Lessico

Ippocrate

da Veterum illustrium philosophorum etc. imagines

(1685)

di Giovanni Pietro Bellori (Roma 1613-1696)

Fulvio Orsini![]()

Medico greco (Kos o Coo 460 - Larissa ca. 370 aC). Lo si dice figlio del medico

Eracleide che operò a Coo, isola greca del Mar Egeo, nel gruppo delle Sporadi

Meridionali (arcipelago del Dodecaneso). Compì molti viaggi in Tessaglia,

Tracia, Egitto e Libia![]() , ma svolse la maggior parte

della sua attività a Coo, divenendo il più noto esponente della scuola

medica ivi esistente. Viene

citato da Dante al verso 143 del IV canto dell'Infermo insieme ad altri

eminenti scienziati e personaggi della storia, soprattutto antichi greci e romani ma anche il

musulmano Saladino, che

non ebbero la buona ventura di conoscere Cristo, per cui si trovano nel Limbo,

il primo cerchio dell'Inferno dantesco. Oltre agli infanti morti senza battesimo, il poeta vi colloca le anime

di quanti non furono cristiani, ma vissero da uomini giusti e perciò non

meritarono l'Inferno vero e proprio. Questi vivono in un castello illuminato

da una luce soprannaturale (il solo luogo illuminato di tutto l'Inferno,

altrimenti immerso nell'oscurità), in una condizione malinconica ma serena.

Di questi grandi personaggi fa parte anche Virgilio

, ma svolse la maggior parte

della sua attività a Coo, divenendo il più noto esponente della scuola

medica ivi esistente. Viene

citato da Dante al verso 143 del IV canto dell'Infermo insieme ad altri

eminenti scienziati e personaggi della storia, soprattutto antichi greci e romani ma anche il

musulmano Saladino, che

non ebbero la buona ventura di conoscere Cristo, per cui si trovano nel Limbo,

il primo cerchio dell'Inferno dantesco. Oltre agli infanti morti senza battesimo, il poeta vi colloca le anime

di quanti non furono cristiani, ma vissero da uomini giusti e perciò non

meritarono l'Inferno vero e proprio. Questi vivono in un castello illuminato

da una luce soprannaturale (il solo luogo illuminato di tutto l'Inferno,

altrimenti immerso nell'oscurità), in una condizione malinconica ma serena.

Di questi grandi personaggi fa parte anche Virgilio![]() , che ha momentaneamente lasciato il suo posto tra di loro per guidare

Dante nel suo viaggio. Finalmente Benedetto XVI nel 2007 - ispirato da Dio -

si è accorto dell'iniquo anacronismo del Limbo.

, che ha momentaneamente lasciato il suo posto tra di loro per guidare

Dante nel suo viaggio. Finalmente Benedetto XVI nel 2007 - ispirato da Dio -

si è accorto dell'iniquo anacronismo del Limbo.

Pare

che Ippocrate sia stato il primo a descrivere le dita a bacchetta di tamburo

caratteristiche dell'osteopatia ipertrofizzante pneumica di Pierre Marie![]() e della sindrome di Eisenmenger

e della sindrome di Eisenmenger![]() ,

etichettate pertanto in semeiotica come dita ippocratiche. Esse si associano a

unghie a vetrino d'orologio.

,

etichettate pertanto in semeiotica come dita ippocratiche. Esse si associano a

unghie a vetrino d'orologio.

Universalmente indicato come il

fondatore della medicina scientifica, al suo nome vennero ascritte circa

settanta opere, costituenti il cosiddetto Corpus hippocraticum![]() .

Sull'effettiva paternità delle opere del Corpus, che presentano

notevoli differenze di impostazione metodologica, sono stati dati pareri

discordi. La critica più recente tende a riconoscere la presenza di un

pensiero sostanzialmente omogeneo in un gruppo di circa venti opere, tra le

quali figurano: Antica medicina, acuto esame critico degli indirizzi

medici anteriori a Ippocrate; Le arie, le acque e i luoghi, dove

si istituisce una stretta correlazione fra le malattie e le condizioni

climatiche e geografiche; Prognostico, dove è delineata una vera e

propria patologia generale degli stati morbosi; Male sacro

.

Sull'effettiva paternità delle opere del Corpus, che presentano

notevoli differenze di impostazione metodologica, sono stati dati pareri

discordi. La critica più recente tende a riconoscere la presenza di un

pensiero sostanzialmente omogeneo in un gruppo di circa venti opere, tra le

quali figurano: Antica medicina, acuto esame critico degli indirizzi

medici anteriori a Ippocrate; Le arie, le acque e i luoghi, dove

si istituisce una stretta correlazione fra le malattie e le condizioni

climatiche e geografiche; Prognostico, dove è delineata una vera e

propria patologia generale degli stati morbosi; Male sacro![]() , in cui si

afferma che l'epilessia è dovuta a cause naturali, come le altre malattie, e

non all'intervento di divinità; Epidemie, sistematica raccolta di

osservazioni circa le malattie che si diffusero nell'isola di Taso in

relazione a determinate vicende atmosferiche; il Giuramento, vero e

proprio manifesto morale della scuola.

, in cui si

afferma che l'epilessia è dovuta a cause naturali, come le altre malattie, e

non all'intervento di divinità; Epidemie, sistematica raccolta di

osservazioni circa le malattie che si diffusero nell'isola di Taso in

relazione a determinate vicende atmosferiche; il Giuramento, vero e

proprio manifesto morale della scuola.

da

Histoire de la médecine par Daniel Le Clerc

Amsterdam - 1702

Caratteristica generale dell'impostazione metodologica avviata da Ippocrate è la critica di ogni concezione aprioristica e quindi il ricorso all'esperienza. Egli, infatti, condusse una decisa polemica nei confronti della tradizione medica ancora operante alla sua epoca e inserita in un contesto mistico religioso. Problema centrale dei suoi studi fu perciò quello di dare alla medicina uno strumento teorico di spiegazione efficace e un metodo di indagine che giustificasse e potenziasse il legame fra teoria ed esperienza. Lo schema teorico generale elaborato dalla scuola ippocratica consiste essenzialmente nella dottrina dei quattro umori, un'originale derivazione dalle teorie degli elementi primordiali.

Secondo tale teoria gli umori, o elementi fondamentali costitutivi del corpo umano, sono: il sangue, elemento caldo proveniente dal cuore, la flemma, elemento freddo che proviene dal cervello; la bile gialla, asciutta, secreta dal fegato; e la bile nera, elemento umido, prodotta dalla milza. La salute di un organismo viene ricondotta a un rapporto proporzionato (crasi) fra i vari umori. Allorché questo rapporto viene alterato (discrasia) si origina la malattia che, secondo il particolare umore alterato, si distingue in sanguigna, flemmatica, biliare e atrobiliare. Subentra allora un periodo critico in cui l'organismo oppone resistenza agli agenti esterni responsabili della malattia.

Compito del medico è di aiutare l'organismo in questa lotta cercando di ripristinare le giuste condizioni per il suo funzionamento, soprattutto facendo in modo da rendere inoffensivi tutti i fattori esterni che hanno causato la malattia. Da questo punto di vista la malattia non è considerata come un fatto improvviso o accidentale: essa ha una storia che può essere ricostruita attraverso l'individuazione delle cause che l'hanno resa operante e una previsione della loro efficacia futura resa possibile dalla numerosa precettistica desunta fondamentalmente dall'esperienza. Secondo tale originale indirizzo, la terapia si riduce ad assecondare la forza medicatrice della natura; di qui l'importanza della dieta e delle norme igieniche che tendono a ripristinare, correggendo le anomalie, l'equilibrio precedente. La medicina ippocratica ha esercitato un'enorme influenza lungo tutta la storia del pensiero scientifico; ciò in massima parte è dovuto all'assetto metodico e non dogmatico conferito alla medicina da Ippocrate e dalla sua scuola che le consentì di sopravvivere a ogni conquista dottrinale e di essere riscoperta in epoche diverse nella sua funzione di guida e di orientamento teorico e deontologico.

