentary on Job, frequently known even in English-language histories by its Latin title, Magna Moralia

The Rule for Pastors, in which he contrasted the role of bishops as pastors of their flock with their position as nobles of the church: the definitive statement of the nature of the episcopal office

Copies of some 854 letters have survived, out of an unknown original number recorded in Gregory's time in a register. It is known to have existed in the Vatican, its last known location, in the 9th century. It consisted of 14 papyrus rolls, now missing. Copies of letters had begun to be made, the largest batch of 686 by order of Adrian I. The majority of the copies, dating from the 10th to the 15th century, are stored in the Vatican Library.

Opinions of the writings of Gregory vary. "His character strikes us as an ambiguous and enigmatic one," Cantor observed. "On the one hand he was an able and determined administrator, a skilled and clever diplomat, a leader of the greatest sophistication and vision; but on the other hand, he appears in his writings as a superstitious and credulous monk, hostile to learning, crudely limited as a theologian, and excessively devoted to saints, miracles, and relics".

Controversy with Eutychius

In Constantinople, Gregory took issue with the aged Patriarch Eutychius of Constantinople, who had recently published a treatise, now lost, on the General Resurrection. Eutychius maintained that the resurrected body "will be more subtle than air, and no longer palpable".Gregory opposed with the palpability of the risen Christ in Luke 24:39. As the dispute could not be settled, the Roman emperor, Tiberius II Constantine, undertook to arbitrate. He decided in favor of palpability and ordered Eutychius' book to be burned. Shortly after both Gregory and Eutychius became ill, Gregory recovered, but Eutychius died on April 5, 582, at age 70. On his deathbed he recanted inpalpability and Gregory dropped the matter. Tiberius also died a few months after Eutychius.

Sermon on Mary Magdalene

In a sermon whose text is given in Patrologia Latina, Gregory stated that he believed "that the woman Luke called a sinner and John called Mary was the Mary out of whom Mark declared that seven demons were cast" (Hanc vero quam Lucas peccatricem mulierem, Joannes Mariam nominat, illam esse Mariam credimus de qua Marcus septem damonia ejecta fuisse testatur), thus identifying the sinner of Luke 7:37, the Mary of John 11:2 and 12:3 (the sister of Lazarus and Martha of Bethany), and Mary Magdalene, from whom Jesus had cast out seven demons, related in Mark 16:9.

While most Western writers shared this view, it was not seen as a Church teaching, but as an opinion, the pros and cons of which were discussed. With the liturgical changes made in 1969, there is no longer mention of Mary Magdalene as a sinner in Roman Catholic liturgical materials. The Eastern Orthodox Church has never accepted Gregory's identification of Mary Magdalene with the sinful woman.

Iconography

Gregory

I – ca. 1610

by Carlo Saraceni

told Carlo Veneziano (ca.1579-1620)

In art Gregory is usually shown in full pontifical robes with the tiara and double cross, despite his actual habit of dress. Earlier depictions are more likely to show a monastic tonsure and plainer dress. Orthodox icons traditionally show St. Gregory vested as a bishop, holding a Gospel Book and blessing with his right hand. It is recorded that he permitted his depiction with a square halo, then used for the living. A dove is his attribute, from the well-known story recorded by his friend Peter the Deacon, who tells that when the pope was dictating his homilies on Ezechiel a curtain was drawn between his secretary and himself. As, however, the pope remained silent for long periods at a time, the servant made a hole in the curtain and, looking through, beheld a dove seated upon Gregory's head with its beak between his lips. When the dove withdrew its beak the pope spoke and the secretary took down his words; but when he became silent the servant again applied his eye to the hole and saw the dove had replaced its beak between his lips.

Gregory being inspired to write. This scene is shown as a version of the traditional Evangelist portrait (where the Evangelists' symbols are also sometimes shown dictating) from the tenth century onwards. An early example is the dedication miniature from the an eleventh century manuscript of St. Gregory's Moralia in Job. The miniature shows the scribe, Bebo of Seeon Abbey, presenting the manuscript to the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry II. In the upper left the author is seen writing the text under divine inspiration Usually the dove is shown whispering in Gregory's ear for a clearer composition.

