Lessico

Razi

Rhazes Rasis Rahzes

Abu Bakr

Muhammad ibn Zakaryya al-Razi

Medico musulmano

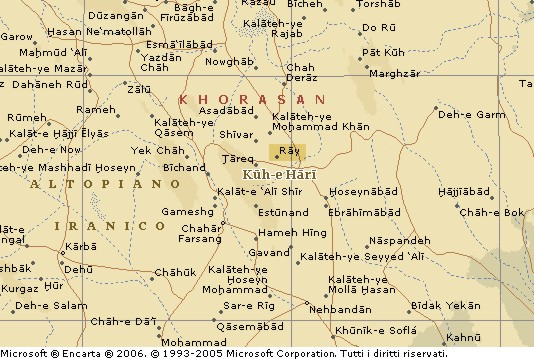

(Ray, Khorasan![]() ,

Persia, ca. 860 - Ray

o Baghdad 925 o 932). I suoi interessi spaziarono dalla filosofia, alla

matematica, all'alchimia, ma fu soprattutto noto come medico pratico.

,

Persia, ca. 860 - Ray

o Baghdad 925 o 932). I suoi interessi spaziarono dalla filosofia, alla

matematica, all'alchimia, ma fu soprattutto noto come medico pratico.

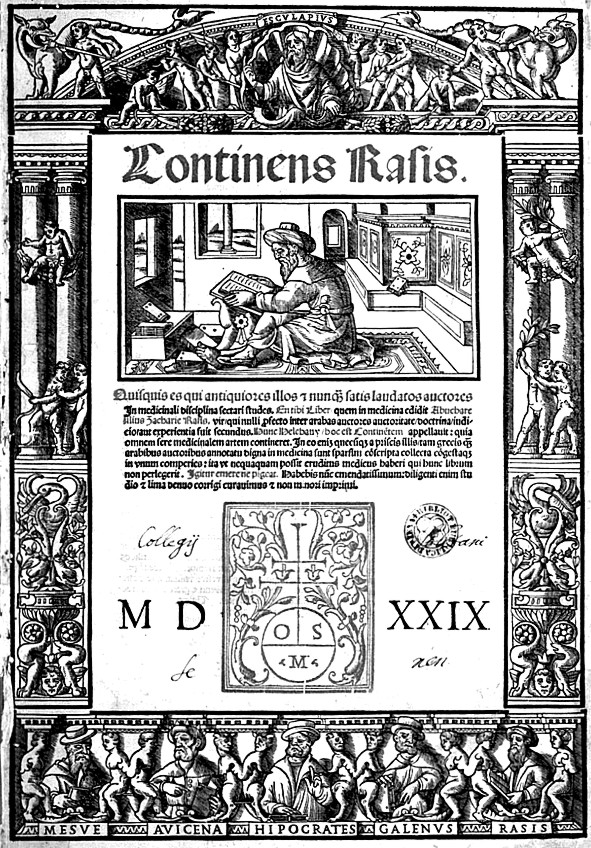

Dei duecento e più libri che scrisse sono ricordati particolarmente al-Hawi (tradotto in latino nel 1486 con il titolo Continens), un compendio con molte interpolazioni nel quale sono raccolte tutte le principali conoscenze mediche e chirurgiche nel mondo islamico e greco, e il Liber medicinalis Almansoris, dedicato al sultano del Khorasan al-Mansur, il Vittorioso. Il nono libro di questo trattato, dedicato alla cura di tutte le malattie, fu assai noto e commentato nelle università italiane dove era conosciuto come Nonus Almansoris.

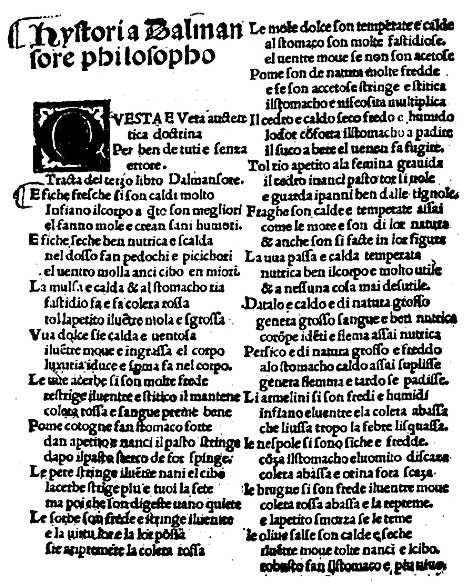

Il

terzo libro dell'Almansor, che contiene una miriade di consigli

dietetici, venne tradotto in italiano nell'ultimo quarto del XV secolo da

un medico veneziano, un certo Arcibaldo o Prencibaldo, detto anche

Cibaldo. Questa traduzione, redatta in versi, prese il nome di Cibaldone

- grande Cibaldo - e diede origine al vocabolo zibaldone![]() .

È assai verosimile che i Veneti, così come gli attuali Tedeschi,

pronunciassero la C come se fosse una Z dolce, o una S, come fanno Spagnoli e

Portoghesi.

.

È assai verosimile che i Veneti, così come gli attuali Tedeschi,

pronunciassero la C come se fosse una Z dolce, o una S, come fanno Spagnoli e

Portoghesi.

Di Razi è importante anche un libro sulle pestilenze dove si trova un'interessante se non la prima descrizione del vaiolo e del morbillo. In alchimia, nell'ambito di una concezione più scientifica della ricerca, la sua opera comprende un buon numero di studi farmacologici inseriti in opere mediche, oltre a una serie di scritti dedicati esclusivamente alla problematica alchimistica tra cui assai noto è il Libro del segreto dei segreti.

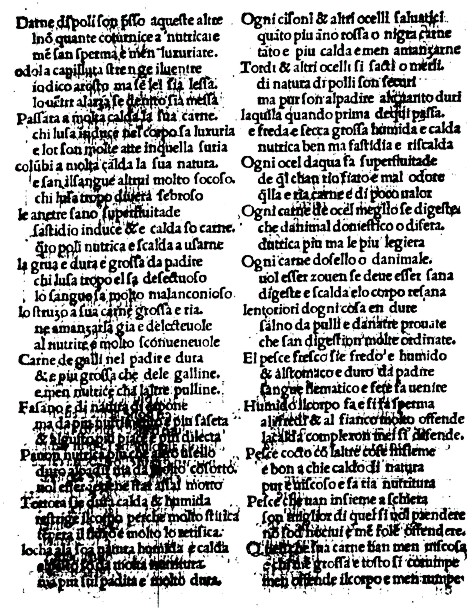

Il Continens edito a Venezia nel 1529

presso Ottaviano Scoto (Monza ca. 1440 - Venezia 1498)

In passato con zibaldone si intendeva una vivanda preparata con gli ingredienti più disparati. Per estensione: mescolanza, confusione di cose o persone diverse. Oggi per zibaldone si intende un quaderno, un libro in cui si annotano disordinatamente ricordi, riflessioni e pensieri. In senso spregiativo: scritto, discorso, brano musicale contenente un insieme disordinato e incoerente di pensieri o immagini di varia natura.

Famoso è lo Zibaldone di Giacomo Leopardi (Recanati 1798 - Napoli 1837), titolo sotto il quale è stato raccolto tutto il complesso di appunti, note, concise osservazioni riguardanti i più diversi temi che Leopardi scrisse senza un ordine prestabilito dal 1817 al 1832 a intervalli discontinui. Rimasto ignorato per molto tempo, lo Zibaldone fu pubblicato da una commissione presieduta da Giosuè Carducci (Valdicastello 1835 - Bologna 1907) in occasione del centenario della nascita del poeta, col titolo di Pensieri di varia filosofia e di bella letteratura (1898-1900) e ristampato nel 1937-38 a cura di Francesco Flora, che preferì il titolo originale leopardiano. Letteratura, filologia, linguistica, arte, filosofia, sociologia, storia, politica costituiscono i temi fondamentali di questo che si può definire una sorta di ricchissimo diario intellettuale, in cui possono ritrovarsi temi e motivi dei Canti e soprattutto delle Operette morali.