Ippocrate

e Galeno![]() vigilano sul malato e sui medici che lo assistono

vigilano sul malato e sui medici che lo assistono

Giuramento di Ippocrate

Janus

Cornarius![]() aveva così tradotto dal greco in latino il giuramento di Ippocrate:

aveva così tradotto dal greco in latino il giuramento di Ippocrate:

«Apollinem

medicum![]() et Aesculapium

et Aesculapium![]() Hygeamque ac Panaceam iuro deosque omnes itemque deas

testes facio me hoc iusiurandum et hanc contestationem conscriptam pro viribus

et iudicio meo integre servaturum esse: Praeceptorem sane qui me hanc edocuit

artem, parentum loco habiturum, vitam communicaturum, eaque quibus opus

habuerit impertiturum: eos item qui ex eo nati sunt pro fratribus masculis

iudicaturum artemque hanc, si discere voluerint, absque mercede et pacto

edocturum: praeceptionum, ac auditionum, reliquaeque totius disciplinae

participes facturum, tum meos, tum praeceptoris mei filios, imo et discipulos,

qui mihi scripto caverint, et medico iureiurando addicti fuerint, alii vero

praeter hos nulli. Ceterum quod ad aegros attinet sanandos, diaetam ipsis

constitutam pro facultate et iudicio meo commodam, omneque detrimentum et

iniuriam ab eis prohibebo. Neque vero ullius preces apud me adeo validae

fuerint, ut cuipiam venenum sim propinaturus, neque etiam ad hanc rem

consilium dabo. Similiter autem neque mulieri talum vulvae subditicium, ad

corrumpendum conceptum, vel foetum dabo. Porro praeterea et sancte vitam et

artem meam conservabo. Nec vero calculo laborantes secabo, sed viris

chirurgiae operariis eius rei faciendae locum dabo. In quascumque autem domos

ingrediar, ob utilitatem aegrotantium intrabo, ab omnique iniuria voluntaria

inferenda, et corruptione cum alia, tum praesertim operum venereorum abstinebo,

sive muliebria sive virilia, liberorumve hominum aut servorum corpora mihi

contigerint curanda. Quaecumque vero inter curandum videro aut audiero, imo

etiam ad medicandum non adhibitus in communi hominum vita cognovero, ea

siquidem efferre non contulerit, tacebo: et tanquam arcana apud me continebo.

Hoc igitur iusiurandum mihi integre servanti, et non confundenti, contingat et

vita et arte feliciter frui, et apud omnes homines in perpetuum gloriam meam

celebrari. Transgredienti autem et peieranti, his contraria eveniant.» - Hippocratis

Coi medicorum omnium longe principis, opera quae ad nos extant omnia (Froben,

Basilea, 1546)

Hygeamque ac Panaceam iuro deosque omnes itemque deas

testes facio me hoc iusiurandum et hanc contestationem conscriptam pro viribus

et iudicio meo integre servaturum esse: Praeceptorem sane qui me hanc edocuit

artem, parentum loco habiturum, vitam communicaturum, eaque quibus opus

habuerit impertiturum: eos item qui ex eo nati sunt pro fratribus masculis

iudicaturum artemque hanc, si discere voluerint, absque mercede et pacto

edocturum: praeceptionum, ac auditionum, reliquaeque totius disciplinae

participes facturum, tum meos, tum praeceptoris mei filios, imo et discipulos,

qui mihi scripto caverint, et medico iureiurando addicti fuerint, alii vero

praeter hos nulli. Ceterum quod ad aegros attinet sanandos, diaetam ipsis

constitutam pro facultate et iudicio meo commodam, omneque detrimentum et

iniuriam ab eis prohibebo. Neque vero ullius preces apud me adeo validae

fuerint, ut cuipiam venenum sim propinaturus, neque etiam ad hanc rem

consilium dabo. Similiter autem neque mulieri talum vulvae subditicium, ad

corrumpendum conceptum, vel foetum dabo. Porro praeterea et sancte vitam et

artem meam conservabo. Nec vero calculo laborantes secabo, sed viris

chirurgiae operariis eius rei faciendae locum dabo. In quascumque autem domos

ingrediar, ob utilitatem aegrotantium intrabo, ab omnique iniuria voluntaria

inferenda, et corruptione cum alia, tum praesertim operum venereorum abstinebo,

sive muliebria sive virilia, liberorumve hominum aut servorum corpora mihi

contigerint curanda. Quaecumque vero inter curandum videro aut audiero, imo

etiam ad medicandum non adhibitus in communi hominum vita cognovero, ea

siquidem efferre non contulerit, tacebo: et tanquam arcana apud me continebo.

Hoc igitur iusiurandum mihi integre servanti, et non confundenti, contingat et

vita et arte feliciter frui, et apud omnes homines in perpetuum gloriam meam

celebrari. Transgredienti autem et peieranti, his contraria eveniant.» - Hippocratis

Coi medicorum omnium longe principis, opera quae ad nos extant omnia (Froben,

Basilea, 1546)

Il Corpus hippocraticum è una collezione di circa settanta opere che trattano vari temi, tra cui spicca la medicina, scritte in greco antico nel corso di vari secoli e aggregate tra di loro in un'epoca imprecisata. L'attribuzione delle singole opere è estremamente complessa: alcune sono attribuibili a Ippocrate mentre altre derivano senz'altro dall'influenza che egli ebbe nei secoli successivi.

Quest'opera presenta contenuti davvero innovativi, tanto da poter considerare Ippocrate il fondatore della scienza medica, avendo egli conferito per la prima volta carattere autonomo e specifico a una pratica fino ad allora empirica. Egli riteneva infatti che qualsiasi manifestazione morbosa dovesse essere affrontata razionalmente. Celebre è la discussione sull'epilessia (discussa nel trattato De morbo sacro), chiamata appunto all'epoca malattia sacra perché ritenuta di origine divina e quindi non curabile con mezzi naturali. Secondo l'autore, infatti, l'appello alla divinità sarebbe solo un modo per mascherare l'ignoranza ed esimersi dalla ricerca delle vere cause.

Tra le opere che compaiono nella raccolta meritano particolare attenzione Delle arie, delle acque e dei luoghi, uno studio sull'influenza dell'ambiente sulla salute dell'uomo, Sulle epidemie, il Prognostico, Sulle fratture e Sulla riduzione degli arti. Un posto predominante spetta poi al Giuramento di Ippocrate, in cui sono enunciati i fondamenti dell'etica medica.