The imaginative and anachronistic example at the top of this article is from the studio of Carlo Saraceni or by a close follower, ca 1610. From the Giustiniani collection, the painting is conserved in the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Rome. The face of Gregory is a caricature of the features described by John the Deacon mentioned under his early life above: total baldness, outthrust chin, beak-like nose, where John had described partial baldness, a mildly protruding chin, slightly aquiline nose and strikingly good looks. In this picture also Gregory has his monastic back on the world, which the real Gregory, despite his reclusive intent, was seldom allowed to have.

Alms

Alms in Christianity is defined by passages of the New Testament such as Matthew 19:21, which commands "...go and sell that thou hast, and give to the poor ... and come and follow me." A donation on the other hand is a gift to some sort of enterprise, profit or non-profit. On the one hand the the alms of St. Gregory are to be distinguished from his donations, but on the other he probably saw no such distinction. The church had no interest in secular profit and as pope Gregory did his utmost to encourage that high standard among church personnel. Apart from maintaining its facilities and supporting its personnel the church gave most of the donations it received as alms.

Gregory is known for his administrative system of charitable relief of the poor at Rome. They were predominantly refugees from the incursions of the Lombards. The philosophy under which he devised this system is that the wealth belonged to the poor and the church was only its steward. He received lavish donations from the wealthy families of Rome, who, following his own example, were eager to expiate to God for their sins. He gave alms equally as lavishly both individually and en masse. He wrote in letters: "I have frequently charged you ... to act as my representative ... to relieve the poor in their distress ...." - "... I hold the office of steward to the property of the poor ...."

The church received donations of many different kinds of property: consumables such as food and clothing; investment property: real estate and works of art; and capital goods, or revenue-generating property, such as the Sicilian latifundia, or agricultural estates, staffed and operated by slaves, donated by Gregory and his family. The church already had a system for circulating the consumables to the poor: associated with each parish was a diaconium or office of the deacon. He was given a building from which the poor could at any time apply for assistance.

The state in which Gregory became pope in 590 was a ruined one. The Lombards held the better part of Italy. Their predations had brought the economy to a standstill. They camped nearly at the gates of Rome. The city was packed with refugees from all walks of life, who lived in the streets and had few of the necessities of life. The seat of government was far from Rome in Constantinople, which appeared unable to undertake the relief of Italy. The pope had sent emissaries, including Gregory, asking for assistance, to no avail.

In 590 Gregory could wait for Constantinople no longer. He organized the resources of the church into an administration for general relief. In doing so he evidenced a talent for and intuitive understanding of the principles of accounting, which was not to be invented for centuries. The church already had basic accounting documents: every expense was recorded in journals called regesta, "lists" of amounts, recipients and circumstances. Revenue was recorded in polyptici, "books." Many of these polyptici were ledgers recording the operating expenses of the church and the assets, the patrimonia. A central papal administration, the notarii, under a chief, the primicerius notariorum, kept the ledgers and issued brevia patrimonii, or lists of property for which each rector was responsible.

Gregory began by aggressively requiring his churchmen to seek out and relieve needy persons and reprimanded them if they did not. In a letter to a subordinate in Sicily he wrote: "I asked you most of all to take care of the poor. And if you knew of people in poverty, you should have pointed them out ... I desire that you give the woman, Pateria, forty soldi for the childrens' shoes and forty bushels of grain ...." Soon he was replacing administrators who would not cooperate with those who would and at the same time adding more in a build-up to a great plan that he had in mind. He understood that expenses must be matched by income. To pay for his increased expenses he liquidated the investment property and paid the expenses in cash according to a budget recorded in the polyptici. The churchmen were paid four times a year and also personally given a golden coin for their trouble.

Money, however, was no substitute for food in a city that was on the brink of famine. Even the wealthy were going hungry in their villas. The church now owned between 1300 and 1800 square miles of revenue-generating farmland divided into large sections called patrimonia. It produced goods of all kinds, which were sold, but Gregory intervened and had the goods shipped to Rome for distribution in the diaconia. He gave orders to step up production, set quotas and put an administrative structure in place to carry it out. At the bottom was the rusticus who produced the goods. Some rustici were or owned slaves. He turned over part of his produce to a conductor from whom he leased the land. The latter reported to an actionarius, the latter to a defensor and the latter to a rector. Grain, wine, cheese, meat, fish and oil began to arrive at Rome in large quantities, where it was given away for nothing as alms.

