Lessico

Stafisagria

Delphinium staphisagria

Dal greco staphís

agría, cioè, uva secca selvatica, che corrisponderebbe alla nostra

stafisagria, Delphinium staphisagria, appartenente alla Ranunculacee.

Si può presumere che venisse detta uva secca selvatica in quanto si usavano i

semi essiccati che sono di colore nerastro come gli acini dell'uva nera![]() .

.

Invece

l'uva sì selvatica, ma che non è secca, cioè la agría staphylë,

dovrebbe corrispondere a tutt'altra pianta, e precisamente alla Bryonia

alba![]() appartenente

alla famiglia delle Cucurbitacee.

appartenente

alla famiglia delle Cucurbitacee.

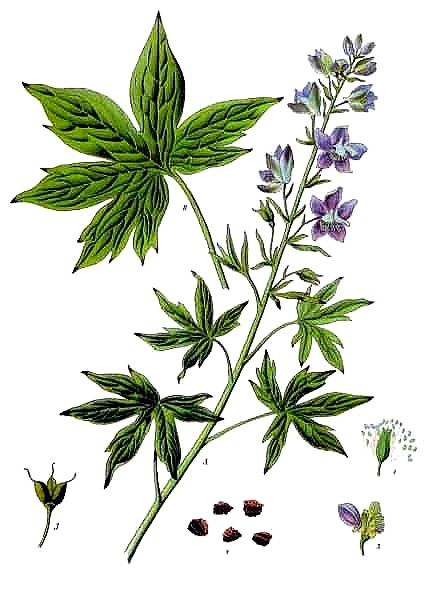

Delphinium staphisagria: pianta della famiglia Ranuncolacee diffusa nell'Europa meridionale. È un'erba annua ricoperta di peli ghiandolosi e vischiosi, con foglie alterne e fiori irregolari, violetti. I semi, che contengono diversi alcaloidi, vengono usati per la produzione di insetticidi.

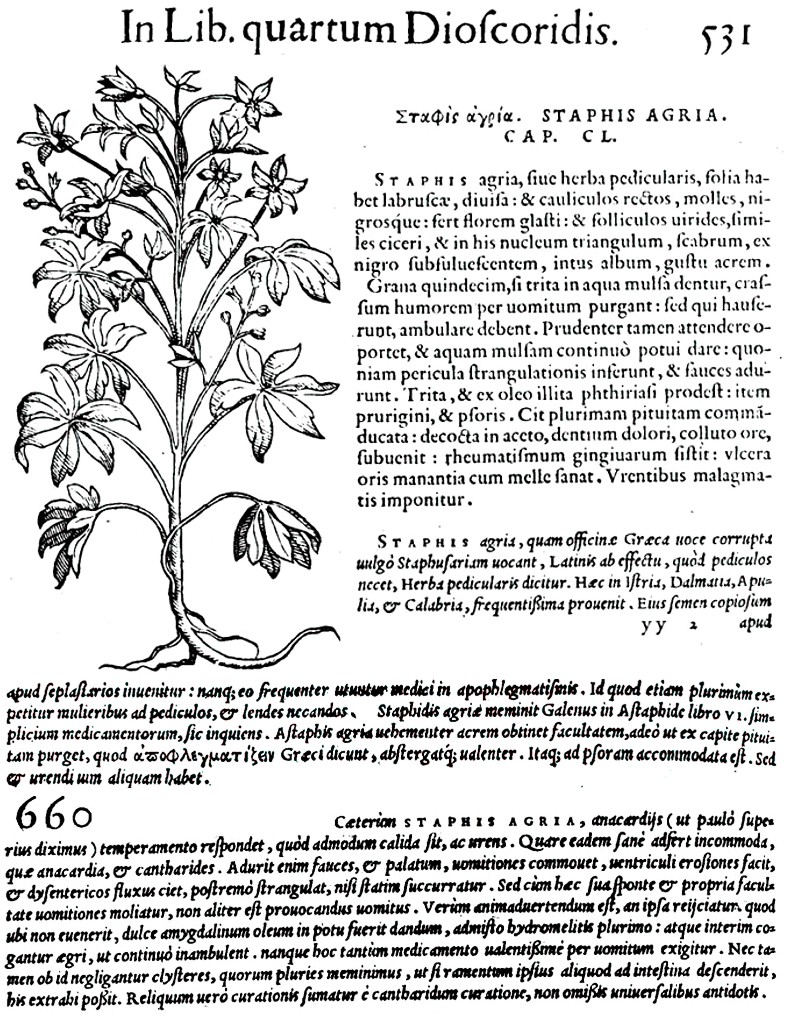

L'uso che

ne facevano gli antichi era contro i pidocchi, ma Galeno![]() - come

specifica Pierandrea Mattioli

- come

specifica Pierandrea Mattioli![]() nel suo

celebre Commentarii in libros sex Pedacii Dioscoridis Anazarbei De Materia

Medica (Venetiis,

apud Valgrisium, 1554

nel suo

celebre Commentarii in libros sex Pedacii Dioscoridis Anazarbei De Materia

Medica (Venetiis,

apud Valgrisium, 1554![]() ) –

usava la stafisagria contro la pituita

) –

usava la stafisagria contro la pituita![]() . Mattioli

si fa premura di proporre i rimedi contro gli effetti nocivi di questa pianta.