Cibaldone - Libro terzo d'Almansore

Bazalerius de Bazaleriis – Bologna, ca. 1493

All'inizio

della seconda colonna della pagina che segue compaiono i cisoni. Altro non

sono che i cigni. Come ci informa Conrad Gessner a pagina 358![]() di Historia animalium III (1555) il cigno era detto cesano dai Veneti.

Aldrovandi a pagina 6 di Ornithologia III (1603) aggiunge che a Ferrara

era detto cisano. Il medico Padovano Antonio Gazio

di Historia animalium III (1555) il cigno era detto cesano dai Veneti.

Aldrovandi a pagina 6 di Ornithologia III (1603) aggiunge che a Ferrara

era detto cisano. Il medico Padovano Antonio Gazio![]() nel suo Florida corona citando il III libro dell'Almansore di

Razi scrive Caro sisonis et aliarum avium silvestrium, frase

correttamente citata da Gessner quando parla dell'impiego del cigno in cucina.

Appare ovvio che la caro sisonis di Gazio è la carne del cisone di

Cibaldone, o carne del cesano, o carne del cisano, o carne del cigno.

nel suo Florida corona citando il III libro dell'Almansore di

Razi scrive Caro sisonis et aliarum avium silvestrium, frase

correttamente citata da Gessner quando parla dell'impiego del cigno in cucina.

Appare ovvio che la caro sisonis di Gazio è la carne del cisone di

Cibaldone, o carne del cesano, o carne del cisano, o carne del cigno.

Frammento dal Florida corona di Antonio Gazio - 1514

“Sull'etimo della parola italiana Zibaldone sono stati emessi vari pareri discordanti, senza che nessuno che se ne sia occupato ne abbia proposto un'etimologia di cui fosse rimasto certo e soddisfatto lui stesso”. Così inizia il suo saggio su L'etimologia della parola italiana zibaldone T. W. Elwert (negli Studi di letteratura veneziana, Venezia-Roma, 1958, pp. 63-70, ristampa di un articolo apparso in Paideia X, 1955, 303-307), il quale ritiene che il primo significato sia stato quello di “miscellanea di scritti, memorie, appunti” e che zibaldone in questo senso risalga a Zibaldone (scritto Cibaldone), “nome di un ignoto medico veneziano che ridusse in versi italiani il terzo libro dell'Almansore del medico arabo Rhazes; questo era un trattato d'igiene e conteneva particolarmente consigli per la scelta dei cibi” (p. 67), tradotto in italiano nell'ultimo quarto del sec. XV. Il nome del medico sarebbe raccorciato da (Ar)cibaldo o (Pren)cibaldo con il suffisso accrescitivo -one (p. 68). Al nome Arcibaldo aveva già pensato l'Ageno Rib. 434 a proposito di un uso di F. Sacchetti, av. 1400: “Lasciai il calamaio e la penna, / che scrisse / insino a questo punto ciò che vi si disse / che non capea nel mio cerbacone, / recando meco cotal zibaldone”. Questa data, che si allinea con lo zibaldonaccio di A. Andreini (sec. XIV, ma forse copia del XVI) e con lo zibaldone del Pataffio (sec. XV), costringe a ritenere noto il volgarizzamento di Rhazes da almeno un secolo. (Dizionario etimologico della lingua italiana di Cortelazzo-Zolli, 1984)

Alquimia![]() entre os Árabes

entre os Árabes

|

A origem da alquimia árabe é dificil de ser estabelecida mas,

certamente, seu cultivo floresceu com o advento do Islã, após a

morte do profeta Maomé, em 632 d.C. Antes deste período, entre 400

d.C. e 700 d.C., há poucas informações disponíveis mas há evidências

de que as idéias gregas de alquimia foram obtidas através do Egito,

da Síria e da Persia. A

cultura islâmica foi o resultado da influência Bizantina, Nestoriana

e Judia, que tinha como componente fundamental as idéias gregas e

helenistas. No

século seguinte à morte do profeta o Islã conquistou a Pérsia, a

Ásia Menor, o Egito, a Palestina, o norte da África e parte da

Europa, Gilbratar e Espanha. Em 732 d.C. a arremetida árabe foi

detida em Poitier, França. Nos

séculos VII e VIII os árabes consolidaram seus domínios e

dedicaram-se a absorver a cultura dos centros de saber conquistados,

principalmente os gregos e os egípcios. Fundaram-se academias e

centros de estudos, nos séculos VIII e IX, tendo os árabes se

empenhado na tarefa de traduzir as obras gregas em filosofia,

astronomia, matemática, medicina , religião, alquimia. Os cristãos

na Síria lideraram este movimento sendo também resposáveis pela

disseminação dos conhecimentos alquímicos dos gregos e egípcios de

Alexandria. Um

livro de alquimia mística com forte vinculação egípcia, o Livro

de Crates (Democritos Em

Harran, uma cidade que era um centro eclético de estudos filosóficos,

havia já muito tempo, com mistura de idéias sírias, persas e gregas,

e onde se cultivava a alquimia, que tinha se tornado muito popular, o

trabalho e o comércio com metais e outras substâncias era intenso. É

natural que as idéias de transmutação de metais e outros conceitos

da alquimia grega e egípcia tivessem sido adotados e enriquecidos

pelos árabes neste período. O

alquimista muçulmano mais famoso é Jabir ibn Hayyan

(721?-803), considerado o pai da alquimia árabe. Após

ter seu pai decapitado, por participar numa tentativa de derrubada do

Califa, foi para a Arabia onde uniu-se a uma seita Xiita chamada

Ismailiia. Esta seita cultivava doutrinas místicas, numerologia Pitagórica

e adotava uma cosmologia que preconizava uma relação entre o

macrocosmo e o microcosmo. Também patrocinava a publicacão de

trabalhos em alquimia. Há mais de 2.000 trabalhos atribuidos a Jabir

num período que se estende até o século XIV. Isto indica que, na

realidade, outros autores da Ismailiia assinavam os manuscritos, para

garantir circulação, com o nome de Jabir, que na Europa ficou

conhecido, séculos depois, como Geber. Por este motivo as obras de Jabir são tambem conhecidas como a Coletânea

de Jabir. A filosofia natural de Jabir estava relacionada com as

doutrinas alquímicas de Alexandria e a filosofia de Aristoteles. Entretanto,

embora adotando o conceito dos quatro elementos- fogo, terra, água e

ar- e suas qualidades- calor, frio, umidade, e secura- achava que duas

delas se combinavam constituindo as qualidades " exteriores"

dos metais enquanto as restantes eram "interiores" e inatas.

Supunha

que metais eram constituidos de mercúrio combinado com enxôfre e que

diferiam uns dos outros pela diferença de suas qualidades. Acreditava

que se a proporção das qualidades fôsse conhecida em determinado

metal, e se estas fossem separadas do mesmo, haveria a possibilidade

de combiná-las em novas proporções e obter metal diferente. Desta

maneira seria possível transformar metais em ouro. Na parte

operacional a distilação destrutiva procurava isolar estas naturezas

primitivas dos elementos alquímicos. As

substâncias eram então destiladas repetidamente, frequentemente

centenas de vezes, na esperança de isolar as qualidades básicas.

