Lessico

Pausania

detto il Periegeta

In greco periëgëtës con l'accento sulla ultima ë significa colui che

va in giro, gironzolone, derivato dal verbo periágø = andare in giro.

Scrittore

greco della metà del secolo II dC. Nativo forse della Lidia![]() , visitò la

Palestina, l'Arabia, l'Egitto, l'Italia e soprattutto la Grecia, della quale

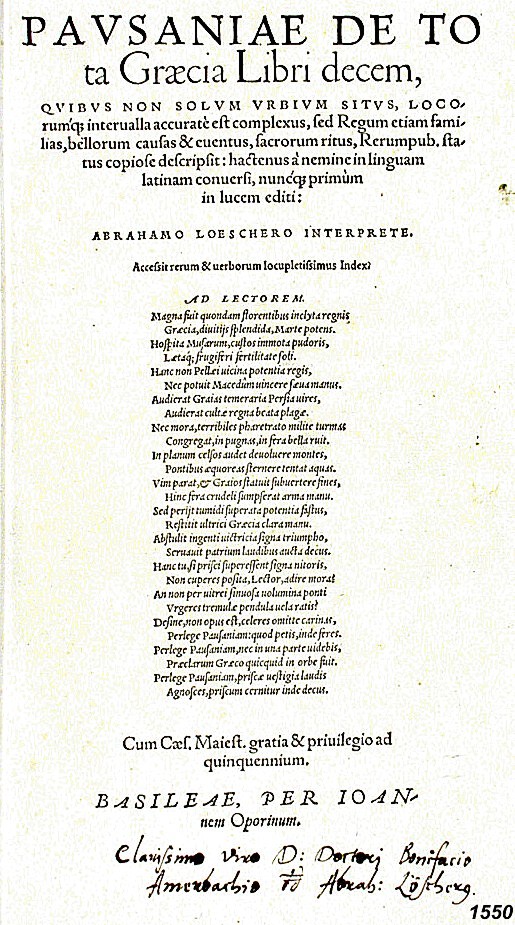

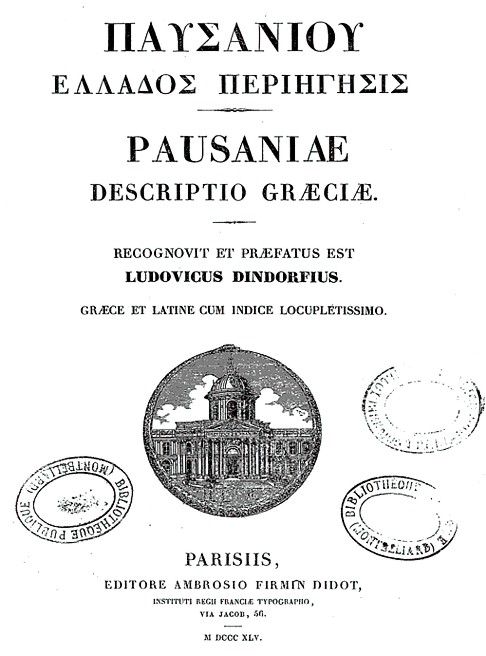

lasciò una descrizione sistematica nell'opera in 10 libri Periegesi della

Grecia.

, visitò la

Palestina, l'Arabia, l'Egitto, l'Italia e soprattutto la Grecia, della quale

lasciò una descrizione sistematica nell'opera in 10 libri Periegesi della

Grecia.

La materia è ordinata per regioni e le notizie fornite riguardano la storia, la topografia, i monumenti, i culti di ognuna di esse. Oltre che di grande interesse, la Periegesi è, per la ricchezza e l'accuratezza della documentazione sui monumenti e le opere d'arte, fondamentale ai fini della nostra conoscenza della Grecia classica e di età imperiale.

Nonostante l'autore registri a volte notizie leggendarie o errate, la sostanziale veridicità del suo racconto è stata accertata dalle ricerche archeologiche. Pausania predilige in scultura – e ciò spiega alcune lacune nella sua esposizione – le opere della scuola attica, dimostrando poca comprensione, come del resto i suoi contemporanei, sia per l'arcaismo (che apprezza invece in architettura) sia per l'età ellenistica.

Pausania il Periegeta

Pausania il Periegeta (110 – 180 circa) è stato uno scrittore e geografo greco, d'origine asiatica vissuto intorno al II secolo dC. Forse è lo stesso Pausania di Damasco e il Pausania sofista vissuto anche a Roma. Notizie relative a Pausania sono assai difficili da reperire se non attraverso pochi accenni che si possono trovare nella sua opera. Si ipotizza che sia vissuto sotto gli Antonini, dal momento che cita ed esalta le opere urbanistiche in Grecia di Adriano (117-138) e il regno di Antonino Pio (138-161) e Marco Aurelio (161-180) dal 117 al 180.