. Mattioli

si fa premura di proporre i rimedi contro gli effetti nocivi di questa pianta.

Delphinium is a genus of about 250 species of annual, biennial or perennial flowering plants in the buttercup family Ranunculaceae, native throughout the Northern Hemisphere and also on the high mountains of tropical Africa. The common name, shared with the closely related genus Consolida, is Larkspur.

The leaves are deeply lobed with 3-7 toothed, pointed lobes. The main flowering stem is erect, and varies greatly in size between the species, from 10 cm in some alpine species, up to 2 m tall in the larger meadowland species; it is topped by many flowers, varying between purple, blue, red, yellow or white. The flower has five petals which grow together to form a hollow flower with a spur at the end, which gives the plant its name. The seeds are small and shiny black. The plants flower from late spring to late summer, and are pollinated by butterflies and bumble bees. Despite the toxicity, Delphinium species are used as food plants by the larvae of some Lepidoptera species including Dot Moth and Small Angle Shades.

Other names are, lark's heel (Shakespeare), lark's claw and knight's spur. The scientific name is taken from Dioscorides and describes the shape of the bud, which is thought to look like a (rather fat) dolphin.

The Forking Larkspur (Delphinium consolida) prefers chalky loams. It grows wild in cornfields, but has become very rare nowadays. The flowers are commonly purple, but a white variety exists as well.

Baker's larkspur (Delphinium bakeri) and Yellow larkspur (Delphinium luteum), both native to very restricted areas of California, are highly endangered species.

Cultivation and uses

Many species are cultivated as garden plants, with numerous cultivars having been selected for their denser, more prominent flowers. All parts of the plant contain an alkaloid delphinine and are very poisonous, causing vomiting when eaten, and death in larger amounts. In small amounts, extracts of the plant have been used in herbal medicine. Gerard's herbal reports that drinking the seed of larkspur was thought to help against the stings of scorpions, and that other poisonous animals could not move when covered by the herb, but does not believe it himself. Grieve's herbal reports that the seeds can be used against parasites, especially lice and their nits in the hair. A tincture is used against asthma and dropsy. The juice of the flowers, mixed with alum, gives a blue ink.

The plant was connected to Saint Odile and in popular medicine used against eye-diseases. It was one of the herbs used on the feast of St. John and as such warded against lightning. In Transylvania, it was used to keep witches from the stables, probably because of its blue color.

Larkspur, especially tall larkspur, is a significant cause of cattle poisoning on rangelands in the western United States. Larkspur is more common in high-elevation areas, and many ranchers will delay moving cattle onto such ranges until late summer when the toxicity of the plants is reduced.

Growing

History

An illustrated revision of an article

written by David Bassett for "Delphiniums 98"

the YearBook of the Delphinium Society

A quick look at books about delphiniums shows that many begin by referring to the recognition by the ancient Greeks of the dolphin-like appearance of the unopened flower. The next sentence then introduces Delphinium staphisagria and mentions the almost magical properties of its poisonous seeds as herbal medicine or pesticide. To most gardeners, however, this plant remains just part of Greek mythology, rather than a living representative of the flora of Greece. Delphinium staphisagria thus represents a challenge but in 1997 I succeeded in growing it to flower.

Seed of Delphinium staphisagria, which is a biennial plant, is seldom available and my first attempts to grow it some years ago were with seed Shirley obtained via seed exchanges between Botanical Gardens and Universities. This time we bought seed listed by the Archibalds, which had been collected from plants growing among open scrub at 750 m at Anapoli, Crete. The plant name refers to the resemblance of the leaves to a grape or 'wild raisin' but you could be forgiven for thinking it was the large seeds that looked like raisins. They should certainly not be kept in the cupboard with your dried fruit! The average size for the long axis of 32 seeds was 6.2 mm and the average width across the seeds was 5.2 mm. The seeds are angular with flat facets and a rough, ridged dark brown skin.

The first step is to germinate the seeds, so we tried several methods. I chitted 10 seeds on wet paper towel in a box on a propagator at 22ºC. Shirley put her 10 seeds on wet paper towel in a box that went into the fridge for a cold, wet soak before keeping them at room temperature. In view of the hard skins, I chipped 5 seeds as is often done for seeds of sweet peas . After 16 days, there was great joy because one chipped seed had put out a root. That was in February, but it was to be the only germination until after I abandoned chitting and sowed the remaining 9 seeds in the garden in early May. Four weeks later, after some warm weather and occasional rain, three more seedlings germinated and grew to plants that flowered in September.

