Lessico

Riccio di mare

Echinoidei

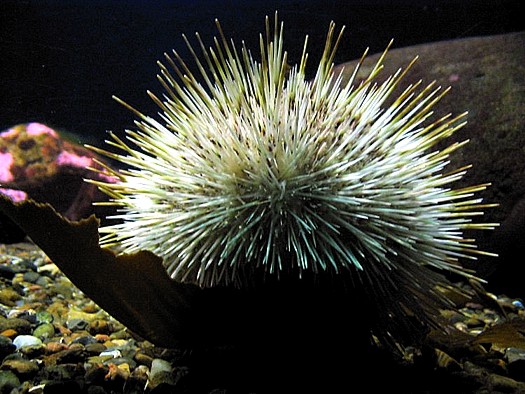

La classe Echinoidea fa parte del phylum Echinodermata e comprende gli organismi marini comunemente denominati ricci di mare, dal corpo generalmente a forma globosa più o meno sferoidale, anche se esistono specie appiattite o discoidali. Il termine Echinoidea deriva dal greco echînos che significa riccio, porcospino.

Tra le specie più comuni nel Mediterraneo vanno ricordate:

Paracentrotus lividus (Echinidae), volgarmente noto come riccio femmina

Arbacia lixula (Arbaciidae), volgarmente noto come riccio maschio

Sphaerechinus granularis (Toxopneustidae), riccio di prateria o riccio regina

Spatangus purpureus (Spatangidae)

Gli Echinoidei possiedono in genere un dermascheletro rigido formato da piastre di natura calcarea unite in modo rigido fra loro (in alcuni ricci, specie nelle forme che vivono in acque abissali, le piastre sono libere e il dermascheletro risulta flessibile). Caratteristica degli Echinoidei è la presenza di aculei che ricoprono la superficie esterna e che sono mobili e variabili sia come numero sia come forma e dimensioni. Esistono infatti ricci di mare con aculei molto corti e molto numerosi che ricoprono fittamente il corpo; altri invece possiedono grossi aculei radi e molto resistenti; altri infine, soprattutto le specie che vivono su fondi sabbiosi, possiedono piccoli aculei sottilissimi che formano una specie di peluria.

Negli Echinoidei Regolari, in posizione radiale e secondo linee meridiane, fuoriescono dalla parete del corpo i pedicelli ambulacrali, che terminano con una ventosa. Questi, negli Irregolari, sono riuniti in posizione orale e aborale a formare aree distinte. Sono essenzialmente organi di adesione e di locomozione.

Gli Echinoidei vivono a tutte le profondità, da pochi centimetri fino agli abissi e praticamente sono diffusi in tutti i mari del mondo. La loro anatomia interna è fondamentalmente simile allo schema tipico degli Echinodermi; caratteristica è la presenza di un apparato masticatore, la “lanterna di Aristotele” (Historia animalium IV,5), molto sviluppato negli Echinoidei Regolari, ridotto o mancante negli Irregolari: è costituito da cinque denti portati da formazioni scheletriche mosse da muscoli che si inseriscono su sporgenze interne delle piastre ambulacrali che circondano l'apertura boccale. La forma larvale degli Echinoidei è l'echinopluteus che, al termine del suo sviluppo, si trasforma in un giovane di un 1 mm di diametro.

Gli Echinoidei comprendono le sottoclassi Regolari e Irregolari. I primi Echinoidei Regolari apparvero nell'Ordoviciano derivando, forse, dai Cistoidi. Tuttavia, tutte le caratteristiche dei veri Echinoidei furono raggiunte solo nel Carbonifero durante il quale sono presenti grandi Echinoidei Regolari della sottoclasse Periscoechinoidei: i Paleoechinidi.