Supunha-se também que a adição de uma outra substância, que teria

o poder de absorver uma das qualidades, facilitaria esta tarefa. Um

outro alquimista muçulmano de destaque, que se dedicou à medicina,

é Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakaryya al-Razi (866-925), conhecido como

Rahzes em Latim, nascido na cidade de Ray ou Rhagae. Escreveu 21

livros de alquimia mas sòmente alguns são conhecidos. No Kitab

Sirr al-Asrar (Livro do Segredo dos Segredos) Razi faz

uma exposição minunciosa e classificatória dos equipamentos e das

substâncias utilizadas até então na alquimia. Classificava

as substâncias como animal, vegetal e mineral. As

minerais podiam ser espíritos, pedras, corpos, vitríolos, boraxes e

sais. Os espíritos podiam ser de quatro variedades: dois voláteis e

incombustíveis, o mercúrio e o sal amoníaco, e dois voláteis e

combustíveis, o enxôfre e o ‘arsênico’ (realgar ou orpimento). As pedras incluiam: galena, stibnita, hematita,

pirita, malaquita, vidro, lapis lazuli e gesso. Sua classificação

dos vitriolos não é muito clara mas incluia neles o sulfato ferroso

e o alumen. Os boraxes incluiam o natrão e os sais incluiam o sal

comum, a cal hidratada e os carbonatos de sódio e potássio. No seu

livro Razi menciona outros materiais de uso comum: cinábrio, chumbo

branco e vermelho, litargírio, óxido de ferro, óxido de cobre,

vinagre de vinho. Os equipamentos usados no laboratório incluiam

frascos, caçarolas, cristalizadores de vidro, copos, jarros com tampa,

espátulas, pinças, moinho de pedra para trituração e cadinhos

simples e duplos para a purificação de metais. Fornos

de vários tipos, entre os quais o athanor,

ou al-tannur,

um fôrno feito de tijolos, no fundo do qual se colocava um recipiente

com cinzas envolvendo o material a ser tratado, eram frequentemente

usados. Para aquecimento usavam velas, chamas de nafta, carvão, e

outros materiais combustíveis. As chamas eram sopradas com foles de

couro mas as chaminés não eram ainda utilizadas. Os sistemas de

destilação usados neste período eram praticamente iguais aos dos

alquimistas de Alexandria. O alambique, ou retorta, era mergulhado em

cinzas ou em água sob ação do aquecimento. Razi

também descreve, no seu livro, receitas para a preparação de muitas

substâncias, entre as quais polisulfeto de calcio, a partir de enxôfre

e cal virgem, e álcalis cáusticos a partir de carbonato de sódio (al-Qili)

, cal e sal amoníaco. O al-Qili era obtido por lixiviação de cinzas

de plantas. A solução resultante podia dissolver vários materiais

incluindo a mica. Os textos de Jabir e al-Razi inclinam-se mais para

uma apresentação da alquimia prática, experimental, deixando de

lado a parte mística e filosófica típica de Alexandria. Assim,

embora admitissem a transmutação de metais e a busca de elixires, os

principais alquimistas desta época concentraram-se mais nos aspectos

práticos da arte no laboratório. Esta atitude influenciou não

só os alquimistas muçulmanos posteriores como também, séculos mais

tarde, os alquimistas europeus. Um

grande filósofo-cientista surgiu na Pérsia no século X, Abu ‘Ali

al-Husayn ibn ´Abd Allah ibn Sina (980-1037) ou Avicena, seu nome no

ocidente. Avicena, um insaciável estudioso, dedicou-se à medicina e

à filosofia tendo sido considerado, pelo seu vasto conhecimento, o

principal sábio da Pérsia. É reconhecido no ocidente como príncipe

da medicina. Não era filiado à seita Ismailiia tendo

desenvolvido seus conhecimentos por conta propria. Possivelmente esta

ocurrência tenha-lhe proporcionado uma visão mais racionalista da ciência.

Escritor prolífico deixou mais de

200 tratados sôbre quase todos os assumtos de seu tempo. Era

um médico extraordinário e um experimentador lúcido. Embora

aceitasse a teoria aristotélica dos elementos Avicena rejeitava a

transmutação de metais. Reconhecia que o que os alquimistas

conseguiam na verdade era fazer imitações colorindo os metais

vulgares de branco (prata), amarelo (ouro) e côr de cobre. Acreditava

que estas qualidades eram impingidas aos metais e que os processos

usados, entre os quais a fusão, por exemplo, não podiam afetar a

proporção de seus elementos constituintes. Considerava

que a proporção de tais elementos era uma característica de cada

metal. Assim como suas obras as idéias alquímicas de Avicena tiveram

grande influência nos séculos posteriores. No

final do século X aparece um outro livro famoso, Rutbat al-Hakim

ou Avanço do Sábio, de autoria de Maslama al-Majriti. Era

um famoso astrônomo mourísco da Espanha, país que tinha sido

subjugado pelos árabes no século VIII. Este livro expõe

essencialmente as mesmas idéias dos alquimistas muçulmanos, como

Jabir, mas aborda detalhes experimentais que indicavam uma preocupação

com aspectos quantitativos das transformações observadas. A alquimia

no mundo muçulmano atingiu seu apogeu no século X. Como reflexo da

situação política inconstante não sofreu avanços racionais na sua

interpretação. Apesar disto os árabes contribuiram substancialmente

para a formulação da teoria da composição das substâncias (teoria

enxôfre-mercúrio). Cultivaram com intensidade os paradigmas da

alquimia helenista já conhecidos de séculos anteriores. A parte mística

da alquimia intensificou-se, entretanto, embora nos séculos XI,XII e

XIII surgissem comentaristas e divulgadores da arte, que não

acrescentaram nada de importante. Um dos grandes méritos dos

alquimistas árabes foi a tradução das principais obras dos autores

antigos para a sua língua e o enriquecimento das idéias de forma

mais objetiva. A divulgação destas obras pelo seu império permitiu, mais tarde, uma verdaderira revolução cultural na Europa. Do ponto de vista da alquimia experimental aperfeiçoaram a prática da destilação orientando-a para a separação dos princípios básicos constituintes das substâncias. Progrediram na classificação dos minerais e contribuiram para a descoberta dos álcalis. Fizeram progressos no uso de elixires na medicina e na transformação de metais além do estudo de substâncias orgânicas. da http://143.107.237.20 |

Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (Persian: Zakaria ye Razi; Latin: Rhazes or Rasis) was a Persian alchemist, chemist, physician, philosopher and scholar. According to al-Biruni, al-Razi was born in Rayy, Iran, in the year 865 AD (251 AH), and died there in 925 AD (313 AH).

Razi made fundamental and enduring contributions to the fields of medicine, alchemy, and philosophy, recorded in over 184 books and articles in various fields of science. He was well-versed in Persian, Greek and Indian medical knowledge and added substantially to them from his own observations and discoveries.

Influence

As an alchemist, Razi is known for his study of sulfuric acid, which is often called the "work horse" of modern chemistry and chemical engineering. He also discovered ethanol and refined its use in medicine.

Razi was a rationalist, and was very confident in the power of reason; he was widely regarded by his contemporaries and biographers as liberal and free from any kind of prejudice, very bold and daring in expressing his ideas without a qualm.

He traveled extensively and rendered service to several princes and rulers, especially in Baghdad, where his laboratory was located. As a teacher in medicine, he attracted students of all disciplines and was said to be compassionate and devoted to the service of his patients, whether rich or poor.

The modern-day Razi Institute in Tehran, and Razi University in Kermanshah were named after him, and 'Razi Day' ('Pharmacy Day') is commemorated in Iran every August 27.

Biography

In Persian, Razi means "from the city of Rayy (also spelled Ray, Rey, or Rai, old Persian Ragha, Latin Rhagae - formerly one of the great cities of the World)", an ancient town on the southern slopes of the Elburz Range that skirts the south of the Caspian Sea, situated near Tehran, Iran. In this city (like Avicenna) he accomplished most of his work.