Distributions to qualified persons were monthly. However, a certain proportion of the population lived in the streets or were too ill or infirm to pick up their monthly food supply. To them Gregory sent out a small army of charitable persons, mainly monks, every morning with prepared food. It is said that he would not dine until the indigent were fed. When he did dine he shared the family table, which he had saved (and which still exists), with 12 indigent guests. To the needy living in wealthy homes he sent meals he had cooked with his own hands as gifts to spare them the indignity of receiving charity. Hearing of the death of an indigent in a back room he was depressed for days, entertaining for a time the conceit that he had failed in his duty and was a murderer.

These and other good deeds and charitable frame of mind completely won the hearts and minds of the Roman people. They now looked to the papacy for government, ignoring the rump state at Constantinople, which had only disrespect for Gregory, calling him a fool for his pacifist dealings with the Lombards. The office of urban prefect went without candidates. From the time of Gregory the Great to the rise of Italian nationalism the papacy was most influential in ruling Italy.

Famous quotes and anecdotes

Non Angli, sed Angeli - "They are not Angles, but Angels". Aphorism of unknown origin summarizing words reported to have been spoken by Gregory when he first encountered blue-eyed, blond-haired English boys at a slave market, sparking his dispatching of St. Augustine of Canterbury to England to convert the English, according to Bede. He said: "Well named, for they have angelic faces and ought to be co-heirs with the angels in heaven." Discovering that their province was Deira, he went on to add that they would be rescued de ira, "from the wrath", and that their king was named Aella, Alleluia, he said.

Ecce locusta - "Look at the locust." Gregory himself wanted to go to England as a missionary and started out for there. On the fourth day as they stopped for lunch a locust landed on the edge of the Bible Gregory was reading. He exclaimed ecce locusta, "look at the locust", but reflecting on it he saw it as a sign from Heaven since the similar sounding loco sta means "stay in place." Within the hour an emissary of the pope arrived to recall him.

Pro cuius amore in eius eloquio nec mihi parco - "For the love of whom (God) I do not spare myself from his Word." The sense is that since the creator of the human race and redeemer of him unworthy gave him the power of the tongue so that he could witness, what kind of a witness would he be if he did not use it but preferred to speak infirmly?

Non enim pro locis res, sed pro bonis rebus loca amanda sunt - "Things are not to be loved for the sake of a place, but places are to be loved for the sake of their good things." When Augustine asked whether to use Roman or Gallican customs in the mass in England, Gregory said, in paraphrase, that it was not the place that imparted goodness but good things that graced the place, and it was more important to be pleasing to the Almighty. They should pick out what was "pia", "religiosa" and "recta" from any church whatever and set that down before the English minds as practice.

Feast Day

The current Roman Catholic calendar of saints, revised in 1969 as instructed by the Second Vatican Council, celebrates St. Gregory the Great on 3 September. Before that, the General Roman Calendar assigned his feast day to 12 March, the day of his death in 604. This day always falls within Lent, during which there are no obligatory Memorials. For this reason his feast day was moved to 3 September the day of his episcopal consecration in 590.

The Eastern Orthodox Church and the associated Eastern Catholic Churches continue to commemorate St. Gregory on 12 March. The occurrence of this date during Great Lent is considered appropriate in the Byzantine Rite, which traditionally associates Saint Gregory with the Divine Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts, celebrated only during that liturgical season.

Other Churches too honour Saint Gregory: the Church of England on 3 September, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and the Episcopal Church in the United States on 12 March. A traditional procession is held in Zejtun, Malta in honour of Saint Gregory (San Girgor) on Easter Wednesday, which most often falls in April, the range of possible dates being 25 March to 28 April.

Grégoire Ier, dit le Grand ou le Dialogue (né vers 540, mort le 12 mars 604), devient pape en 590. Docteur de l'Église, il est l'un des quatre Pères de l'Église d'Occident, avec saint Ambroise, saint Augustin et saint Jérôme. Son influence durant le Moyen Âge fut considérable. Saint Grégoire est très présent dans l'iconographie des manuscrits et des monuments figurés, où il est, avec saint Pierre, le pape par excellence. Il est souvent représenté en train de recevoir l'inspiration d'une colombe. Il est fêté le 12 mars.