Con la grande estinzione del Permiano, solo il genere Miocidaris sopravvive e valica il limite Paleozoico-Mesozoico. L'intero futuro degli Echinoidei risiede in quest'unico genere, che nel Triassico inferiore diede origine alle forme dell'ordine Cidaroidi. Questi ultimi, con una grande radiazione adattativa diedero origine a tutti gli ordini di Echinoidei mesozoici, fossili e viventi, oggi noti. Da questo periodo i Regolari subirono una lenta evoluzione mentre gli Irregolari, comparsi nel Giurassico inferiore, effettuarono evoluzioni che portarono notevoli cambiamenti nella struttura esterna dell'animale.

Strongylocentrotus purpuratus

Sea urchins in California tide pools

Sea urchins are small, globular, spiny sea creatures, composing most of class Echinoidea. They are found in oceans all over the world. Their shell, or "test", is round and spiny, typically from 3 to 10 cm across. Common colors include black and dull shades of green, olive, brown, purple, and red. They move slowly, feeding mostly on algae. Otters, wolf eels, and other predators feed on urchins. Sea urchins are harvested and served as a delicacy.

Sea urchins have adhesive tube feet

Sea urchins are members of the phylum Echinodermata, which also includes starfish, sea cucumbers, brittle stars, and crinoids. Like other echinoderms they have fivefold symmetry (called pentamerism) and move by means of hundreds of tiny, transparent, adhesive "tube feet". The pentamerous symmetry is not obvious at a casual glance but is easily seen in the dried shell or test of the urchin.

Together with sea cucumbers (Holothuroidea), they make up the subphylum Echinozoa, which is defined by primarily having a globoid shape without arms or projecting rays. Sea cucumbers and the irregular echinoids have secondarily evolved different shapes. Although many sea cucumbers have branched tentacles surrounding the oral opening, these have originated from modified tube feet and are not homologous to the arms of the crinoids, starfish and brittle stars.

Classification and nomenclature

Within the echinoderms, sea urchins are classified as echinoids (class Echinoidea). Specifically, the term "sea urchin" refers to the "regular echinoids," which are symmetrical and globular. The ordinary phrase "sea urchin" actually includes several different taxonomic groups: the Echinoida and the Cidaroida or "slate-pencil urchins", which have very thick, blunt spines, and others. Besides sea urchins, the Echinoidea also includes three groups of "irregular" echinoids: flattened sand dollars, sea biscuits, and heart urchins. The name urchin is an old name for the round spiny hedgehogs that sea urchins resemble.

Physiology

At first glance, a sea urchin often appears sessile, i.e. incapable of moving. Sometimes the most visible sign of life is the spines, which are attached at their bases to ball-and-socket joints and can be pointed in any direction. In most urchins, a light touch elicits a prompt and visible reaction from the spines, which converge toward the point that has been touched. A sea urchin has no visible eyes, legs, or means of propulsion, but it can move freely over surfaces by means of its adhesive tube feet, working in conjunction with its spines.

On the oral surface of the sea urchin is a centrally located mouth made up of five united calcium carbonate teeth or jaws, with a fleshy tongue-like structure within. The entire chewing organ is known as Aristotle's lantern, which name comes from Aristotle's accurate description in his History of Animals IV,5:

"…the urchin has what we mainly call its head and mouth down below, and a place for the issue of the residuum up above. The urchin has, also, five hollow teeth inside, and in the middle of these teeth a fleshy substance serving the office of a tongue. Next to this comes the esophagus, and then the stomach, divided into five parts, and filled with excretion, all the five parts uniting at the anal vent, where the shell is perforated for an outlet... In reality the mouth-apparatus of the urchin is continuous from one end to the other, but to outward appearance it is not so, but looks like a horn lantern with the panes of horn left out." (tr. D'Arcy Thompson)

The spines, which in some species are long and sharp, serve to protect the urchin from predators. The spines can inflict a painful wound on a human who steps on one, but they are not seriously dangerous, and it is not clear that the spines are truly venomous (unlike the pedicellariae between the spines, which are venomous).

Typical sea urchins have spines that are 1 to 3 cm in length, 1 to 2 mm thick, and not terribly sharp. Diadema antillarum, familiar in the Caribbean, has thin, potentially dangerous spines that can be 10 to 20 cm long.