In his early life he could have been a jeweller (Baihaqi), a money-changer but more likely a lute-player who changed his interest in music to alchemy. At the age of thirty (Safadi says after forty) he stopped his study of alchemy because its experiments caused an eye-disease, obliging him to search for physicians and medicine to cure it. al-Biruni, Beyhaqi and others, say this was the reason why he began his medical studies. He was very studious working night and day. His teacher was Ali ibn Rabban al-Tabari, a physician and philosopher born in Merv about 192 (808 C.E.) (d. approx. 240 (855 C.E.)). Al-Razi studied medicine and probably also philosophy with ibn Rabban al-Tabari. Therefore his interest in spiritual philosophy can be traced to this master, whose father was a Rabbinist versed in the Scriptures. According to Prof. Hamed Abdel-reheem Ead, Professor of Chemistry at the Faculty of Science, University of Cairo: " (...) Al-Razi took up the study of medicine after his first visit to Baghdad, when he was at least 30 years old, under the well-known physician Ali ibn Sahl (a Jewish convert to Islam, belonging to the famous medical school of Tabaristan or Hyrcania). He showed such a skill in the subject that he quickly surpassed his master, and wrote no fewer than a hundred medical books. He also composed 33 treatises on natural science (not including alchemy), mathematics and astronomy (...)."

Al-Razi became famous in his native city as a physician. He became Director of the hospital of Rayy, during the reign of Mansur ibn Ishaq ibn Ahmad ibn Asad who was Governor of Rayy from 290-296 (902-908 C.E.) on behalf of his cousin Ahmad ibn Isma'il ibn Ahmad, second Samanian ruler. Razi dedicated his al-Tibb al-'Mansuri to Mansur ibn Ishaq ibn Ahmad, which was verified in a handwritten manuscript of his book. This was refuted by ibn al-Nadim', but al-Qifti and ibn abi Usaibi'ah confirmed that the named Mansur was indeed Mansur ibn Isma'il who died in 365 (975 C.E.). al-Razi moved from Rayy to Baghdad during Caliph Muktafi's reign (approx. 289-295 (901-907 C.E.)) where he again held a position as Chief Director of a hospital.

After al-Muktafi's death in 295 (907 C.E.) al-Razi allegedly returned to Rayy where he gathered many students around him. As Ibn al-Nadim relates in Fihrist, al-Razi was then a Shaikh (title given to one entitled to teach) "with a big head similar to a sack", surrounded by several circles of students. When someone arrived with a scientific question, this question was passed on to students of the 'first circle'. if they did not know the answer, it was passed on to those of the 'second circle'... and so on and on, until at last, when all others had failed to supply an answer, it came to al-Razi himself. We know of at least one of these students who became a physician. Al-Razi was a very generous man, with a humane behavior towards his patients, and acting charitable to the poor. He used to give them full treatment without charging any fee, nor demanding any other payment. When he was not occupied with pupils or patients he was always writing and studying.

Some say the cause of his blindness was that he used to eat too many broad beans (baqilah). His eye affliction started with cataracts and ended in total blindness. The rumor goes that he refused to be treated for cataract, declaring that he "had seen so much of the world that he was tired of it." However, this seems to be an anecdote more than a historical fact. One of his pupils from Tabaristan came to look after him, but, according to al-Biruni, he refused to be treated proclaiming it was useless as his hour of death was approaching. Some days later he died in Rayy, on the 5th of Sha'ban 313 (27th of October, 925 C.E.).

Razi's masters and opponents

Razi studied medicine under Ali ibn Rabban al-Tabari, however, Ibn al-Nadim indicates that he studied philosophy under al-Balkhi, who had travelled much and possessed great knowledge of philosophy and ancient sciences. Some even say that al-Razi attributed some of al-Balkhi's books on philosophy to himself. We know nothing about this man called al-Balkhi, not even his full name.

Razi's opponents, on the contrary, are well-known. They are the following:

1. Abu al-Qasim al-Balki, chief of the Mu'tazilah of Baghdad (d. 319 AH/931 CE), a contemporary of al-Razi who wrote many refutations about al-Razi's books, especially in his Ilm al-Ilahi. His disagreements with al-Razi entailed his thoughts on the concept of 'Time'.

2. Shuhaid ibn al-Husain al-Balkhi, with whom al-Razi had many controversies; one of these was on the concept of 'Pleasure', expounded in his Tafdll Ladhdhat al-Nafs which abu Sulaiman al-Mantiqi al-Sijistani quotes in his work Siwan al-Hikmah. Al-Balkhi died prior to 329/940.

3. Abu Hatim al-Razi (Ahmad ibn Hamdan) became the most important of all his opponents (d. 322 AH/933-934 CE) and was one of the greatest Isma'ili missionaries. He published his controversies with al-Razi in his book A'lam al-Nubuwwah. Because of this book, al-Razi's thoughts on Prophets and Religion are preserved for us.

4. Ibn al-Tammar (seemingly being abu Bakr Husain

al-Tammar, says Kraus) was a physician and he too had some disputes with

al-Razi, which is documented by abu Hatim al-Razi in A'lam al-Nubuwwah. Ibn

al-Tammar disagreed with al-Razi's book al-Tibb al-Ruhani but al-Razi

counteracted this. In fact, al-Razi wrote two antitheses:

(a) First refutation of al-Tammar's disagreement with Misma'i concerning 'Matter'.

(b) Second refutation of al-Tammar's opinion of 'the Atmosphere of

subterranean habitations'.

5. Following are authors as described by al-Razi in

his writings:

(a) al-Misma'i, a Mutakallim, who opposed 'materialists', counteracted byan

al-Razi's treatise.

(b) Jarir, a physician who had a theory about 'The eating of black mulberries

after consuming water-melon'.

(c) al-Hasan ibn Mubarik al-Ummi, to whom al-Razi wrote two epistles with

commentaries.

(d) al-Kayyal, a Mutakallim: al-Razi wrote a book on about his Theory of the

Imam.

(e) Mansur ibn Talhah, being the author of the book "Being", which

was criticized by al-Razi.

(f) Muhammad ibn al-Laith al-Rasa'ili whose opposition against alchemists was

disputed by al-Razi.

6. Ahmad ibn al-Tayyib al-Sarakhasi (d. 286 AH/899 CE), was an older contemporary of al-Razi. Al-Razi disagreed with him on the question of 'bitter taste'. He moreover opposed his teacher Ya'qub ibn Ishaq al-Kindi, regarding his writings, in which he discredited alchemists.

More names could be added to this list of all people opposed by al-Razi, specifically the Mu'tazilah and different Mutakallimin.

Contributions to medicine

Smallpox vs. measles

As chief physician of the Baghdad hospital, Razi formulated the first known description of smallpox:

"Smallpox appears when blood 'boils' and is infected, resulting in vapours being expelled. Thus juvenile blood (which looks like wet extracts appearing on the skin) is being transformed into richer blood, having the color of mature wine. At this stage, smallpox shows up essentially as 'bubbles found in wine' - (as blisters) - ... this disease can also occur at other times - (meaning: not only during childhood) -. The best thing to do during this first stage is to keep away from it, otherwise this disease might turn into an epidemic."

This diagnosis is acknowledged by the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1911), which states: "The most trustworthy statements as to the early existence of the disease are found in an account by the 9th-century Persian physician Rhazes, by whom its symptoms were clearly described, its pathology explained by a humoral or fermentation theory, and directions given for its treatment."

Razi's book al-Judari wa al-Hasbah was the first book describing smallpox and measles, and was translated more than a dozen times into Latin and other European languages. Its lack of dogmatism and its Hippocratic reliance on clinical observation shows Razi's medical methods. We quote:

"The eruption of smallpox is preceded by a continued fever, pain in the back, itching in the nose and nightmares during sleep. These are the more acute symptoms of its approach together with a noticeable pain in the back accompanied by fever and an itching felt by the patient all over his body. A swelling of the face appears, which comes and goes, and one notices an overall inflammatory color noticeable as a strong redness on both cheeks and around both eyes. One experiences a heaviness of the whole body and great restlessness, which expresses itself as a lot of stretching and yawning. There is a pain in the throat and chest and one finds it difficult to breath and cough. Additional symptoms are: dryness of breath, thick spittle, hoarseness of the voice, pain and heaviness of the head, restlessness, nausea and anxiety. (Note the difference: restlessness, nausea and anxiety occur more frequently with 'measles' than with smallpox. At the other hand, pain in the back is more apparent with smallpox than with measles). Altogether one experiences heat over the whole body, one has an inflamed colon and one shows an overall shining redness, with a very pronounced redness of the gums."