Opere del Corpus - Hippocratis jusiurandum - Hippocratis lex - De arte - De veteri medicina - De medico - De decenti ornatu - Praeceptiones - De natura hominis - De salubri diaeta - De genitura - De natura pueri - De carnibus - De septimestri partu - De octimestri partu - De superfoetatione - De exectione foetus - De dentitione - De corporum resectione - De corde - De glandulis - De ossium natura - De locis in homine - De aere, aquis et locis - De flatibus - De medicamentis purgantibus - De diaeta libri III - De insomniis - De alimento - De humidorum usu - De humoribus - De morbo sacro - De morbis libri IV - De affectionibus - De internis affectionibus - De virginum morbo - De natura muliebri - De morbis muliebribus - De morbis muliebribus liber II - De sterilibus - De morbis popularibus libri VII - De victus ratione in morbis - De judicationibus - De diebus judicatoriis - Aphorismorum - Praenotionum - Praedictionum libri II - Coacae praenotiones - De capitis vulneribus - Chirurgiae officina - De fracturis - De articulis - De ulceribus - De fistulis - De haemorrhoidibus - De visu - Epistolae.

De

morbo sacro

Il male sacro – La malattia sacra

Anticamente

la malattia neurologica dell'epilessia veniva definita morbo sacro. Ciò era dovuto

all'inspiegabilità e all'imprevedibilità delle sue manifestazioni, che per

molto tempo contribuirono a ritenerla causata da forze maligne della natura o

da divinità avverse. Infatti nell'antica Grecia, tanto la religione quanto la

dottrina medica dei sacerdoti-medici nei templi di Esculapio![]() , concepivano come normale

un diretto intervento delle divinità sulla vita dell'uomo e dunque sulle

malattie.

, concepivano come normale

un diretto intervento delle divinità sulla vita dell'uomo e dunque sulle

malattie.

Diversi erano i rituali utilizzati per la guarigione dall'epilessia tra cui la pratica dell'incubazione (consistente nel far dormire sopra una lastra di pietra nel tempio di Esculapio, dio della medicina, l'individuo affetto da epilessia), l'uso di semi e radici di peonia o della polvere delle ossa di cranio o di sangue umano. Era accertata inoltre l'influenza della luna piena sulla ricorrenza degli attacchi epilettici.

Ippocrate fu il primo grande personaggio del passato a rifiutare il carattere sovrannaturale di questa malattia, come dimostra nel suo trattato specifico sull'epilessia intitolato De morbo sacro. Il suo contributo fu fondamentale per elevare la scienza medica a modello di sapere scientifico.

Ippocrate riteneva che tale malattia avesse struttura naturale e cause razionali e nella sua opera chiarisce come in essa non ci fosse nulla di più divino e sacro che nelle altre malattie. Era piuttosto l'ignoranza degli uomini (quelli che l'autore definisce ciarlatani, maghi, bigotti, stregoni) riguardo le cause e le cure dell'epilessia che li stupiva per la stranezza delle sue manifestazioni, che contribuiva all'erronea credenza per cui era ritenuta di origine divina.

È infatti contro le antiche terapie magiche che gli ippocratici rivolgono la loro polemica, proclamando la loro fiducia nella ragione, capace di cogliere le cause naturali e razionali di questo fenomeno e di spiegarlo, e affermando quindi l'autonomia dell'arte medica. L'autore mette in luce, inoltre, l'impossibilità che l'uomo possa essere contaminato da un dio: essendo infatti il primo corruttibile e il secondo sacro, ne sarebbe al massimo purificato e santificato ma certamente non offeso. Infine egli sottolinea come l'epilessia abbia origini di tipo ereditario ed embriologico, connesse con una malformazione del cervello.

Con grande attualità, Ippocrate afferma il ruolo centrale del cervello come sede di tale malattia e di tutte le malattie mentali. È in esso infatti che si formano i piaceri, la serenità, l'allegria, è grazie a esso che pensiamo, ragioniamo e giudichiamo; esso è però anche causa di pazzia, deliri, smarrimenti e incapacità di comprendere cose consuete.

Nel trattato l'autore descrive con grande precisione la struttura anatomica del cervello precisando come questo sia doppio (come quello di tutti gli altri animali) e diviso da una sottile meninge, e come possa talvolta, per una malformazione embriologica, contenere flegma in eccesso da cui non riesce a purificarsi. Questo fluido, dunque, attraverso le due grandi vene che giungono al cervello dalla milza e dal fegato per raccogliere l'aria da distribuire, si dirigerà nel resto del corpo ostacolandone la necessaria aerazione. Potrà accadere, ad esempio, che vada verso il cuore, provocando in tal caso palpitazioni e asma poiché quando il flegma freddo scende verso i polmoni raggela anche il sangue, e le vene raffreddate a forza battono contro il petto fino a che sopraggiunge la dispnea.

Addirittura vengono messi in evidenza i diversi effetti di tale morbo nel bambino e nell'adulto, o a seconda che i venti spirino da nord o da sud. Ma è interessante notare che l'attenta analisi ippocratica delle svariate condizioni in cui l'epilessia si manifesta, non fa altro che confermare la validità della teoria umorale ippocratica fondata sul contrasto di caldo e di freddo, di sangue e di flegma.

D'altronde questo tentativo di unire anatomia e fisiologia e quindi strutture anatomiche, proprietà degli umori (sangue-caldo, flegma-freddo) e condizioni esterne (come i venti), al fine di fornire una spiegazione dei fenomeni sorprendenti che accompagnano le crisi epilettiche (e le malattie più in generale), è il fondamento del sapere ippocratico.

Icones veterum aliquot ac recentium Medicorum

Philosophorumque

Ioannes Sambucus / János Zsámboky![]()

Antverpiae 1574

Hippocrates of Cos or Hippokrates of Kos (ca. 460 BC – ca. 370 BC) - Greek: Ἱπποκράτης; Hippokrátës was an ancient Greek physician of the Age of Pericles, and was considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of medicine. He is referred to as the "father of medicine" in recognition of his lasting contributions to the field as the founder of the Hippocratic School of medicine. This intellectual school revolutionized medicine in ancient Greece, establishing it as a discipline distinct from other fields that it had traditionally been associated with (notably theurgy and philosophy), thus making medicine a profession.

However, the achievements of the writers of the Corpus, the practitioners of Hippocratic medicine, and the actions of Hippocrates himself are often commingled; thus very little is known about what Hippocrates actually thought, wrote, and did. Nevertheless, Hippocrates is commonly portrayed as the paragon of the ancient physician. In particular, he is credited with greatly advancing the systematic study of clinical medicine, summing up the medical knowledge of previous schools, and prescribing practices for physicians through the Hippocratic Oath and other works.

Biography

Asklepieion on Kos

Historians accept that Hippocrates was born around the year 460 BC on the Greek island of Kos (Cos), and became a famous physician and teacher of medicine. Other biographical information, however, is likely to be untrue (see Legends). Soranus of Ephesus, a 2nd-century Greek gynecologist, was Hippocrates' first biographer and is the source of most information on Hippocrates' person. Information about Hippocrates can also be found in the writings of Aristotle, which date from the 4th century BC, in the Suda of the 10th century AD, and in the works of John Tzetzes, which date from the 12th century AD. Soranus wrote that Hippocrates' father was Heraclides, a physician; his mother was Praxitela, daughter of Tizane. The two sons of Hippocrates, Thessalus and Draco, and his son-in-law, Polybus, were his students. According to Galen, a later physician, Polybus was Hippocrates' true successor, while Thessalus and Draco each had a son named Hippocrates.

Soranus said that Hippocrates learned medicine from his father and grandfather, and studied other subjects with Democritus and Gorgias. Hippocrates was probably trained at the asklepieion of Kos, and took lessons from the Thracian physician Herodicus of Selymbria. The only contemporaneous mention of Hippocrates is in Plato's dialogue Protagoras, where Plato describes Hippocrates as "Hippocrates of Kos, the Asclepiad". Hippocrates taught and practiced medicine throughout his life, traveling at least as far as Thessaly, Thrace, and the Sea of Marmara. He probably died in Larissa at the age of 83 or 90, though some accounts say he lived to be well over 100; several different accounts of his death exist.