Diet

Echinothrix

calamaris, a species of sea urchin.

The sphere in the middle of a sea urchin is its anus.

Sea urchins feed mainly on algae, but can also feed on a wide range of invertebrates such as mussels, sponges, brittle stars and crinoids. Sea urchin is one of the favorite foods of sea otters and are also the main source of nutrition for wolf eels. Left unchecked, urchins will devastate their environment, creating what biologists call an urchin barren, devoid of macroalgae and associated fauna. Where sea otters have been re-introduced into British Columbia, the health of the coastal ecosystem has improved dramatically.

Geologic history

Fossil

sea urchin Lovenia woodsi

from the Pliocene of Australia

The earliest known echinoids are found in the rock of the upper part of the Ordovician period (c 450 MYA), and they have survived to the present day, where they are a successful and diverse group of organisms. In well-preserved specimens the spines may be present, but usually only the test is found. Sometimes isolated spines are common as fossils. Some echinoids (such as Tylocidaris clavigera, which is found in the Cretaceous period Chalk Formation of England) had very heavy club-shaped spines that would be difficult for an attacking predator to break through and make the echinoid awkward to handle. Such spines are also good for walking on the soft sea-floor.

Complete fossil echinoids from the Paleozoic era are generally rare, usually consisting of isolated spines and small clusters of scattered plates from crushed individuals. Most specimens occur in rocks from the Devonian and Carboniferous periods. The shallow water limestones from the Ordovician and Silurian periods of Estonia are famous for the echinoids found there. The Paleozoic echinoids probably inhabited relatively quiet waters. Because of their thin test, they would certainly not have survived in the turbulent wave-battered coastal waters inhabited by many modern echinoids today.

During the upper part of the Carboniferous period, there was a marked decline in echinoid diversity, and this trend continued into the Permian period. They neared extinction at the end of the Paleozoic era, with just six species known from the Permian period. Only two separate lineages survived the massive extinction of this period and into the Triassic: the genus Miocidaris, which gave rise to the modern cidaroids (pencil urchins), and the ancestor that gave rise to the euechinoids. By the upper part of the Triassic period, their numbers began to increase again. The cidaroids have changed very little since their modern design was established in the Late Triassic and are today considered more or less as living fossils.

The euechinoids, on the other hand, diversified into new lineages throughout the Jurassic period and into the Cretaceous period, and from them emerged the first irregular echinoids (superorder Atelostomata) during the early Jurassic, and when including the other superorder (Gnathostomata) or irregular urchins which evolved independently later, they now represent 47% of all present species of echinoids thanks to their adaptive breakthroughs in both habit and feeding strategy, which allowed them to exploit habitats and food sources unavailable to regular echinoids. During the Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras the echinoids flourished. While most echinoid fossils are restricted to certain localities and formations, where they do occur, they are quite often abundant. An example of this is Enallaster, which may be collected by the thousands in certain outcrops of limestone from the Cretaceous period in Texas. Many fossils of the Late Jurassic Plesiocidaris still have the spines attached.

Some

echinoids, such as Micraster which is found in the Cretaceous period

Chalk Formation of England and France, serve as zone or index fossils. Because

they evolved rapidly over time, such fossils are useful in enabling geologists

to date the rocks in which they are found. However, most echinoids are not

abundant enough and may be too limited in their geographic distribution to

serve as zone fossils.

In the early Tertiary (c 65 to 1.8 MYA), sand dollars (order Clypeasteroida)

arose. Their distinctive flattened test and tiny spines were adapted to life

on or under loose sand. They form the newest branch on the echinoid tree.

Culinary Usage/Fishery

Sea urchins are an important fishery and are harvested for food. Contrary to popular belief, the portion of the sea urchin sold and served as one of the ocean’s most opulent treasures is not the roe. It is the gonads of this hermaphrodite sea creature that are scooped out of the urchin’s spiny shell in five custard-like, golden sections. Known in Japan as "uni" and traditionally considered an aphrodisiac, gonads are the only edible part of the urchin.

