Lessico

Tasso

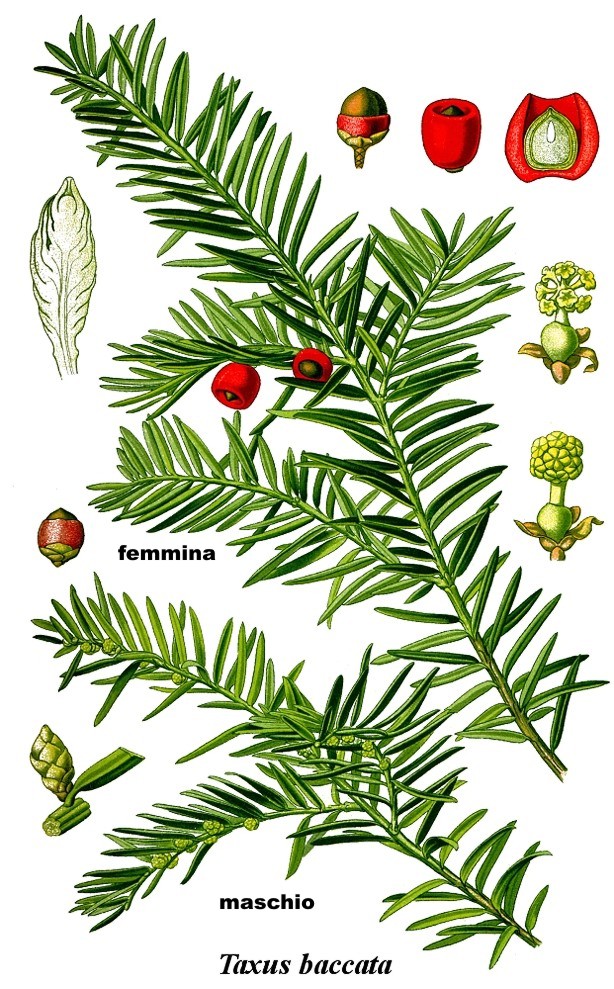

Taxus baccata

Il nome latino del tasso – taxus – pare derivi dal verbo texo, io tesso: infatti le fibre della scorza di tasso erano un tempo utilizzate, come quelle del tiglio, per la confezione di tessuti grossolani.

Taxus baccata: albero della famiglia Taxacee, spontaneo nei terreni calcarei della zona submontana di tutta l'Europa centro-meridionale. È un albero di medie dimensioni, ad accrescimento molto lento, con tronco robusto e corteccia bruna che desquama in lembi sottili. Le foglie sono spesse, lineari, verdi superiormente e biancastre inferiormente, persistenti.

È una

pianta dioica che produce semi avvolti da un arillo![]() carnoso rosso che può essere mangiato, mentre sia i semi nerastri che tutte

le altre parti dell'albero sono velenose, e per questo è anche detto albero

della morte, oltre al fatto che si credeva che dormire sotto le sue fronde

fosse fatale, come vedremo dalla relazione di Plinio

carnoso rosso che può essere mangiato, mentre sia i semi nerastri che tutte

le altre parti dell'albero sono velenose, e per questo è anche detto albero

della morte, oltre al fatto che si credeva che dormire sotto le sue fronde

fosse fatale, come vedremo dalla relazione di Plinio![]() .

.

L’azione letale è fondamentalmente dovuta all’alcaloide tassina isolata dalle foglie per la prima volta da H. Lucas (1856) dotata di azione narcotica e paralizzante sul cuore che si avvicina a quella della veratrina (estratta dalla Sabadilla officinarum o Schoenocaulon officinale).

Sabadilla officinarum o Schoenocaulon officinale

Nell’uomo insorgono disordini digestivi, nervosi, respiratori e cardiovascolari che possono avere come esito la morte. I sintomi consistono in eccitazione, iperventilazione e tachicardia seguita da riduzione della frequenza cardiaca, stordimento, ipotensione arteriosa, vertigini, nausea, dolori gastrici, coliche addominali con diarrea violenta, convulsioni e morte.

Secondo

fonti accreditate le foglie di tasso sono mortali entro un’ora se mangiate

da cavalli, asini e muli, causano gravi intossicazioni in maiali e pecore,

alcuni affermano essere innocue per i bovini (come Teofrasto![]() ,

contestato però da Pierandrea Mattioli

,

contestato però da Pierandrea Mattioli![]() ),

sono innocue per il coniglio, la cavia e il gatto.

),

sono innocue per il coniglio, la cavia e il gatto.

Coltivato a scopo ornamentale, ha una longevità molto elevata, che può arrivare oltre i 1000 anni. Gli uccelli, ghiotti di questi frutti che giungono a maturazione in agosto-settembre, contribuiscono alla disseminazione del tasso attraverso gli escrementi ed è probabile che non muoiano in quanto il loro ventriglio non è in grado di triturare i semi, che sono molto duri.