Circa la sua provenienza, è stata proposta l'identificazione di Pausania con un omonimo sofista di Magnesia, in Lidia (Habicht), ma senza prove inoppugnabili: sull'origine micrasiatica di Pausania provano l'ammirazione attribuita a Erodoto e l'attenzione per la storia delle colonie greche d'Asia Minore. Altro cenno per la datazione dell'autore è dato dall'invasione dei barbari Costoboci, databile attorno al 170, che distrussero il tempio di Demetra a Eleusi, perno centrale della restaurazione filoellenica degli Antonini. La data di morte di Pausania viene posta intorno al 180, dal momento che l'autore non accenna all'ascesa al trono di Commodo, cosa difficilmente spiegabile se vi avesse assistito.

La sua opera, in dieci libri, s'intitola Periegesi della Grecia (Hellàdos Perièghesis). Per periegesi s'intende quel filone storiografico, soprattutto di epoca ellenistica, che, intorno a un itinerario geografico, raccoglie notizie storiche su popoli, persone e località, verificate, per quanto possibile, dall'esperienza diretta. Ogni libro dell'opera descrive, fatta eccezione per l’Eubea e la Tessaglia, una regione della Grecia antica, con excursus storici e geografici intesi ad informare su fatti d’importanza secondaria, presupponendo la conoscenza delle opere storiche maggiori, quali quelle di Tucidide ed Erodoto.

Periegesi della Grecia

libro

I – Attica

libro II – Corinto

libro III – Laconia

libro IV – Messenia

libro V – Elide 1

Libro VI – Elide 2

libro VII – Acaia

libro VIII – Arcadia

libro IX – Beozia

libro X – Focide e Locride

La prosa di Pausania è quella attica e arieggia la semplicità erodotea. Il valore e l'attendibilità storici dell'opera sono immensi, soprattutto quando descrive siti non altrimenti descritti. A confronto con fonti più accurate, specie quando riferisce episodi storici o tratta di monumenti largamente noti, il suo valore è modesto, considerata l'imprecisione e le fonti indirette cui l'autore ricorre. Ha anche l'irritante abitudine di rifiutarsi di descrivere alcuni edifici o cerimonie quando queste descrizioni gli sembrino in contrasto con le proprie (o altrui) convinzioni religiose.

Pausanias was a Greek traveller and geographer of the 2nd century CE, who lived in the times of Hadrian, Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius. He is famous for his Description of Greece, a lengthy work that describes ancient Greece from firsthand observations, and is a crucial link between classical literature and modern archaeology. This is how Andrew Stewart assesses him:

A careful, pedestrian writer, he is interested not only in the grandiose or the exquisite but in unusual sights and obscure ritual. He is occasionally careless, or makes unwarranted inferences, and his guides or even his own notes sometimes mislead him; yet his honesty is unquestionable, and his value without par.

Pausanias was probably a native of Lydia; he was certainly familiar with the western coast of Asia Minor, but his travels extended far beyond the limits of Ionia. Before visiting Greece he had been to Antioch, Joppa and Jerusalem, and to the banks of the River Jordan. In Egypt he had seen the Pyramids, while at the temple of Ammon he had been shown the hymn once sent to that shrine by Pindar. In Macedonia he had almost certainly viewed the traditional tomb of Orpheus. Crossing over to Italy, he had seen something of the cities of Campania and of the wonders of Rome. He was one of the first to write of seeing the ruins of Troy, Alexandria Troas, and Mycenae.

Pausanias' Description of Greece is in ten books, each dedicated to some portion of Greece. He begins his tour in Attica, where the city of Athens and its demes dominate the discussion. Subsequent books describe Corinth, Laconia, Messenia, Elis, Achaia, Arcadia, Boetia, Phocis and Ozolian Locris. The project is more than topographical; it is a cultural geography. Pausanias digresses from description of architectural and artistic objects to review the mythological and historical underpinnings of the society that produced them. As a Greek writing under the auspices of the Roman empire, he found himself in an awkward cultural space, between the glories of the Greek past he was so keen to describe and the realities of a Greece beholden to Rome as a dominating imperial force. His work bears the marks of his attempt to navigate that space and establish an identity for Roman Greece.

He is not a naturalist by any means, though he does from time to time comment on the physical realities of the Greek landscape. He notices the pine trees on the sandy coast of Elis, the deer and the wild boars in the oak woods of Phelloe, and the crows amid the giant oak trees of Alalcomenae. It is mainly in the last section that Pausanias touches on the products of nature, such as the wild strawberries of Helicon, the date palms of Aulis, and the olive oil of Tithorea, as well as the tortoises of Arcadia and the "white blackbirds" of Cyllene.