Hippocratic theory

Hippocrates is credited with being the first physician to reject superstitions, legends and beliefs that credited supernatural or divine forces with causing illness. Hippocrates was credited by the disciples of Pythagoras of allying philosophy and medicine. He separated the discipline of medicine from religion, believing and arguing that disease was not a punishment inflicted by the gods but rather the product of environmental factors, diet, and living habits. Indeed there is not a single mention of a mystical illness in the entirety of the Hippocratic Corpus. However, Hippocrates did work with many convictions that were based on what is now known to be incorrect anatomy and physiology, such as Humorism.

Ancient Greek schools of medicine were split (into the Knidian and Koan) on how to deal with disease. The Knidian school of medicine focused on diagnosis. Medicine at the time of Hippocrates knew almost nothing of human anatomy and physiology because of the Greek taboo forbidding the dissection of humans. The Knidian school consequently failed to distinguish when one disease caused many possible series of symptoms. The Hippocratic school or Koan school achieved greater success by applying general diagnoses and passive treatments. Its focus was on patient care and prognosis, not diagnosis. It could effectively treat diseases and allowed for a great development in clinical practice.

Hippocratic medicine and its philosophy are far removed from that of modern medicine. Now, the physician focuses on specific diagnosis and specialized treatment, both of which were espoused by the Knidian school. This shift in medical thought since Hippocrates' day has caused serious criticism over the past two millennia, with the passivity of Hippocratic treatment being the subject of particularly strong denunciations; for example, the French doctor M. S. Houdart called the Hippocratic treatment a "meditation upon death".

Humorism and crisis

The Hippocratic school held that all illness was the result of an imbalance in the body of the four humours, fluids which in health were naturally equal in proportion (pepsis). When the four humours, blood, black bile, yellow bile and phlegm, were not in balance (dyscrasia, meaning "bad mixture"), a person would become sick and remain that way until the balance was somehow restored. Hippocratic therapy was directed towards restoring this balance. For instance, using citrus was thought to be beneficial when phlegm was overabundant.

Another important concept in Hippocratic medicine was that of a crisis, a point in the progression of disease at which either the illness would begin to triumph and the patient would succumb to death, or the opposite would occur and natural processes would make the patient recover. After a crisis, a relapse might follow, and then another deciding crisis. According to this doctrine, crises tend to occur on critical days, which were supposed to be a fixed time after the contraction of a disease. If a crisis occurred on a day far from a critical day, a relapse might be expected. Galen believed that this idea originated with Hippocrates, though it is possible that it predated him.

Hippocratic medicine was humble and passive. The therapeutic approach was based on "the healing power of nature" ("vis medicatrix naturae" in Latin). According to this doctrine, the body contains within itself the power to re-balance the four humours and heal itself (physis). Hippocratic therapy focused on simply easing this natural process. To this end, Hippocrates believed "rest and immobilization [were] of capital importance". In general, the Hippocratic medicine was very kind to the patient; treatment was gentle, and emphasized keeping the patient clean and sterile. For example, only clean water or wine were ever used on wounds, though "dry" treatment was preferable. Soothing balms were sometimes employed.

Hippocrates was reluctant to administer drugs and engage in specialized treatment that might prove to be wrongly chosen; generalized therapy followed a generalized diagnosis. Potent drugs were, however, used on certain occasions. This passive approach was very successful in treating relatively simple ailments such as broken bones which required traction to stretch the skeletal system and relieve pressure on the injured area. The Hippocratic bench and other devices were used to this end.

One of the strengths of Hippocratic medicine was its emphasis on prognosis. At Hippocrates' time, medicinal therapy was quite immature, and often the best thing that physicians could do was to evaluate an illness and induce its likely progression based upon data collected in detailed case histories.

Professionalism

Hippocratic medicine was notable for its strict professionalism, discipline and rigorous practice. The Hippocratic work On the Physician recommends that physicians always be well-kempt, honest, calm, understanding, and serious. The Hippocratic physician paid careful attention to all aspects of his practice: he followed detailed specifications for, "lighting, personnel, instruments, positioning of the patient, and techniques of bandaging and splinting" in the ancient operating room. He even kept his fingernails to a precise length.

The Hippocratic School gave importance to the clinical doctrines of observation and documentation. These doctrines dictate that physicians record their findings and their medicinal methods in a very clear and objective manner, so that these records may be passed down and employed by other physicians. Hippocrates made careful, regular note of many symptoms including complexion, pulse, fever, pains, movement, and excretions. He is said to have measured a patient's pulse when taking a case history to know if the patient lied. Hippocrates extended clinical observations into family history and environment. "To him medicine owes the art of clinical inspection and observation". For this reason, he may more properly be termed as the "Father of Clinical Medicine".

Direct contributions to medicine

Clubbing

of fingers in a patient with Eisenmenger's syndrome![]() .

.

Clubbing was first described by Hippocrates,

then clubbing is also known as "Hippocratic fingers".

Hippocrates and his followers were first to describe many diseases and medical conditions. He is given credit for the first description of clubbing of the fingers, an important diagnostic sign in chronic suppurative lung disease, lung cancer and cyanotic heart disease. For this reason, clubbed fingers are sometimes referred to as "Hippocratic fingers". Hippocrates was also the first physician to describe Hippocratic face in Prognosis. Shakespeare famously alludes to this description when writing of Falstaff's death in Act II, Scene iii. of Henry V.

Hippocrates began to categorize illnesses as acute, chronic, endemic and epidemic, and use terms such as, "exacerbation, relapse, resolution, crisis, paroxysm, peak, and convalescence." Another of Hippocrates' major contributions may be found in his descriptions of the symptomatology, physical findings, surgical treatment and prognosis of thoracic empyema, i.e. suppuration of the lining of the chest cavity. His teachings remain relevant to present-day students of pulmonary medicine and surgery. Hippocrates was the first documented chest surgeon and his findings are still valid.

The Hippocratic school of medicine described well the ailments of the human rectum and the treatment thereof, despite the school's poor theory of medicine. Hemorrhoids, for instance, though believed to be caused by an excess of bile and phlegm, were treated by Hippocratic physicians in relatively advanced ways. Cautery and excision are described in the Hippocratic Corpus, in addition to the preferred methods: ligating the hemorrhoids and drying them with a hot iron. Other treatments such as applying various salves are suggested as well. Today, "treatment [for hemorrhoids] still includes burning, strangling, and excising". Also, some of the fundamental concepts of proctoscopy outlined in the Corpus are still in use. For example, the uses of the rectal speculum, a common medical device, are discussed in the Hippocratic Corpus. This constitutes the earliest recorded reference to endoscopy.

Hippocratic Corpus

The Hippocratic Corpus (Latin: Corpus hippocraticum), Hippocratic Collection, or Hippocratic Canon, is a collection of around seventy early medical works from ancient Greece strongly associated with the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates and his teachings. They are, however, varied in content, age and style, and are largely of unknown authorship.