Razi was the first physician to diagnose smallpox and measles and the first one to distinguish the difference between them.

Allergies and fever

Razi is also known for having discovered "allergic asthma," and was the first physician ever to write articles on allergy and immunology. In the Sense of Smelling he explains the occurrence of 'rhinitis' after smelling a rose during the Spring: Article on the Reason Why Abou Zayd Balkhi Suffers from Rhinitis When Smelling Roses in Spring. In this article he discusses seasonal 'rhinitis', which is the same as allergic asthma or hay fever. Razi was the first to realize that fever is a natural defense mechanism, the body's way of fighting disease.

Pharmacy

Rhazes contributed in many ways to the early practice of pharmacy by compiling texts, in which he introduces the use of 'mercurial ointments' and his development of apparatus such as mortars, flasks, spatulas and phials, which were used in pharmacies until the early twentieth century.

Ethics of medicine

On a professional level, Razi introduced many

practical, progressive, medical and psychological ideas. He attacked

charlatans and fake doctors who roamed the cities and countryside selling

their nostrums and 'cures'. At the same time, he warned that even highly

educated doctors did not have the answers to all medical problems and could

not cure all sicknesses or heal every disease, which was humanly speaking

impossible. To become more useful in their services and truer to their calling,

Razi advised practitioners to keep up with advanced knowledge by continually

studying medical books and exposing themselves to new information. He made a

distinction between curable and incurable diseases. Pertaining to the latter,

he commented that in the case of advanced cases of cancer and leprosy the

physician should not be blamed when he could not cure them. To add a humorous

note, Razi felt great pity for physicians who took care for the well being of

princes, nobility, and women, because they did not obey the doctor's orders to

restrict their diet or get medical treatment, thus making it most difficult

being their physician.

He also wrote the following on medical ethics:

"The doctor's aim is to do good, even to our enemies, so much more to our friends, and my profession forbids us to do harm to our kindred, as it is instituted for the benefit and welfare of the human race, and God imposed on physicians the oath not to compose mortiferous remedies."

Books and articles on medicine

The

Virtuous Life

al-Hawi

This monumental medical encyclopedia in nine volumes — known in Europe also as The Large Comprehensive or Continens Liber — contains considerations and criticism on the Greek philosophers Aristotle and Plato, and expresses innovative views on many subjects. Because of this book alone, many scholars consider Razi the greatest medical doctor of the Middle Ages.

The al-Hawi is not a formal medical encyclopedia, but a posthumous compilation of Razi's working notebooks, which included knowledge gathered from other books as well as original observations on diseases and therapies, based on his own clinical experience. It is significant since it contains a celebrated monograph on smallpox, the earliest one known. It was translated into Latin in 1279 by Faraj ben Salim, a physician of Sicilian-Jewish origin employed by Charles of Anjou, and after which it had a considerable influence in Europe.

The al-Hawi also criticized the views of Galen, after al-Razi had observed many clinical cases which did not follow Galen's descriptions of fevers. For example, he stated that Galen's descriptions of urinary ailments were inaccurate as he had only seen three cases, while al-Razi had studied hundreds of such cases in Muslim hospitals of Baghdad and Rayy.

A

medical advisor for the general public

Man la Yahduruhu Al-Tabib

Razi was possibly the first Persian doctor to deliberately write a home Medical Manual (remedial) directed at the general public. He dedicated it to the poor, the traveler, and the ordinary citizen who could consult it for treatment of common ailments when a doctor was not available. This book, of course, is of special interest to the history of pharmacy since similar books were very popular until the 20th century. Razi described in its 36 chapters, diets and drug components that can be found in either an apothecary, a market place, in well-equipped kitchens, or and in military camps. Thus, every intelligent person could follow its instructions and prepare the proper recipes with good results.

Some of the illnesses treated were headaches, colds, coughing, melancholy and diseases of the eye, ear, and stomach. For example, he prescribed for a feverish headache: "2 parts of duhn (oily extract) of rose, to be mixed with 1 part of vinegar, in which a piece of linen cloth is dipped and compressed on the forehead". He recommended as a laxative, " 7 drams of dried violet flowers with 20 pears, macerated and well mixed, then strained. Add to this filtrate, 20 drams of sugar for a drink. In cases of melancholy, he invariably recommended prescriptions, which included either poppies or its juice (opium), clover dodder (Cuscuta epithymum) or both. For an eye-remedy, he advised myrrh, saffron, and frankincense, 2 drams each, to be mixed with 1 dram of yellow arsenic formed into tablets. Each tablet was to be dissolved in a sufficient quantity of coriander water and used as eye drops.

Doubts

About Galen

Shukuk 'ala alinusor

Rhazes's independent mind is strikingly revealed in this book and G. Stolyarov II quotes:

"In the manner of numerous Greek thinkers, including Socrates and Aristotle, Rhazes rejected the mind-body dichotomy and pioneered the concept of mental health and self-esteem as being essential to a patient's welfare. This "sound mind, healthy body" connection prompted him to frequently communicate with his patients on a friendly level, encouraging them to heed his advice as a path to their recovery and bolstering their fortitude and determination to resist the illness and resulting in a speedy convalescence."

In his book Doubts about Galen, Razi rejects several claims made by the Greek physician, as far as the alleged superiority of the Greek language and many of his cosmological and medical views. He links medicine with philosophy, and states that sound practice demands independent thinking. He reports that Galen's descriptions do not agree with his own clinical observations regarding the run of a fever. And in some cases he finds that his clinical experience exceeds Galen's.

He criticized moreover Galen's theory that the body possessed four separate "humors" (liquid substances), whose balance are the key to health and a natural body-temperature. A sure way to upset such a system was to insert a liquid with a different temperature into the body resulting in an increase or decrease of bodily heat, which resembled the temperature of that particular fluid. Razi noted particularly that a warm drink would heat up the body to a degree much higher than its own natural temperature. Thus the drink would trigger a response from the body, rather than transferring only its own warmth or coldness to it.

This line of criticism essentially had the potentiality to destroy completely Galen's Theory of Humours including Aristotle's theory of the Four Elements, on which it was grounded. Razi's own alchemical experiments suggested other qualities of matter, such as "oiliness" and "sulphurousness", or inflammability and salinity, which were not readily explained by the traditional fire, water, earth, and air division of elements.

Razi's challenge to the current fundaments of medical theory were quite controversial. Many accused him of ignorance and arrogance, even though he repeatedly expressed his praise and gratitude to Galen for his commendable contributions and labors saying:

"I prayed to God to direct and lead me to the truth in writing this book. It grieves me to oppose and criticize the man Galen from whose sea of knowledge I have drawn much. Indeed, he is the Master and I am the disciple. Although this reverence and appreciation will and should not prevent me from doubting, as I did, what is erroneous in his theories. I imagine and feel deeply in my heart that Galen has chosen me to undertake this task, and if he were alive, he would have congratulated me on what I am doing. I say this because Galen's aim was to seek and find the truth and bring light out of darkness. I wish indeed he were alive to read what I have published."

Crystallization of ancient knowledge, and the refusal to accept the fact that new data and ideas indicate that present day knowledge ultimately might surpass that of previous generations.

Razi believed that contemporary scientists and scholars are by far better equipped, more knowledgeable, and more competent than the ancient ones, due to the accumulated knowledge at their disposal. Razi's attempt to overthrow blind acceptance of the unchallenged authority of ancient Sages, encouraged and stimulated research and advances in the arts, technology, and sciences.

Books on medicine

This is a partial list of Razi's books and articles in medicine, according to Ibn Abi Usaybi'ah. Some books may have been copied or printed under different names.

al-Hawi, al-Hawi al-Kabir. Also known as The

Virtuous Life, Continens Liber. The large medical Encyclopedia containing

mostly recipes and Razi's notebooks.

Isbateh Elmeh Pezeshki, An Introduction to Medical Science.