Obviously, we are unable to provide a more reliable recipe for germination of this species than committing the seeds to the care of mother nature.

The first germinated seed was sown in a small pot of compost and quickly grew to 'world record' size for a delphinium seedling, measuring 7cm (2.75in) across the cotyledons. Growth from then on was uneventful, producing a rather lush plant with a hairy stem, fairly similar to the closely related biennial species Delphinium requienii but without the glossy surface to the leaves. Unlike Delphinium requienii, the foliage has no offensive odour, even if crushed. The flower spike emerged by early July and the flowers opened after another two weeks.

The bloom is a very loosely-packed, tapered raceme with quite small individual florets (40 mm diam.) held on stiff pedicels (90 mm long at base of bloom) with a bract and a pair of bracteoles right at the base. The bloom was 50 cm long with 27 florets and the blooms of the later plants were of similar size, giving plants with a total height of 1.2 m (4 ft). A notable feature of the floret is that the spur is little more than a knob on the back and is far shorter than for the smaller flowers of Delphinium requieni.

Flower development is interesting in that sepals are greenish yellow on opening. Colour then develops quite slowly, starting from a deep inky-blue edging, moving inwards along the veins and spreading out until the sepals are completely blue.

The petals forming the eye also become coloured and the prominent anthers are purplish brown. The flowers of the plants that grew outdoors in strong sunshine became quite purple, so it is easy to see how one can be confused by descriptions of the colour of this species given in Flora.

The flowers produced plentiful supplies of pollen, so I tried cross-pollinating with Delphinium requienii, using emasculated florets of the latter as the seed parent. These set seed, so the next step will be to find out what sort of plants they produce. (Not done due to house move) The flowers of Delphinium staphisagria also set seed quite readily but, at that stage, the first plant suddenly developed a nasty fungal infection at the base of the stem. It seemed likely to die before the seed could mature so, in desperation, I cut off the bloom and kept it in water containing Chrysal cut flower food for the next two months. This worked and seeds developed even on some of the laterals. Ripening of the seeds seems to be very slow under UK conditions and those set on the plants in the ground were too late to ripen at all. It is interesting that even under bad conditions, seeds have their characteristically large size. The thick-skinned inflated seed pods contain just two or three seeds.

The seed yield from this species is consequently much smaller than from Delphinium requienii, which produces 35+ smaller seeds per floret. The plants die once the seed has ripened.

I ended with four times more seeds than I started with. At this rate of multiplication I would never have sufficient seed to offer Delphinium staphisagria in the seed list of the Delphinium Society. I have no regrets about this, as my impression is that it has less to offer as a plant for garden decoration than Delphinium requienii.

I am now satisfied that I have seen the full life cycle of this fascinating plant. However, it must produce more seed in the wild, or the ancient Greeks would not have had enough to make insecticide powder. To check this, I would of course need a trip to the Greek holiday islands to obtain personal experience of the environment where it grows!

Notes on the availability of seed of Delphinium staphisagria

Seed said to be of this species is sometimes offered by Commercial seed suppliers and Specialist Societies. This winter, 2000/2001, we ordered seeds from The Hardy Plant Society and Chiltern Seeds. In both cases the seed is too small to be Delphinium staphisagria. We have checked with Prof. Cèsar Blanché, an authority on delphiniums of the Mediterranean area, that seed size is indeed a clear distinguishing feature between this species and the rather similar Delphinium requienii.

In our experience, seed of Delphinium requienii is smaller and of a recognizably different shape. Plants of this species are extremely prolific seed producers and the seed germinates very easily.

www.david.bassett.care4free.net

La staphisaigre (Delphinium staphisagria) est une plante herbacée annuelle ou bisannuelle de la famille des Renonculacées. Autres noms communs: Dauphinelle staphisaigre, herbe aux poux, herbe aux goutteux, raisin sauvage.

Description

Les feuilles palmatilobées et profondément découpées sont velues sur les deux faces. La hampe florale, recouverte de poils étalés, mesure de 30 à 100 cm de hauteur et porte de nombreuses fleurs bleu foncé. Le périanthe de la fleur est constitué de cinq sépales pétaloïdes, dont le supérieur se termine par un court éperon. La floraison a lieu de mai à juin.

Habitat

La staphisaigre pousse dans les pelouses arides de la région méditerranéenne. En France, c'est une espèce menacée et protégée.

Aire de répartition

La staphisaigre se retrouve tout autour du bassin méditerranéen, ainsi qu'au Portugal et dans les îles Canaries.

Utilisation

Comme beaucoup d'autres dauphinelles, la staphisaigre est très toxique et contient plusieurs alcaloïdes diterpéniques tels que la delphinine et la chasmanine. Ses graines ont des propriétés insecticides et parasiticides. Elles servent à préparer des pommades ou des décoctions contre les poux et autres parasites externes. La plante est également employée en médecine homéopathique.