Of the volumes in the Corpus, none is proven to be of Hippocrates' hand itself, though some sources say otherwise. Instead, the works were probably produced by students and followers of him (Ermerins numbers the authors at nineteen - Franz Zacharias Ermerins, 8 November 1808 Middelburg - 29 May 1871 Groningen), maybe centuries after he died. Because of the variety of subjects, writing styles and apparent date of construction, scholars believe it could not have been written by one person. But the corpus carries Hippocrates's name as it was attributed to him in antiquity and its teaching generally follow principles of his. It might be the remains of a library of Kos, or a collection compiled in the third century BC in Alexandria. It was not, however, only the Koan school of ancient Greek medicine that contributed to the Corpus; the Knidian did, too.

The Hippocratic Corpus contains textbooks, lectures, research, notes and philosophical essays on various subjects in medicine, in no particular order. These works were written for different audiences, both specialists and laymen, and were sometimes written from opposing view points; significant contradictions can be found between works in the Corpus. One significant portion of the corpus is made up of case-histories, of which there are forty-two. Of these, 60% (25) ended in the patient's death. Nearly all of the diseases described in the Corpus are endemic diseases: colds, consumption, pneumonia, etc.

The writing style of the Corpus has been remarked upon for centuries, being described by some as, "clear, precise, and simple". It is often praised for its objectivity and conciseness, yet some have criticized it as being "grave and austere". Francis Adams, a translator of the Corpus, goes further and calls it sometimes “obscure”. Of course, not all of the Corpus is of this “laconic” style, though most of it is. It was Hippocratic practice to write in this style. The whole corpus is written in Ionic Greek, though the island of Kos was in a region that spoke Doric Greek. This use of Ionic instead of the native Doric dialect is analogous to the practice of Renaissance scientists, using Latin instead of the vernacular for their treatises.

The entire Hippocratic Corpus was first printed as a unit in 1525. This edition was in Latin and was edited by Marcus Fabius Calvus in Rome. The first complete Greek edition followed the next year in Venice. An English translation was first published about 300 years later. A significant edition was that of Émile Littré who spent twenty-two years (1839–1861) working diligently on the Hippocratic Corpus. This was scholarly, yet sometimes inaccurate and awkward. Another edition of note was that of Franz Zacharias Ermerins, published in Utrecht between 1859 and 1864. Beginning in 1967, an important modern edition by Jacques Jouanna and others began to appear (with Greek text, French translation, and commentary) in the Collection Budé. Other important bilingual annotated editions (with translation in German or French) continue to appear in the Corpus medicorum graecorum published by the Akademie-Verlag in Berlin.

The most famous work in the Hippocratic corpus is the Hippocratic Oath, a landmark declaration of doctoral ethics. The Hippocratic Oath is both philosophical and practical; it not only deals with abstract principles but practical matters such as removing stones and aiding one's teacher financially. It is a complex and probably not the work of one man.

Though it is of unknown origin, like many other works from the time period, it is included in the Corpus and named after Hippocrates for historic tradition. Indeed, this short work has become a very important work in the history of medicine. Traditionally, it has been taken at the beginning of a doctor's career, perhaps to medical school graduates. Because of its antiquity, however, the Oath is rarely taken in its original form today. But, it does serve as a foundation for other, similar oaths and laws that define good medical practice and morals; derivatives of which are still taken.

List of works of the Corpus - 1. The Prognostics - 2. On Airs, Waters, and Places - 3. On Regimen in Acute Diseases. - 4. The Aphorisms - 5. The Epidemics - 6. On the Articulations - 7. On Fractures - 8. On the Instruments of Reduction - 9. The Hippocratic Oath - 10. On Ancient Medicine - 11. On Fractures - 12. The Instruments of Reduction - 13. The Physician's Establishment or Surgery - 14. On Injuries of the Head - 15. The Law - 16. On the Nature of Man - 17. Regimen of Persons in Health - 18. The Coan Praenotions - 19. Prorrhetics - 20. Of Ulcers - 21. Of Fistulae - 22. Of Hemorrhoids - 23. Of the Pneuma - 24. On the Sacred Disease - 25. Of the Places in Man - 26. Of Art - 27. Of Regimen, and of Dreams - 28. Of Affections - 29. Of Internal Affections - 30. Of Diseases - 31. Of the Seventh Month Foetus - 32. Of the Eighth Month Foetus - 33. On the Surgery - 34. On Generation - 35. On the Nature of the Infant - 36. On the Diseases of Women - 37. On the Diseases of Young Women - 38. On Unfruitful Women - 39. On Superfoetation - 40. On the Heart - 41. On Aliment - 42. On Fleshes - 43. On the Weeks - 44. On the Glands - 45. On the Nature of Bones - 46. On the Physician - 47. On Honorable Conduct - 48. Precepts - 49. On Anatomy - 50. On the Sight - 51. On Dentition - 52. On the Nature of the Woman - 53. On the Excision of the Foetus - 54. On Crisis - 55. On Critical Days - 56. On Purgative Medicines - 57. On dangerous Wounds (lost) - 58. On Missiles and Wounds (lost).

On the Sacred Disease

On the Sacred Disease is one piece of a large collection of medical literature in the Hippocratic Corpus. The Hippocratic Corpus itself is a large collection of approximately sixty medical works, the majority of which date from the last decades of the 5th century BC to the first half of the 4th century. On the Sacred Disease was written in 400 BC. The authorship of this piece, along with the others, can not be confirmed and is therefore regarded as dubious in origin by historians. On the Sacred Disease is thought to contain the first recorded observations of epilepsy in humans. Hippocrates describes this phenomena being related to an imbalance in the four humors and not of divine origin. This thought process was a major break through in the beginnings of medicinal history.

Hippocratic

physicians all described illness by use of the four humors. These Humors

consist of blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. According to this

theory, every person has different concentrations of each one of these

components depending on what season they are born. Any imbalance in these

humors results in pain and illness. They believed that such flux of the humors

could occur at any time and with freedom in destination. Such infections

affect the internal organs of a body causing them to absorb and swell in the

presence of a disease.

The humors are each associated with a combination of four basic qualities:

hot, cold, moist, and dry. From these characteristics, certain humors would

predominate during different seasons. For example, phlegm is a cold humor

which is strongly associated with the season winter. Blood was primarily

associated with the spring, yellow bile in the summer, and black bile in the

autumn. However, seasonal factors were only one of the reasons used for

diagnosis by early Hippocratic physicians.

The Hippocratic Corpus further explained these imbalances as being the product

of what was occurring in a given person’s “diet.” Here the term diet is

used to loosely encompass everything in an individual’s lifestyle such as

food, sleep, exercise, environment, etc. Treatment to cure such an imbalance

was by prescribing certain eating habits or a fitness regimen. Therefore

medicine was a regulatory and balanced complexion. Hippocrates did not believe

that incantations and praying rituals were of any use to the ill. Since he

believed that disease was a result of human imbalance, there was no need to

cure a patient of evil spirits or dislodging them from the disfavor of an

angered god.

Hippocrates comments on the "Sacred" disease declaring that it is no more sacred than other diseases present during the Hellenistic era. He stresses the importance of the disease having no relation with the divine whatsoever, but instead being purely of human origin. Symptoms of this disease are described as men becoming mad either by crying out, suffocating on saliva, frothing by the mouth, or by shaking uncontrollably. Such symptoms were thought to be a punishment from the gods on an individual. Hippocrates continues his argument by noting that such phenomena is not of divine origin because previous treatments to the affected involved incantations and pray patterns that were unsuccessful.