Dar Amadi bar Elmeh Pezeshki

Rade Manaategha 'tibb jahez

Rade Naghzotibbeh Nashi

The Experimentation of Medical Science and its Application

Guidance

Kenash

The Classification of Diseases

Royal Medicine

For One Without a Doctor

The Book of Simple Medicine

The Great Book of Krabadin

The Little Book of Krabadin

The Book of Taj or The Book of the Crown

The Book of Disasters

Food and its Harmfulness

al-Judari wa al-Hasbah, The Book of Smallpox and Measles

Ketab dar Padid Amadaneh Sangrizeh (Stones in the Kidney and Bladder)

Ketabeh Dardeh Roodeha

Ketab dar Dard Paay va Dardeh Peyvandhayyeh Andam

Ketab dar Falej

The Book of Tooth Aches

Dar Hey'ateh Kabed

Dar Hey'ateh Ghalb (About Heart Ache)

About the Nature of Doctors

About the Earwhole

Dar Rag Zadan

Seydeh neh/sidneh

Ketabeh Ibdal

Food For Patients

Soodhayeh Serkangabin or Benefits of Honey and Vinegar Mixture

Darmanhayeh Abneh

The Book of Surgical Instruments

The Book on Oil

Fruits Before and After Lunch

Book on Medical Discussion (with Jarir Tabib)

Book on Medical Discussion II (with Abu Feiz)

About the Menstrual Cycle

Ghi Kardan or vomiting

Snow and Medicine

Snow and Thirst

The Foot

Fatal Diseases

About Poisoning

Hunger

Soil in Medicine

The Thirst of Fish

Sleep Sweating

Warmth in Clothing

Spring and Disease

Misconceptions of a Doctors Capabilities

The Social Role of Doctors

Translations

Razi's notable books and articles on medicine (in

English) include:

Mofid al Khavas, The Book for the Elite.

The Book of Experiences

The Cause of the Death of Most Animals because of Poisonous Winds

The Physicians' Experiments

The Person Who Has No Access to Physicians

The Big Pharmacology

The Small Pharmacology

Gout

Al Shakook ala Jalinoos, The Doubt on Galen

Kidney and Bladder Stones

Ketab tibb ar-Ruhani,The Spiritual Physik of Rhazes.

Alchemy

The Transmutation of Metals

Razi's interest in alchemy and his strong belief in the possibility of transmutation of lesser metals to silver and gold was attested half a century after his death by Ibn an-Nadim's book (The Philosophers Stone - Lapis Philosophorum in Latin). Nadim attributed a series of twelve books to al-Razi, plus an additional seven, including his refutation to al-Kindi's denial of the validity of alchemy. Al-Kindi (801-873 CE) had been appointed by the Abbasid Caliph Ma'mum founder of Baghdad, to 'the House of Wisdom' in that city, he was a philosopher and an opponent of alchemy.

Finally we will mention Razi's two best-known alchemical texts, which largely superseded his earlier ones: al-Asrar ("The Secrets"), and Sirr al-Asrar ("The Secret of Secrets"), which incorporates much of the previous work.

Apparently Razi's contemporaries believed that he had obtained the secret of turning iron and copper into gold. Biographer Khosro Moetazed reports in Mohammad Zakaria Razi that a certain General Simjur confronted Razi in public, and asked whether that was the underlying reason for his willingness to treat patients without a fee. "It appeared to those present that Razi was reluctant to answer; he looked sideways at the general and replied":

"I understand alchemy and I have been working on the characteristic properties of metals for an extended time. However, it still has not turned out to be evident to me, how one can transmute gold from copper. Despite the research from the ancient scientists done over the past centuries, there has been no answer. I very much doubt if it is possible..."

Chemical instruments and substances

Razi developed several chemical instruments that remain in use to this day. He is known to have perfected methods of distillation and extraction, which have led to his discovery of sulfuric acid, by dry distillation of vitriol (al-zajat), and alcohol. These discoveries paved the way for other Islamic alchemists, as did the discovery of various other mineral acids by Jabir Ibn Hayyam (known as Geber in Europe).

Razi dismissed the idea of potions and dispensed with magic, meaning the reliance on symbols as causes. Although Razi does not reject the idea that miracles exist, in the sense of unexplained phenomena in nature, his alchemical stockroom was enriched with products of Persian mining and manufacturing, even with sal ammoniac a Chinese discovery. He relied predominantly on the concept of 'dominant' forms or essences, which is the Neoplatonic conception of causality rather than an intellectual approach or a mechanical one. Razi's alchemy brings forward such empiric qualities as salinity and inflammability -the latter associated to 'oiliness' and 'sulphurousness'. These properties are not readily explained by the traditional composition of the elements such as : fire, water, earth and air, as al-óhazali and others after him were quick to note, influenced by critical thoughts such as Razi had.

Major works on alchemy

al-Razi's achievements are of exceptional importance in the history of chemistry, since in his books we find for the first time a systematic classification of carefully observed and verified facts regarding chemical substances, reactions and apparatus, described in a language almost entirely free from mysticism and ambiguity. Razi's scheme of classification of the substances used in chemistry shows sound research on his part.

The

Secret

Al-Asrar

This book was written in response to a request from Razi's close friend, colleague, and former student, Abu Mohammed b. Yunis of Bukhara, a Muslim mathematician, philosopher, a highly reputable natural scientist.

In his book Sirr al-Asrar, Razi divides the subject of "Matter' into three categories as he did in his previous book al-Asrar.

Knowledge and identification of drug components of plant-, animal- and mineral-origin and the description of the best type of each for utilization in treatment.

Knowledge of equipment and tools of interest to and used by either alchemist or apothecary.

Knowledge of seven alchemical procedures and techniques: sublimation and condensation of mercury, precipitation of sulfur and arsenic calcination of minerals (gold, silver, copper, lead, and iron), salts, glass, talc, shells, and waxing.

This last category contains additionally a description of other methods and applications used in transmutation:

* The added mixture and use of solvent vehicles.

* The amount of heat (fire) used, 'bodies and stones', ('al-ajsad' and 'al-ahjar)

that can or cannot be transmuted into corporal substances such of metals and

Id salts ('al-amlah').

* The use of a liquid mordant which quickly and permanently colors lesser

metals for more lucrative sale and profit.

Similar to the commentary on the 8th century text on amalgams ascribed to Al- Hayan (Jabir), Razi gives methods and procedures of coloring a silver object to imitate gold (gold leafing) and the reverse technique of removing its color back to silver. Gilding and silvering of other metals (alum, calcium salts, iron, copper, and tutty) are also described, as well as how colors will last for years without tarnishing or changing. Behind these procedures one does not find a deceptive motive rather a technical and economic deliberation. This becomes evident from the author's quotation of market prices and the expressed triumph of artisan, craftsman or alchemist declaring the results of their efforts "to make it look exactly like gold!". However, another motive was involved, namely, to manufacture something resembling gold to be sold quickly so to help a good friend who happened to be in need of money fast. Could it be Razi's alchemical technique of silvering and gilding metals which convinced many Muslim biographers that he was first a jeweler before he turned to the study of alchemy?

Of great interest in the text is Razi's classification of minerals into six divisions, showing his discussion a modern chemical connotation:

Four SPIRITS (AL-ARWAH) : mercury, sal ammoniac,

sulfur, and arsenic sulphate (orpiment and realgar).

Seven BODIES (AL-AJSAD) : silver, gold, copper, iron, black lead (plumbago),

zinc (Kharsind), and tin.

Thirteen STONES : (AL-AHJAR) Pyrites marcasite (marqashita), magnesia,

malachite, tutty Zinc oxide (tutiya), talcum, lapis lazuli, gypsum, azurite,

magnesia , haematite (iron oxide), arsenic oxide, mica and asbestos and glass

(then identified as made of sand and alkali of which the transparent crystal

Damascene is considered the best),

Seven VITRIOLS (AL-ZAJAT) : alum (ak-shubub), and white (qalqadzs), black ,

red, and yellow (qulqutar) vitriols (the impure sulfates of iron, copper,

etc.), green (qalqand).