Débuts

Il naquit à Rome vers 540, d'une famille chrétienne et patricienne, de la branche Anicia. Son père, le sénateur Gordien, est administrateur d'un des sept arrondissements de Rome. Deux de ses sœurs sont honorées saintes (Tharsilla et Aemiliane), et il avait parmi ses ancêtres le pape Félix III. Sa mère, Sylvie, est elle aussi honorée sainte. Il est éduqué dans le climat de renouveau culturel suscité en Italie par la Pragmatica sanctio, et excelle, «selon le témoignage de Grégoire de Tours, dans l'étude de la grammaire, de la dialectique et de la rhétorique. En 572, il est nommé préfet de la ville, ce qui lui permet de s'initier à l'administration publique, et devient ainsi le premier magistrat de Rome. Il utilise ses aptitudes pour réorganiser le patrimoine de Saint-Pierre. En 574, il souscrit à l'acte par lequel Laurent, évêque de Milan, reconnaît la condamnation des «Trois Chapitres» par le IIe Concile de Constantinople de 553.

Vers 574-575, il adopte la vie monastique et transforme en monastère dédié à saint André la demeure familiale située sur le mont Cælius. Il nomme pour abbé le moine Valentien. On ne sait pas si Grégoire assuma personnellement la direction de la communauté. Ayant hérité de grandes richesses à la mort de son père, il fonde aussi 6 monastères en Sicile. On ne sait pas si Grégoire et ses moines adoptèrent la règle de saint Benoît, mais « on ne saurait cependant douter de l'harmonie fondamentale existant entre l'idéal monastique de Benoît et celle du grand pontife.

À Constantinople

Grégoire est ordonné diacre par le pape Pélage II (ou peut-être par Benoît Ier, mais c'est moins probable) avant d'être envoyé à Constantinople comme apocrisiaire (ambassadeur permanent, ou nonce). Il s'y rend accompagné de quelques frères, et y résidera jusqu'à la fin de 585 ou le début de 586, « sans songer, d'ailleurs, à apprendre le grec ni à s'initier à la théologie orientale. Cela montre combien le fossé entre la culture orientale et latine de la chrétienté est déjà grand. C'est là qu'il rédigea sa plus importante œuvre exégétique, l'Expositio in Job. Il se fit aussi remarquer par une controverse avec Eutychius, le Patriarche de Constantinople, à propos de la résurrection des corps. En effet, Grégoire défendait la thèse traditionnelle de l'Église sur la résurrection des corps, tandis qu'Eutychius «appliquait au dogme catholique le principe de l'hylémorphisme aristotélicien.

À la demande du pape, Grégoire attira aussi l'attention de l'empereur Maurice à propos de l'invasion lombarde en Italie. De retour à Rome, il reprit la vie monastique. Il joua aussi le rôle de secrétaire et conseiller de Pélage II. À ce titre, il rédige l'Épître III de Pélage, où il soutient la légitimité de la condamnation des Trois Chapitres par le concile de Constantinople de 553. Le pape meurt de la peste le 7 février 590. Grégoire « est élu pape par l'acclamation unanime du clergé et du peuple ». Il essaie de se dérober, faisant même appel à l'empereur, mais c'est en vain. Il est consacré pape à Saint-Pierre, le 3 septembre 590. Cet épisode est raconté dans la Légende dorée.

Pape

Le pontificat de Grégoire Ier se déroule dans un contexte fort difficile. La ville est ravagée par la peste, le Tibre déborde. Il doit donc à la fois veiller à rassurer les fidèles (certains croient que la fin du monde est arrivée) et utiliser ses talents d'administrateur pour veiller au ravitaillement de la ville. Dans l'ensemble de son pontificat, on notera une importante réforme administrative à l'avantage des populations de campagne, ainsi que la restructuration du patrimoine de toutes les églises d'Occident, afin d'en faire « des témoins de la pauvreté évangélique et des instruments de défense et de protection du monde agricole contre toute forme d'injustice publique ou privée.

Durant son pontificat, Grégoire adopte une « attitude d'attente et de négociation avec les Lombards ». Non satisfait des mesures prises par l'empereur Maurice («J'attends plus de la miséricorde de Jésus de qui vient la justice que de votre piété.» écrit-il à l'empereur), il prend lui-même les choses en main, en signant en 595 une trêve avec Agilulf. En 598, il favorise une nouvelle trêve, entre l'exarque Callinicus et le roi lombard. Maurice trouve ce comportement «prétentieux». Grégoire se défend en argumentant: « Si j'avais voulu me prêter à la destruction des Lombards lorsque j'étais apocrisiaire à Constantinople, ce peuple n'aurait plus aujourd'hui ni roi, ni comtes; il serait en proie à une irrémédiable confusion; mais, comme je crains Dieu, je n'ai voulu me prêter à la perte de qui que ce soit. » Grâce à ses contacts avec Théodelinde, la reine franque des Lombards, un mouvement progressif de conversions s'amorça parmi ceux-ci.