Pausanias is most at home in describing the religious art and architecture of Olympia and of Delphi. Yet, even in the most secluded regions of Greece, he is fascinated by all kinds of quaint and primitive images of the gods, holy relics, and many other sacred and mysterious objects. At Thebes he views the shields of those who died at the Battle of Leuctra, the ruins of the house of Pindar, and the statues of Hesiod, Arion, Thamyris, and Orpheus in the grove of the Muses on Helicon, as well as the portraits of Corinna at Tanagra and of Polybius in the cities of Arcadia. Pausanias has the instincts of an antiquary. As his editor Christian Habicht has said:

"In general he prefers the old to the new, the sacred to the profane; there is much more about classical than about contemporary Greek art, more about temples, altars and images of the gods, than about public buildings and statues of politicians. Some magnificent and dominating structures, such as the Stoa of King Attalus in the Athenian Agora (rebuilt by Homer Thompson) or the Exedra of Herodes Atticus at Olympia are not even mentioned."

Pausanias' Periegesis, unlike a Baedeker guide, stops for a brief excursus on a point of ancient ritual or to tell an apposite myth, in a genre that would not become popular again until the early nineteenth century. In the topographical part of his work, Pausanias is fond of digressions on the wonders of nature, the signs that herald the approach of an earthquake, the phenomena of the tides, the ice-bound seas of the north, and the noonday sun which at the summer solstice casts no shadow at Syene (Aswan). While he never doubts the existence of the gods and heroes, he sometimes criticizes the myths and legends relating to them. His descriptions of monuments of art are plain and unadorned. They bear the impression of reality, and their accuracy is confirmed by the extant remains. He is perfectly frank in his confessions of ignorance. When he quotes a book at second hand he takes pains to say so.

The work, all ten volumes of it, was a failure. "It was not read," Habicht relates — "there is not a single mention of the author, not a single quotation from it, not a whisper before Stephanus Byzantius in the sixth century, and only two or three references to it throughout the Middle Ages". We came perilously close to losing it altogether, in fact: the only manuscripts of Pausanias are fifteenth-century copies, full of errors and lacunae. Until twentieth-century archaeologists found that Pausanias was a reliable guide to the sites they were excavating, Pausanias was largely dismissed by nineteenth- and early twentieth-century classicists of a purely literary bent, who followed the authoritative Wilamowitz in discrediting him, as a purveyor of literature quoted at second-hand, who, it was suggested, had not actually visited most of the places he described. The experience of a century of archaeologists has fully vindicated him.

Artistic representation of the Statue of Zeus in Olympia around 16th century, actually quite inexact: according to Pausanias (V, 11, 1f), Zeus carried a statuette of Victory in his right hand and a sceptre with a bird sitting on it in the left hand.Four victories stood at each foot of the throne and two at the base of each foot.

Pausanias, dit le Périégète, né (probablement) à Magnésie du Sipyle en Lydie vers 115 et mort à Rome vers 180, est un géographe et voyageur de l'Antiquité. Pausanias explore la Grèce, la Macédoine, l'Italie, l'Asie et l'Afrique avant de se fixer à Rome vers 174. Là, il écrit une Description de la Grèce ou Périégèse en 10 livres. À la manière d'un guide de voyage moderne, il donne, au fur et à mesure de son itinéraire, la liste détaillée des sites qu'il visite et les légendes qui s'y rapportent. Mieux, pour l'historien Paul Veyne (Les Grecs ont-ils cru à leurs mythes?, 1983):

« Pausanias est l'égal d'un philologue ou d'un archéologue allemand de la grande époque; pour décrire les monuments et raconter l'histoire des différentes contrées de la Grèce, il a fouillé les bibliothèques, a beaucoup voyagé, a tout vu de ses yeux. (...) La précision des indications et l'ampleur de l'information surprennent, ainsi que la sûreté du coup d'œil. »

Son œuvre est ainsi un témoignage de première importance sur la Grèce à l'époque romaine, en particulier pour le IIe siècle de l'ère chrétienne, même si Pausanias se complaît souvent à mêler histoire et mythologie. De nombreuses fouilles archéologiques ont confirmé à maintes reprises la véracité de ses informations, surtout en ce qui concerne les sites historiques et les œuvres d'art qu'ils contenaient. La Description se décompose comme suit:

livre I

l'Attique et Mégare

livre II Corinthe, l'Argolide, ainsi qu'Égine et les îles alentour

livre III la Laconie

livre IV la Messénie

livre V l'Élide et Olympie

livre VI l'Élide (2e partie)

livre VII Achaïe

livre VIII Arcadie

livre IX Béotie

livre X la Phocide et la Locride