The text continues with the known anatomy of the brain at the time. The brain of a human is similar to other animals in that it is double and divided by a thin membrane through the middle. Hippocrates attributes this fact for the reason that a patients pain isn't always located in the same spot on his or her head. Veins from the bodies major organs connect to the brain and vary in size. The veins that run along the right region of the body through the heart and lungs are continued to be described to the best of Hippocrates' knowledge:

"The other runs upward by the right veins in the lungs and divides into branches for the heart and the right arm. The remaining part of it rises up the upward across the clavicle to the right side of the neck, and is superficial so as to be seen; near the ear it is concealed, and there it divides; it's thickest, largest, and most hollow part ends in the brain; another small vein goes to the right ear, another to the right eye, and another to the nostril. Such are the distributions of the hepatic vein."

Hippocrates argues that the start of this Sacred disease begins with the accumulation of phlegm (one of the four humors) in the veins of the head. This build up begins to be formed in uterus. If this disease continues to grow after birth and into adulthood, the affected person will have a "melted" brain which results in mental illness. Once the disease is stuck within the head, the patient loses his speech and chokes causing foam to fall from his or her mouth.

Young children that obtain the disease mostly die Hippocrates argues that due to their small veins, they are not able to accommodate the increased amount of phlegm. When the phlegm gathers the child quickly "cools" and the blood congeals causing death. The elderly for the most part survive the disease due to the Hippocratic theory that their veins are larger and filled with hot flowing blood that is safe from the coldness of the phlegm. Many of the afflicted seem to know when they are about to have another episode. When this happens, they become ashamed and flee from the surrounding crowd to hide. Hippocrates mentions that this is due to the fear of the divine and embarrassment that they have been punished with the "Sacred" disease.

Hippocrates concludes that the Sacred disease is proof that the brain has the greatest power over man. It is through this part of the body that air from breathing first enters. When the disease dilutes the mind to the point where phlegm in the veins increases sufficiently causing air blockage, is when the patient begins to suffer and possibly die.

Hippocrates is an influential beginning to the modern medicinal world. He attempted to move away from the Gods as being the cause of disease by using more naturalistic terms just as the early Mileasians and Aristotelians supported their arguments. However, not only did Hippocrates’ work reflect these concepts, it manifested them. He clearly defined what he believed was and what wasn’t medicine. He preached that previous methods of medicine involving the aid of the gods were based on ignorance. In On the Sacred Disease, he argued that even the most mysterious of diseases was still of natural cause and not of divine origin: “Men regard its nature and cause as divine from ignorance and wonder because it is not at all like to other diseases… Men being in want of the means of life, invent many and various things, and devise many contrivances for all other things and for this disease, in every phase of the disease, assigning the cause to a god… Neither truly do I count it a worth opinion to hold that the body of man is polluted by god, the most impure by the most holy.”

Early methods to treat disease and injuries were based on the notion to please the potentially angered gods, and once the gods were happy, the victim would be cured. People chose to use gods as the explanations of the unexplained. The act of praying, incantations, and sacrifices were not considered by Hippocrates to be of any medicinal value. He believed in the discoverability of nature, the reality that disease is not of divine origin but instead, it is a human problem that can be solved medically. For example, in order to explain illness he proposed the idea of the four Humors, each body producing a negative response whenever there is an imbalance.

Hippocratic Oath

The Hippocratic Oath, a seminal document on the ethics of medical practice, was attributed to Hippocrates in antiquity although new information shows it may have been written after his death. This is probably the most famous document of the Hippocratic Corpus. Recently the authenticity of the documents author has come under scrutiny. While the Oath is rarely used in its original form today, it serves as a foundation for other, similar oaths and laws that define good medical practice and morals. Such derivatives are regularly taken today by medical graduates about to enter medical practice.

Legacy

Hippocrates is widely considered to be the "Father of Medicine". His contributions revolutionized the practice of medicine; but after his death the advancement stalled. So revered was Hippocrates that his teachings were largely taken as too great to be improved upon and no significant advancements of his methods were made for a long time. The centuries after Hippocrates' death were marked as much by retrograde movement as by further advancement. For instance, "after the Hippocratic period, the practice of taking clinical case-histories died out...", according to Fielding Garrison. After Hippocrates, the next significant physician was Galen, a Greek who lived from 129 to 200 AD. Galen perpetuated Hippocratic medicine, moving both forward and backward. In the Middle Ages, Arabs adopted Hippocratic methods. After the European Renaissance, Hippocratic methods were revived in Europe and even further expanded in the 19th century. Notable among those who employed Hippocrates' rigorous clinical techniques were Sydenham, Heberden, Charcot and Osler. Henri Huchard, a French physician, said that these revivals make up "the whole history of internal medicine".

Image

According to Aristotle's testimony, Hippocrates was known as "the Great Hippocrates". Concerning his disposition, Hippocrates was first portrayed as a "kind, dignified, old country doctor'" and later as "stern and forbidding". He is certainly considered wise, of very great intellect and especially as very practical. Francis Adams describes him as "strictly the physician of experience and common sense". His image as the wise, old doctor is reinforced by busts of him, which wear large beards on a wrinkled face. Many physicians of the time wore their hair in the style of Jove and Asklepius. Accordingly, the busts of Hippocrates that we have could be only altered versions of portraits of these deities. Hippocrates and the beliefs that he embodied are considered medical ideals. Fielding Garrison, an authority on medical history, stated, "He is, above all, the exemplar of that flexible, critical, well-poised attitude of mind, ever on the lookout for sources of error, which is the very essence of the scientific spirit". "His figure... stands for all time as that of the ideal physician”, according to A Short History of Medicine, inspiring the medical profession since his death.

Legends

Most stories of Hippocrates' life are likely to be untrue because of their inconsistency with historical evidence, and because similar or identical stories are told of other figures such as Avicenna and Socrates, suggesting a legendary origin. Even during his life, Hippocrates' renown was great, and stories of miraculous cures arose. For example, Hippocrates was supposed to have aided in the healing of Athenians during the Plague of Athens by lighting great fires as "disinfectants" and engaging in other treatments. There is a story of Hippocrates curing Perdiccas, a Macedonian king, of "love sickness". Neither of these accounts is corroborated by any historians and they are thus unlikely to have ever occurred.

Another legend concerns how Hippocrates rejected a formal request to visit the court of Artaxerxes, the King of Persia. The validity of this is accepted by ancient sources but denied by some modern ones, and is thus under contention. Another tale states that Democritus was supposed to be mad because he laughed at everything, and so he was sent to Hippocrates to be cured. Hippocrates diagnosed him as having a merely happy disposition. Democritus has since been called "the laughing philosopher".

Not all stories of Hippocrates portrayed him in a positive manner. In one legend, Hippocrates is said to have fled after setting fire to a healing temple in Greece. Soranus of Ephesus, the source of this story, names the temple as the one of Knidos. However centuries later, the Byzantine Greek grammarian John Tzetzes, writes that Hippocrates burned down his own temple, the Temple of Cos, speculating that he did it to maintain a monopoly of medical knowledge. This account is very much in conflict with traditional estimations of Hippocrates' personality. Other legends tell of his resurrection of Augustus' nephew; this feat was supposedly created by the erection of a statue of Hippocrates and the establishment of a professorship in his honor in Rome.

Genealogy

Hippocrates' legendary genealogy traces his paternal heritage directly to Asklepius and his maternal ancestry to Heracles. According to Tzetzes' Chiliades, the ahnentafel of Hippocrates II is:

1.