Le geste le plus important de Grégoire Ier par rapport à l'évangélisation est l'envoi en mission, en 596, de saint Augustin de Cantorbéry, accompagné de quarante moines du monastère du mont Cælius, afin de restaurer le christianisme en Grande-Bretagne. En effet, sous l’empire, la Bretagne avait été quelque peu christianisée, mais les Saxons avaient envahi l’île et repoussé vers l’ouest les chrétiens bretons. Grégoire fait aussi acheter de jeunes esclaves anglais pour les faire élever dans des monastères. Le grand historien Edward Gibbon dira: « César avait eu besoin de six légions pour conquérir la Grande-Bretagne. Grégoire y réussit avec quarante moines » Dans une lettre adressée à un missionnaire en partance pour la Grande-Bretagne païenne, en 601, Grégoire Ier donnait cet ordre: « Les temples abritant les idoles dudit pays ne seront pas détruits; seules les idoles se trouvant à l’intérieur le seront [...]. Si lesdits temples sont en bon état, il conviendra de remplacer le culte des démons par le service du vrai Dieu.» Augustin devint le premier archevêque de Cantorbéry.

Grégoire Ier mourut le 12 mars 604 et fut inhumé au niveau du portique de l'Église Saint-Pierre de Rome. Cinquante ans plus tard, ses restes furent transférés sous un autel, qui lui fut dédié, à l'intérieur de la basilique, ce qui officialisa sa sainteté.

Correspondance

Le Registrum epistolarum est composé de 814 lettres réparties en 14 livres, qui correspondent aux années du pontificat grégorien (590-604). C'est une composition assez hétéroclite: lettres spirituelles, lettres officielles à lire en public, ordonnances portant sur des questions de gouvernement, formulaires de nomination et de confirmation de charges, formulaires d'autorisation et de privilège... Cependant, certaines lettres permettent de tracer un portrait assez riche et précis du monde rural de la fin du VIe siècle.

Commentaires et homélies

L'Expositio in Job ou Moralia in Job (morales sur Job) est son œuvre exégétique la plus importante. Commencée à Constantinople, d'abord sous forme d'entretiens destinés aux frères de sa communauté, puis poursuivie sous forme de dictée, elle fut réorganisée et achevée à Rome, vers 595. Elle comporte 35 livres. «Par une œuvre qui est plus une catéchèse biblique qu'une construction scientifique, il a tracé les lignes essentielles de la théologie morale classique.».

Homiliæ in Evangelium est un recueil de 40 homélies reproduisant sa prédication durant les 2 premières années de son pontificat. «Elles constituent un modèle de prédication populaire, remplie d'enseignement moral et mystique exposé sous une forme simple et naturelle, renforcé souvent par des exemples s'adressant à la grande masse des fidèles.» P. Batiffol les considère comme «des modèles de l'éloquence pastorale et la prédication liturgique.

Homeliæ in Hiezechihelem sont 22 homélies sur le livre d'Ézéchiel, rédigées vers 593–594, alors qu'Agilulf menace d'assiéger Rome. Elles sont d'un niveau plus élevé que les homélies sur l'évangile. Le premier livre, dédié à Marinien de Syracuse, traite du charisme prophétique. Il s'adresse principalement aux prédicateurs et aux évêques. Le second livre, qui s'adresse aux moines de Caelius, commente la structure du Temple de Jérusalem. Par la symbolique des nombres, il explique la voie d'accès au silence contemplatif.

Plusieurs autres écrits n'ont pas été rédigés directement de la main de Grégoire. Ainsi, Expositiones in Canticum Canticorum, concernant les 8 premiers verset du texte du Cantique des cantiques, et in librum primum Regum, qui commente 1S 1-16, sont deux textes qui ont été dictés de mémoire par le moine Claude, d'après ce qu'il avait entendu de Grégoire. D'autres commentaires, sur les proverbes, les prophètes, l'Heptateuque, ont été rédigés de la même manière. Ces écrits sont malheureusement perdus aujourd'hui.