Seven BORATES : tinkar, natron, and impure sodium borate.

Eleven SALTS (AL-AMLAH): including brine, common (table) salt, ashes, naphtha,

live lime, and urine, rock, and sea salts. Then he separately defines and

describes each of these substances and their top choice, best colors and

various adulterations.

Razi gives also a list of apparatus used in alchemy. This consists of 2 classes:

Instruments used for the dissolving and melting of metals such as the Blacksmith's hearth, bellows, crucible, thongs (tongue or ladle), macerator, stirring rod, cutter, grinder (pestle), file, shears, descensory and semi-cylindrical iron mould.

Utensils used to carry out the process of transmutation and various parts of the distilling apparatus: the retort, alembic, shallow iron pan, potters kiln and blowers, large oven, cylindrical stove, glass cups, flasks, phials, beakers, glass funnel, crucible, alundel, heating lamps, mortar, cauldron, hair-cloth, sand- and water-bath, sieve, flat stone mortar and chafing-dish.

Secret

of Secrets

Sirr Al-asrar

This is Razi's most famous book which has gained a lot of recognition in the West. Here he gives systematic attention to basic chemical operations important to the history of pharmacy.

Books on alchemy

Here is a list of Razi's known books on alchemy, mostly in Persian:

Modkhele Taalimi

Elaleh Ma'aaden

Isbaate Sanaa'at

Ketabeh Sang

Ketabe Tadbir

Ketabe Aksir

Ketabe Sharafe Sanaa'at

Ketabe Tartib, Ketabe Rahat, The Simple Book

Ketabe Tadabir

Ketabe Shavahed

Ketabe Azmayeshe Zar va Sim (Experimentation on Gold)

Ketabe Serre Hakimaan

Ketabe Serr (The Book of Secrets)

Ketabe Serre Serr (The Secret of Secrets)

The First Book on Experiments

The Second Book on Experiments

Resaale'ei Be Faan

Arezooyeh Arezookhah

A letter to Vazir Ghasem ben Abidellah

Ketabe Tabvib

Philosophy

On existence

Razi believed that a competent physician must also be a philosopher well versed in the fundamental questions regarding existence:

"He proclaimed the absolutism of Euclidean space and mechanical time as the natural foundation of the world in which men lived, but resolved the dilemma of existent infinities by synthesizing this outlook with the atomic theory of Democritus, which recognized that matter existed in the form of indivisible and fathomable quanta. The continuity of space, however, holds due to the existence of void, or a region lacking matter... This is remarkably close to the systems yielded by the discoveries of such later European scientists as John Dalton and Max Planck, as well as the observational and theoretical works of modern astronomer Halton Arp and Objectivist philosopher Michael Miller. Progress, in the view of all these men, is not to be obstructed by a jumble of haphazard and contradictory relativistic assertions which result in metaphysical hodge-podge instead of a sturdy intellectual base. Even in regard to the task of the philosopher, Rhazes considered it to be progressing beyond the level of one's teachers, expanding the accuracy and scope of one's doctrine, and individually elevating oneself onto a higher intellectual plane." (G. Stolyarov II)

Razi is known to have been a free-thinking Islamic philosopher, since he was well-trained in ancient Greek science and philosophy although his approach to chemistry was rather naturalistic. Moreover, he was well versed in the theory of music, as so many other Islamic scientists of that time.

Metaphysics

His ideas on metaphysics were also based on the works of the ancient Greeks:

"The metaphysical doctrine of al-Razi, insofar as it can be reconstructed, derives from his concept of the five eternal principles. God, for him, does not 'create' the world from nothing but rather arranges a universe out of pre-existing principles. His account of the soul features a mythic origin of the world in which God out of pity fashions a physical playground for the soul in response to its own desires; the soul, once fallen into the new realm God has made for it, requires God's further gift of intellect in order to find its way once more to salvation and freedom. In this scheme, intellect does not appear as a separate principle but is rather a later grace of God to the soul; the soul becomes intelligent, possessed of reason and therefore able to discern the relative value of the other four principles. Whereas the five principles are eternal, intellect as such is apparently not. Such a doctrine of intellect is sharply at odds with that of all of Razi's philosophical contemporaries, who are in general either adherents of some form of Neoplatonism or of Aristotelianism. The remaining three principles, space, matter and time, serve as the non-animate components of the natural world. Space is defined by the relationship between the individual particles of matter, or atoms, and the void that surrounds them. The greater the density of material atoms, the heavier and more solid the resulting object; conversely, the larger the portion of void, the lighter and less solid. Time and matter have both an absolute, unqualified form and a limited form. Thus there is an absolute matter - pure extent - that does not depend in any way on place, just as there is a time, in this sense, that is not defined or limited by motion. The absolute time of al-Razi is, like matter, infinite; it thus transcends the time which Aristotle confined to the measurement of motion. Razi, in the cases of both time and matter, knew well how he differed from Aristotle and also fully accepted and intended the consequences inherent in his anti-Peripatetic positions." (Paul E. Walker)

Excerpt from The Philosophical Approach

"(...) In short, while I am writing the present book, I have written so far around 200 books and articles on different aspects of science, philosophy, theology, and hekmat (wisdom). (...) I never entered the service of any king as a military man or a man of office, and if I ever did have a conversation with a king, it never went beyond my medical responsibility and advice. (...) Those who have seen me know, that I did not into excess with eating, drinking or acting the wrong way. As to my interest in science, people know perfectly well and must have witnessed how I have devoted all my life to science since my youth. My patience and diligence in the pursuit of science has been such that on one special issue specifically I have written 20,000 pages (in small print), moreover I spent fifteen years of my life -night and day- writing the big collection entitled Al Hawi. It was during this time that I lost my eyesight, my hand became paralyzed, with the result that I am now deprived of reading and writing. Nonetheless, I've never given up, but kept on reading and writing with the help of others. I could make concessions with my opponents and admit some shortcomings, but I am most curious what they have to say about my scientific achievement. If they consider my approach incorrect, they could present their views and state their points clearly, so that I may study them, and if I determined their views to be right, I would admit it. However, if I disagreed, I would discuss the matter to prove my standpoint. If this is not the case, and they merely disagree with my approach and way of life, I would appreciate they only use my written knowledge and stop interfering with my behaviour."

"In the "Philosophical Biography", as seen above, he defended his personal and philosophical life style. In this work he laid out a framework based on the idea that there is life after death full of happiness, not suffering. Rather than being self-indulgent, man should pursue knowledge, utilise his intellect and apply justice in his life.

According to Al-Razi: "This is what our merciful Creator wants. The One to whom we pray for reward and whose punishment we fear."

In brief, man should be kind, gentle and just. Al-Razi believed that there is a close relationship between spiritual integrity and physical health. He did not implicate that the soul could avoid distress due to his fear of death. He simply states that this psychological state cannot be avoided completely unless the individual is convinced that, after death, the soul will lead a better life. This requires a thorough study of esoteric doctrines and/or religions. He focuses on the opinion of some people who think that the soul perishes when the body dies. Death is inevitable, therefore one should not pre-occupy the mind with it, because any person who continuously thinks about death will become distressed and think as if he is dying when he continuously ponders on that subject. Therefore, he should forget about it in order to avoid upsetting himself. When contemplating his destiny after death, a benevolent and good man who acts according to the ordinances of the Islamic Shari`ah, has after all nothing to fear because it indicates that he will have comfort and permanent bliss in the Hereafter. The one who doubts the Shari`ah, may contemplate it, and if he diligently does this, he will not deviate from the right path. If he falls short, Allah will excuse him and forgive his sins because it is not demanded of him to do something which he cannot achieve." (Dr. Muhammad Abdul-Hadi Abu Reidah)

Books on philosophy

This is a partial list of Razi's books on philosophy. Some books may have been copied or published under different titles.