Model Organism

Sea

urchins are one of the traditional model organisms in developmental biology.

The use of sea urchins in this context originates from the 1800's, when the

embryonic development of the sea urchins was noticed to be particularly easily

viewed by microscopy. Sea urchins were the first species in which the sperm

cells were proven to play an important role in reproduction by fertilizing the

ovum.

With the recent sequencing of the sea urchin genome, homology has been found

between sea urchin and vertebrate immune system-related genes. Sea urchins

code for at least 222 Toll-like receptor (TLR) genes and over 200 genes

related to the Nod-like-receptor (NLR) family found in vertebrates. This has

made the sea urchin a valuable model organism for immunologists to study the

evolution of innate immunity.

Les échinidés ou echinides (surnommés oursins, hérisson de mer ou châtaigne de mer) sont des organismes marins portant des piquants (non des épines) sur l'entièreté du corps.

La couleur de l'animal est très variable, elle peut être brune, noire, pourpre, verte, blanche, rouge ou multicolore. Beaucoup d'espèces présentent des tailles allant de 6 à 12 cm de diamètre, mais certaines espèces du Pacifique peuvent atteindre des diamètres de 36 cm. Comme le reste des membres du Phylum des échinodermes les oursins présentent un corps à structure dite pentamèrique (symétrie d'ordre 5). L'animal ne présente donc pas une face ventrale et dorsale mais une face aborale (anus) et un face orale (bouche). Chez les oursins dit réguliers la face aborale est située sur le dessus de l'animal et la face orale sur le dessous et directement en contact avec le substrat (oursins irréguliers). Le corps globuleux de l'animal peut être divisé en 10 sections radiaires qui convergent vers le pôle oral et le pôle aboral. On peut observer 5 sections portant des podia ou podions qui se nomment les zones ambulacraires.

Ce sont des invertébrés marins de l'embranchement des Echinodermata (Échinodermes), du grec ekhinos, « épine » et derma « derme ». Ils sont de proches parents des concombres de mer et des étoiles de mer. L'oursin (châtaigne des mers) commun du littoral européen se nomme Paracentrotus lividus.

Consommation d'oursin

Détail des oeufs d'un oursin prêt à la consommation.

Tous les oursins ne sont pas consommables. Avec des ciseaux pointus, on découpe à mi-hauteur la carapace, en partant de la zone molle dépourvue de piquants autour de la bouche. On consomme les cinq glandes sexuelles c'est-à-dire le corail et le liquide qui les entourent. Pour y avoir accès, il faut enlever la bouche et l'appareil digestif (la lanterne d'Aristote). On mange le corail cru. Suivant la saison, le corail est plus ou moins aggloméré et sa couleur va de verdâtre à rouge sombre. L'oursin est aussi appelé "oeuf de Mer " (Victor Hugo in "Les travailleurs de la mer").Ils sont consommés dans de nombreux pays du monde. La pêche et la vente sont interdites de mai à septembre en France

L'oursin et la recherche

L'oursin est un modèle très utilisé pour la recherche. Réaliser une fécondation en laboratoire est relativement simple. En écotoxicologie: les larves d'oursins (appelées pluteus, en forme de Tour Eiffel) présentent des difformités si les concentrations de polluants dans l'eau dépassent un certain seuil. De même, le pourcentage d'ovocytes fécondés diminue avec l'augmentation des polluants dans le milieu. On peut donc utiliser les oursins comme indicateurs de pollution du milieu. Les piquants des oursins peuvent aussi être analysés afin d'en analyser la biomécanique des les lieux les plus pollués.

En biologie cellulaire fondamentale et appliquée: une fois l'ovocyte fécondé, les divisions de la cellule-oeuf sont faciles à observer au microscope et sont synchronisées. La cellule-oeuf d'oursin est donc un outil idéal pour l'étude des mécanismes de division cellulaire et au-delà, des dérèglements qui peuvent conduire au développement de cancers.