Hippocrates II The Father of Medicine

2. Heraclides

4. Hippocrates I.

8. Gnosidicus

16. Nebrus

32. Sostratus III.

64. Theodorus II.

128. Sostratus, II.

256. Thedorus

512. Cleomyttades

1024. Crisamis

2048. Dardanus

4096. Sostatus

8192. Hippolochus

16384. Podalirius

32768. Asklepius

Namesakes

Some clinical symptoms and signs have been named after Hippocrates as he is believed to be the first person to describe those. Hippocratic face is the change produced in the countenance by death, or long sickness, excessive evacuations, excessive hunger, and the like. Clubbing, a deformity of the fingers and fingernails, is also known as Hippocratic fingers. Hippocratic succussion is the internal splashing noise of hydropneumothorax or pyopneumothorax. Hippocratic bench (a device which uses tension to aid in setting bones) and Hippocratic cap-shaped bandage are two devices named after Hippocrates. Hippocratic Corpus and Hippocratic Oath are also his namesakes. The drink hypocras is also believed to be invented by Hippocrates. Risus sardonicus, a sustained spasming of the face muscles may also be termed the Hippocratic Smile.

In the modern age, a lunar crater has been named Hippocrates. The Hippocratic Museum, a museum on the Greek island of Kos is dedicated to him. The Hippocrates Project is a program of the New York University Medical Center to enhance education through use of technology. Project Hippocrates (an acronym of "HIgh PerfOrmance Computing for Robot-AssisTEd Surgery") is an effort of the Carnegie Mellon School of Computer Science and Shadyside Medical Center, "to develop advanced planning, simulation, and execution technologies for the next generation of computer-assisted surgical robots." Both the Canadian Hippocratic Registry and American Hippocratic Registry are organizations of physicians who uphold the principles of the original Hippocratic Oath as inviolable through changing social times.

Dictionnaire historique

de la médecine ancienne et moderne

par Nicolas François Joseph Eloy

Mons – 1778

Osteopatia

ipertrofizzante pneumica

Malattia di Pierre-Marie

Dita

ippocratiche

Dita a bacchetta di tamburo con unghie a vetrino d'orologio

Ingrossamento delle ossa degli arti, e precisamente della parte superficiale di esse, o periostio. La manifestazione più evidente e caratteristica di questa affezione è rappresentata dalle cosiddette dita a bacchetta di tamburo, o dita ippocratiche, cioè ingrossate a clava nell'ultima falange, con incurvamento delle unghie a vetrino d'orologio. Di solito questa affezione si accompagna a malformazioni congenite di cuore, a vizi valvolari cardiaci, a malattie broncopolmonari croniche quali per esempio le bronchiectasie o l'ascesso polmonare. La terapia deve essere indirizzata a combattere la malattia polmonare o cardiaca in atto. Il meccanismo d'insorgenza di questo fenomeno patologico non è stato ancora oggi del tutto chiarito, ma probabilmente consiste in un aumentato afflusso di sangue nei vasi capillari delle dita, che spiegherebbe l'ipertrofia dei tessuti.

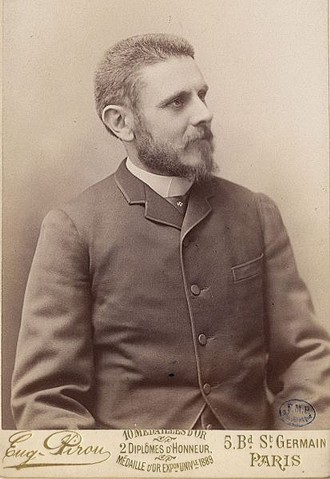

Pierre Marie

Medico francese (Parigi 1853 - Cannes 1940). Formatosi alla scuola del neuropsichiatra francese Jean Martin Charcot (Parigi 1825 - lago di Settons, Nièvre, 1893)., si è occupato essenzialmente di neurologia. Descrisse numerose malattie, fra le quali l'acromegalia (sindrome di Marie), l'atassia cerebellare ereditaria (malattia o atassia di Marie), l'osteopatia ipertrofizzante pneumica (sindrome di Marie-Bamberger, 1890), l'atrofia progressiva dei muscoli peronei (malattia di Charcot-Marie-Tooth), il diabete levulosurico. Portano il suo nome anche alcuni segni clinici, per es. la mano succulenta di Marie. Scrisse: Leçons sur les maladies de la moelle épinière (1892) e Leçons de clinique médicale (1896).

Hypertrophic

pulmonary osteoarthropathy

Marie-Bamberger disease

Clubbing

of fingers in a patient with Eisenmenger's syndrome.

Clubbing was

first described by Hippocrates,

then

clubbing is also known as "Hippocratic fingers".

Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy (or Marie-Bamberger disease) is a medical condition combining clubbing and periostitis of the long bones of the upper and lower extremities. Distal expansion of the long bones as well as painful, swollen joints and synovial villous proliferation are often seen. The condition may be primary or secondary to diseases like lung cancer. It is also known as "osteoarthropathia hypertrophicans". It is named for Eugen von Bamberger and Pierre Marie.

Pierre Marie (born 9 September 1853, died 13 April 1940) was a French neurologist who was a native of Paris. After finishing medical school, he became an interne in 1878, where he was an assistant to the famous neurologist Jean Martin Charcot (1825-1893) at the Salpêtrière and Bicêtre Hospitals. In 1883 he received his medical doctorate with a graduate thesis on Basedow’s disease, and in 1888 was promoted to Médecin des hôpitaux in Paris. In 1907 he attained the chair of pathological anatomy at the Faculty of Medicine, and in 1917 was appointed to the chair of neurology, a position he held until 1925. In 1911 Marie became a member of the Académie de Médecine.

One of Marie's earlier contributions was a description of a disorder of the pituitary gland known as acromegaly. His analysis of the disease was an important contribution in the emerging field of endocrinology. Marie is also credited as the first to describe pulmonary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy, cleidocranial dysostosis and rhizomelic spondylosis. In his extensive research of aphasia, his views concerning language disorders sharply contrasted the generally accepted views of Paul Broca (1824-1880). In 1907, he was the first person to describe the speech production disorder of foreign accent syndrome.

Marie was the first general secretary of the Société Française de Neurologie and with Edouard Brissaud (1852-1909) he was co-founder of the journal Revue neurologique. His name is associated with the eponymous Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease; which is named along with Jean-Martin Charcot and Howard Henry Tooth (1856-1925). This disease is characterized by gradual progressive loss of muscle tissue in the legs, arms and feet. It is considered one of the more common hereditary neurological diseases. Associated eponyms:

Marie's

ataxia: an hereditary disease of the nervous system, with cerebellar ataxia.

Marie-Foix-Alajouanine syndrome: cerebellar ataxia of the cerebellum in the

elderly; usually due to alcohol abuse. Named along with neurologists Théophile

Alajouanine (1890-1980) and Charles Foix (1882-1927).

Marie's anarthria: inability to articulate words due to cerebral lesions.

Marie–Strümpel Disease: also known as Ankylosing spondylitis; a severe arthritic spinal deformity. Named along with German neurologist Adolph Strümpell (1853-1925). The disease is sometimes referred to as "Bekhterev Disease"; named after Russian neurophysiologist Vladimir Bekhterev (1857-1927).

Marie-Léri syndrome: hand deformity caused by osteolysis of the articular surfaces of the fingers. Named with neurologist André Léri (1875-1930).