The Small Book on Theism

Response to Abu'al'Qasem Braw

The Greater Book on Theism

Modern Philosophy

Dar Roshan Sakhtane Eshtebaah

Dar Enteghaade Mo'tazlian

Delsoozi Bar Motekaleman

Meydaneh Kherad

Khasel

Resaaleyeh Rahnamayeh Fehrest

Ghasideyeh Ilaahi

Dar Alet Afarineshe Darandegan

Shakkook

Naghseh Ketabe Tadbir

Naghsnamehyeh Ferforius

Do name be Hasanebne Moharebe Ghomi

Spiritual Medicine

The Philosophical Approach (Al Syrat al Falsafiah)

The Metaphysics

RAZIS.

Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn-Zakaruya al-Razi, A.D. 865-925, known in Latin as Rhazes,

was born in Ray near Teheran, Persia. He was physician, physicist, alchemist,

and the greatest clinician of Islam and the Middle Ages. His most important

work, an encyclopedia of medicine called Kitab al-tibb al-Mansuri (Al-Mansur's

Book of Health), was dedicated to the sultan of Khorasan, al-Mansur. It

was translated into Latin as Liber medicinalis Almansoris by Gerard of

Cremona![]() in the

late twelfth century. Michael Scot used it in his own work, Physiognomica

(Physiognomy), in the early thirteenth century. Al-Razi also wrote a

famous monograph on smallpox and measles entitled Kitab al-jadari

wal-Lasaba in Arabic or De variolis et morbiliis in Latin,

sometimes called La Peste and De pestilentia (On the

pestilence). It is the oldest description of smallpox. He wrote

commentaries on Aristotle's Categories; On Interpretation, a

treatise on Aristotle's Analytica priora; a short treatise on

metaphysics using commentaries on Aristotle's Physica (Physics);

as well as treatises on gynecology, obstetrics, and ophthalmic surgery.

Between 1360 and 1385 Merton College owned a copy of the Liber medicinalis

Almansoris. Razis, which means in Arabic "the man from Ray,"

is a byname of location used as a proper name; it appears in the Physician's

catalogue of authorities, Gen Prol 432.

in the

late twelfth century. Michael Scot used it in his own work, Physiognomica

(Physiognomy), in the early thirteenth century. Al-Razi also wrote a

famous monograph on smallpox and measles entitled Kitab al-jadari

wal-Lasaba in Arabic or De variolis et morbiliis in Latin,

sometimes called La Peste and De pestilentia (On the

pestilence). It is the oldest description of smallpox. He wrote

commentaries on Aristotle's Categories; On Interpretation, a

treatise on Aristotle's Analytica priora; a short treatise on

metaphysics using commentaries on Aristotle's Physica (Physics);

as well as treatises on gynecology, obstetrics, and ophthalmic surgery.

Between 1360 and 1385 Merton College owned a copy of the Liber medicinalis

Almansoris. Razis, which means in Arabic "the man from Ray,"

is a byname of location used as a proper name; it appears in the Physician's

catalogue of authorities, Gen Prol 432.

From

CHAUCER NAME DICTIONARY

Copyright © 1988, 1996 Jacqueline de Weever

Published by Garland Publishing, Inc., New York and London.

Rasis or Rahzes, born Abu-Bakr Muhammad ibn-Zakariya al-Razi (860–932), Persian physician. He was chief physician at the Baghdad hospital. An observant clinician, he formulated the first known description of smallpox as distinguished from measles in a work known as Liber de pestilentia (tr. A Treatise on Smallpox and Measles, 1848). His works were widely circulated in Arabic, and Greek versions and were published in Latin in the 15th cent. They include a textbook of medicine called Almansor and an encyclopaedia of medicine compiled posthumously from his papers and known as Liber continens.

da Columbia Encyclopedia

Abu Bakr Mohammad Ibn Zakariya al-Razi (864-930 AD) was born at Ray, Iran. Initially, he was interested in music but later on he learnt medicine, mathematics, astronomy, chemistry and philosophy from a student of Hunayn Ibn Ishaq, who was well versed in the ancient Greek, Persian and Indian systems of medicine and other subjects. He also studied under Ali Ibn Rabban. The practical experience gained at the well-known Muqtadari Hospital helped him in his chosen profession of medicine. At an early age he gained eminence as an expert in medicine and alchemy, so that patients and students flocked to him from distant parts of Asia.

He was first placed in-charge of the first Royal Hospital at Ray, from where he soon moved to a similar position in Baghdad where he remained the head of its famous Muqtadari Hospital for a long time. He moved from time to time to various cities, specially between Ray and Baghdad, but finally returned to Ray, where he died around 930 A.D. His name is commemorated in the Razi Institute near Tehran.

Razi was a Hakim, an alchemist and a philosopher. In medicine, his contribution was so significant that it can only be compared to that of Ibn Sina. Some of his works in medicine e.g. Kitab al- Mansoori, Al-Hawi, Kitab al-Mulooki and Kitab al-Judari wa al- Hasabah earned everlasting fame. Kitab al-Mansoori, which was translated into Latin in the 15th century A.D., comprised ten volumes and dealt exhaustively with Greco-Arab medicine. Some of its volumes were published separately in Europe. His al-Judari wal Hasabah was the first treatise on smallpox and chicken-pox, and is largely based on Razi's original contribution: It was translated into various European languages. Through this treatise he became the first to draw clear comparisons between smallpox and chicken-pox. Al-Hawi was the largest medical encyclopaedia composed by then. It contained on each medical subject all important information that was available from Greek and Arab sources, and this was concluded by him by giving his own remarks based on his experience and views. A special feature of his medical system was that he greatly favoured cure through correct and regulated food. This was combined with his emphasis on the influence of psychological factors on health. He also tried proposed remedies first on animals in order to evaluate in their effects and side effects. He was also an expert surgeon and was the first to use opium for anaesthesia.

In addition to being a physician, he compounded medicines and, in his later years, gave himself over to experimental and theoretical sciences. It seems possible that he developed his chemistry independently of Jabir Ibn Haiyan. He has portrayed in great detail several chemical reactions and also given full descriptions of and designs for about twenty instruments used in chemical investigations. His description of chemical knowledge is in plain and plausible language. One of his books called Kitab-al-Asrar deals with the preparation of chemical materials and their utilization. Another one was translated into Latin under the name Liber Experimentorum, He went beyond his predecessors in dividing substances into plants, animals and minerals, thus in a way opening the way for inorganic and organic chemistry. By and large, this classification of the three kingdoms still holds. As a chemist, he was the first to produce sulfuric acid together with some other acids, and he also prepared alcohol by fermenting sweet products.

His contribution as a philosopher is also well known. The basic elements in his philosophical system are the creator, spirit, matter, space and time. He discusses their characteristics in detail and his concepts of space and time as constituting a continuum are outstanding. His philosophica! views were, however, criticised by a number of other Muslim scholars of the era.

He was a prolific author, who has left monumental treatises on numerous subjects. He has more than 200 outstanding scientific contributions to his credit, out of which about half deal with medicine and 21 concern alchemy. He also wrote on physics, mathe- matics, astronomy and optics, but these writings could not be preserved. A number of his books, including Jami-fi-al-Tib, Mansoori, al-Hawi, Kitab al-Jadari wa al-Hasabah, al-Malooki, Maqalah fi al- Hasat fi Kuli wa al-Mathana, Kitab al-Qalb, Kitab al-Mafasil, Kitab-al- 'Ilaj al-Ghoraba, Bar al-Sa'ah, and al-Taqseem wa al-Takhsir, have been published in various European languages. About 40 of his manuscripts are still extant in the museums and libraries of Iran, Paris, Britain, Rampur, and Bankipur. His contribution has greatly influenced the development of science, in general, and medicine, in particular.

http://143.107.237.20

Dictionnaire

historique

de la médecine ancienne et moderne

par Nicolas François Joseph Eloy

Mons – 1778