Autres écrits

La réforme liturgique de Grégoire est décrite dans le livre des sacrements. «Il rassembla en un seul livre le Codex de Gélase concernant la liturgie de la messe. Il y retrancha beaucoup de choses, en modifia quelques-unes et en ajouta certaines. Il institua ce livre: Livre des sacrements.» Nous ne possédons cependant pas la version originale. Celle que l'on a actuellement est le texte envoyé par Adrien Ier à Charlemagne, vers 785-786, et contient plusieurs enrichissements reflétant des ajouts faits entre temps à la pratique liturgique usuelle. La tradition attribue aussi à Grégoire un Antiphonarium.

La Regula pastoralis est adressée à Jean de Ravenne. «Dans la Règle, divisée en quatre parties, Grégoire justifie ses réticences à assumer la charge pastorale, et il met en lumière l'élévation de la dignité épiscopale; il souligne les versus de pasteur.» (p. 1105) La troisième partie décrit de quelle manière on doit éduquer les différentes catégories de fidèles. La Règle exhorte l'évêque à un renouvellement personnel continu, afin que sa parole soit toujours incisive et efficace. L'ouvrage est traduit en grec dès 602 et sert de livre de base de la formation du clergé au Moyen Âge. Il demeure un classique de la vie spirituelle.

Les Dialogues témoignent de la sainteté d'évêques, moines, prêtres et gens du peuple, contemporains à Grégoire. Ils relatent des miracles opérés par de saints personnages en Italie. Le second livre constitue la principale source biographique que l'on a sur Benoît de Nursie. Le quatrième livre évoque des manifestations extraordinaires démontrant l'immortalité de l'âme humaine, conséquence d'une légende hagiographique racontant comment il composa les propres de la Messe. Influence sur la théologie.

Grégoire propose la mise en place d'une pédagogie chrétienne «où la formation grammaticale, dialectique et rhétorique se baserait, non plus sur des textes profanes, comme cela se faisait encore de son temps, mais sur des textes sacrés. Cette voie sera par la suite suivie par d'autres, notamment Isidore de Séville, Julien II de Tolède et Bède. Ses ouvrages théologiques resteront, jusqu'à la fin du Moyen Âge, l'une des autorités les plus souvent citées dans la prédication et l'enseignement, où il prend place après saint Augustin d'Hippone, dont il simplifie parfois la pensée, non sans l'enrichir d'autre part en l'adaptant à la mentalité des temps nouveaux. Il n'est cependant pas un théologien original, en ce sens qu'il reprend surtout la doctrine commune. C'est que l'époque des grandes controverses dogmatique est passée. «Il reprend l'enseignement d'Augustin sur la grâce, la prédestination, le sort des enfants morts sans baptême;il reprend et précise la catéchèse traditionnelle sur les sacrements, la discipline pénitentielle, les bonnes œuvres, le culte des saints.»

D'un point de vue exégétique, il utilise les procédés de la rhétorique classique. Bien qu'il ne néglige pas le sens littéral de l'Écriture, il le dépasse pour s'élever à l'allégorie. Ainsi, dans son homélie sur Ézéchiel, il s'attarde principalement sur la cause ou l'hypothèse dont l'objet sont les personnes ou les faits historiques. Il ne parle pas de la prophétie, mais du prophète. En général, dans son discours, «les antinomies se résolvent grâce à l'unité qui permet de dire que l'Église est à la fois visible et invisible, humaine et divine, active et contemplative, présente dans le monde et plongée dans la réalité future. Mais Grégoire est avant tout un moraliste. «Par une œuvre qui est plus une catéchèse biblique qu'une construction scientifique, il a tracé les lignes essentielles de la théologie morale classique.» D'ailleurs, le fait que l'Expositio in Job ait reçu, de son vivant, le titre de Moralia in Job en témoigne. On lui doit, dans un tableau large et divers de la morale chrétienne et des finalités de la vie mystique, une approche assez humaniste de l'équilibre personnel que le chrétien doit trouver entre les exigences ascétiques de la contemplation et les besoins sociaux d'une vie active. Sa pensée a également contribué à une classification des vices et vertus, ainsi que des dons du Saint-Esprit, classification dont les prédicateurs et les artistes du Moyen Âge feront grand cas.

Il reprend la classification des rêves de Macrobe et la transforme en distinguant les rêves dus à la nourriture et à la faim, ceux envoyés par les démons, et ceux d'origine divine. Considéré comme un des Pères de l'Église, il a également toujours été compté parmi les Docteurs de l'Église.