Pierre Marie né le 9 novembre 1853 à Paris et mort le 14 avril 1940 à Cannes est un médecin neurologue français. Il est à l'origine de la découverte de plusieurs entités cliniques nouvelles comme l'atrophie musculaire progressive en 1886, l'acromégalie en 1886, l'ostéoartropathie hypertrophique « pneumique » en 1890, l'hérédoataxie cérébelleuse en 1893, la spondylarthrite ankylosante (sous le nom de « spondylose rhizomélique ») en 1898, ce qui lui vaut une réputation internationale. À la clinique neurologique de la Salpêtrière, il succède en 1917 à Dejerine à la Chaire inaugurée par Jean-Martin Charcot.

Après ses études de médecine, il est nommé interne des hôpitaux de Paris en 1878 et commence à étudier la neurologie sous la tutelle de Jean-Martin Charcot à la Salpêtrière et à Bicêtre. Pierre Marie est l'un des étudiants les plus remarquables de Charcot dont il devient l'assistant spécial et le chef de son laboratoire. Il obtînt son doctorat en médecine en 1883 avec une thèse sur une maladie thyroïdienne, la maladie de Basedow. Il obtient son agrégation à la Faculté de Médecine de Paris en 1889 où il a présenté une série de conférences célèbres sur les maladies de la moelle épinière.

Entre 1885 et 1910, période la plus productive de sa carrière, il a écrit des nombreux articles et livres et a développé une école internationale de neurologie. Marie a identifié avec succès et a décrit une série de désordres auxquels son nom est lié. En 1886, il décrit l'acromégalie, une maladie qui portera plus tard son nom (maladie de Pierre Marie). L'analyse qu'il fait à cette occasion des désordre de l'hypophyse contribue de façon déterminante au domaine naissant de l'endocrinologie.

En 1897 il a créé un service neurologique à Bicêtre qui a rapidement eu une réputation mondiale. Ses travaux sur l'aphasie l'ont opposé à Paul Broca (1824-1880) et Carl Wernicke (1848-1905) quant à la localisation du centre de la parole. En 1907 il a sollicité avec succès la chaire vacante d'anatomie pathologique à la Faculté de Médecine et, avec l'aide de Gustave Roussy, son successeur, Marie a complètement modernisé l'enseignement d'anatomie pathologique.

En collaboration avec Charles Foix, Henry Meige et d'autres, il publia différents travaux consacrés aux séquelles neurologiques de la guerre. En 1917, âgé 64, Marie a été nommé à la chaire de neurologie qui avait été créée pour Charcot et occupée depuis par Fulgence Raymond (1844-1919), Édouard Brissaud (1852-1909) et Joseph Jules Dejerine (1849-1917). Avec Édouard Brissaud, il a fondé la Revue de Neurologie en 1893, et la Société Française de Neurologie dont il fut le premier secrétaire général. Il a été nommé membre de l'Académie de médecine en 1911.

Dita

ippocratiche

Dita a bacchetta di tamburo con unghie a vetrino d'orologio

Condizione di ipertensione arteriosa polmonare conseguente a cardiopatia o vasculopatia congenita, in cui lo shunt sinistra-destra si inverte e compare cianosi, accompagnata da dispnea, dolore stenocardico, emottisi ed epistassi, sincope e cefalea. Può essere complicata da insufficienza cardiaca congestizia, aritmie, infarti miocardici e polmonari. Insorge dopo i 2 anni di età, in media verso i 14 anni, e conduce a morte entro i 30-35 anni. Tuttavia le persone affette conducono una vita pressoché normale fino alla morte, che è di solito improvvisa. Sono fattori di rischio per un aggravamento della sindrome emorragie, febbre, vomito e diarrea, gravidanza e puerperio. La terapia consiste nel porre particolare attenzione a questi fattori di rischio e, poiché è in genere controindicato l'intervento chirurgico, l'orientamento è quello di evitare che insorga la sindrome, operando tutti i bambini con comunicazione sistemico-polmonare. Nell'adulto si può intervenire solo col trapianto cuore-polmoni. Fu descritta nel 1897 dal Dr Victor Eisenmenger (Vienna 1864-1932).

Clubbing

of fingers in a patient with Eisenmenger's syndrome.

Clubbing was

first described by Hippocrates,

then

clubbing is also known as "Hippocratic fingers".

Eisenmenger's syndrome (or Eisenmenger's reaction) is defined as the process in which a left-to-right shunt caused by a ventricular septal defect in the heart causes increased flow through the pulmonary vasculature, causing pulmonary hypertension, which in turn, causes increased pressures in the right side of the heart and reversal of the shunt into a right-to-left shunt. It can cause serious complications in pregnancy, though successful delivery has been reported.

Conditions needed for a person to be diagnosed with Eisenmenger's Syndrome are:

- an underlying heart defect that allows blood to pass between the left and right sides of the heart.

- pulmonary hypertension, or elevated blood pressure in the lungs

- polycythemia, an increase in the number of red blood cells

- the reversal of the shunt.

Eisenmenger's syndrome was so named by Dr. Paul Hamilton Wood (London 1907-1962) after Dr. Victor Eisenmenger (Vienna 1864-1932), who first described the condition in 1897.

A number of congenital heart defects can cause Eisenmenger's syndrome, including atrial septal defects, ventricular septal defects, patent ductus arteriosus, and more complex types of acyanotic heart disease. The left side of the heart supplies blood to the whole body, and as a result has higher pressures than the right side, which supplies only deoxygenated blood to the lungs. If a large anatomic defect exists between the sides of the heart, blood will flow from the left side to the right side. This results in high blood flow and pressure travelling through the lungs. The increased pressure causes damage to delicate capillaries, which then are replaced with scar tissue. Scar tissue does not contribute to oxygen transfer, therefore decreasing the useful volume of the pulmonary vasculature. The scar tissue also provides less flexibility than normal lung tissue, causing further increases in blood pressure, and the heart must pump harder to continue supplying the lungs, leading to damage of more capillaries.

The reduction in oxygen transfer reduces oxygen saturation in the blood, leading to increased production of red blood cells in an attempt to bring the oxygen saturation up. The excess of red blood cells is called polycythemia. Desperate for enough circulating oxygen, the body begins to dump immature red cells into the blood stream. Immature red cells are not as efficient at carrying oxygen as mature red cells, and they are less flexible, less able to easily squeeze through tiny capillaries in the lungs, and so contribute to death of pulmonary capillary beds. The increase in red blood cells also causes hyperviscosity syndrome.

A person with Eisenmenger's Syndrome is paradoxically subject to the possibility of both uncontrolled bleeding due to damaged capillaries and high pressure, and random clots due to hyperviscosity and stasis of blood. The rough places in the heart lining at the site of the septal defects/shunts tend to gather platelets and keep them out of circulation, and may be the source of random clots. Eventually, due to increased resistance, pulmonary pressures may increase sufficiently to cause a reversal of blood flow, so blood begins to travel from the right side of the heart to the left side, and the body is supplied with deoxygenated blood, leading to cyanosis and resultant organ damage.

In early childhood, surgical intervention can repair the heart defect, preventing most of the pathogenesis of Eisenmenger's syndrome. If treatment has not taken place, heart-lung transplant is required to fully treat the syndrome. If this option is not available, treatment is mostly palliative, using pulmonary vasodilators such as bosentan, antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent endocarditis, phlebotomy to treat polycythemia, and maintaining proper fluid balance. These measures can prolong lifespan and improve quality of life. Anticoagulants should rarely if ever be administered to a patient with Eisenmenger's syndrome due to the fact that they generally have a prolonged aPTT, PT, decreased coagulation factors, decreased platelet counts and abnormal platelet function. If anticoagulants are administered, the INR should be kept on the low side of the therapeutic range.