E mettiamocelo bene in mente: in natura, come pure in vivaio senza ricorrere ad artifizi, la moltiplicazione del tasso si ottiene per seme, all'aperto, nel mese di marzo, alla profondità di 2,5 cm, oppure alla profondità di poco più di mezzo cm in casse, sotto copertura fredda o in serra non riscaldata. Se siamo dei vivaisti possiamo ricorrere a talee - misconosciute in natura - prelevate in settembre dai getti (cioè dai germogli) e messe a radicare in terriccio sabbioso sotto copertura fredda durante l'autunno.

Bisogna inoltre sottolineare che il ventriglio dei polli contiene sì delle pietruzze, ma esse non vengono frantumate, in quanto la loro funzione sarebbe quella di collaborare all’azione di macina esplicata dal ventriglio, che negli uccelli sostituisce i denti. Il ventriglio pone inoltre dei dubbi sulla sua reale funzione digestiva in quanto essendo il pH al suo interno non sufficientemente basso gli enzimi proteolitici non vengono favoriti nella loro attività.

Tronco

de un viejo Tejo

en el Patio de la Acequia de la Alhambra - Granada

Con il tasso si era suicidato Catuvolco, re di una metà degli Eburoni, antico popolo germanico stanziato nella Gallia Belgica, a ovest del

Reno, verso la Mosa, sconfitti nel 54 aC da Giulio Cesare![]() che ne devastò anche il territorio in quanto intendeva sedare definitivamente

le ribellioni di quell'anno. Catuvolco era avanti negli anni, e non essendo in

grado di sopportare le fatiche della guerra o di una fuga, optò per il

suicidio.

che ne devastò anche il territorio in quanto intendeva sedare definitivamente

le ribellioni di quell'anno. Catuvolco era avanti negli anni, e non essendo in

grado di sopportare le fatiche della guerra o di una fuga, optò per il

suicidio.

Ce lo narra lo stesso Giulio Cesare nei Commentarii de bello Gallico VI,31: Catuvolcus, rex dimidiae partis Eburonum, qui una cum Ambiorige consilium inierat, aetate iam confectus, cum laborem aut belli aut fugae ferre non posset, omnibus precibus detestatus Ambiorigem, qui eius consilii auctor fuisset, taxo, cuius magna in Gallia Germaniaque copia est, se exanimavit.

Plinio puntualizza che tra tutte le conifere il tasso è l’unico albero a produrre bacche, particolarmente ricche di veleno in Spagna, e a quei tempi si pensava che fosse il maschio a fruttificare. In Gallia con il legno di tasso si erano costruiti dei recipienti da viaggio per il vino, che si rivelò letale per averne assorbito la tossina. Plinio tramanda anche la leggenda secondo cui il tasso, detto smîlax dai Greci, in Arcadia era dotato di un veleno particolarmente potente, e coloro che dormivano o mangiavano sotto le sue fronde morivano.

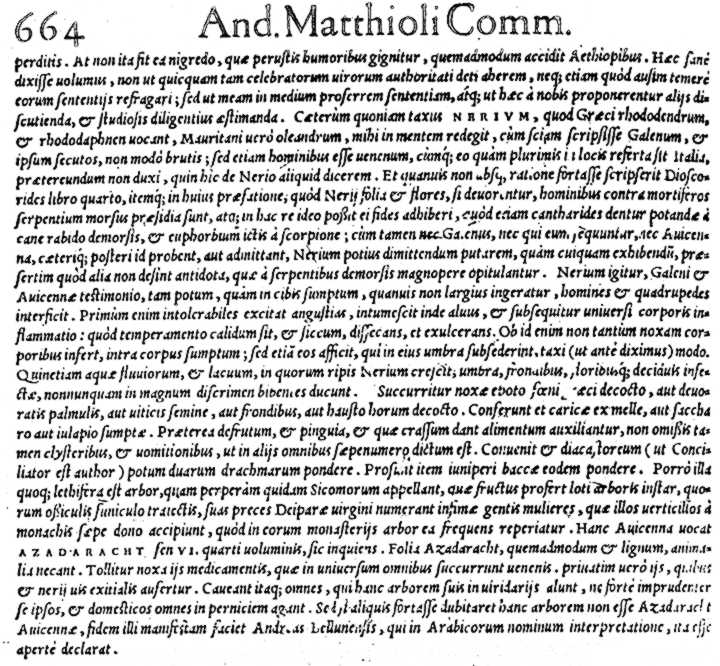

Mattioli

nel suo commento a Dioscoride![]() riporta un’affermazione di Plutarco

riporta un’affermazione di Plutarco![]() che potrebbe forse spiegare perché addormentarsi o fare un picnic sotto a un

tasso sia letale: “come che voglia Plutarco nel terzo Commentario de i suoi

simposii, che non sia velenoso il Tasso, se non quando, essendo egli pregno

d’humore, già comincia a fiorire.”

che potrebbe forse spiegare perché addormentarsi o fare un picnic sotto a un

tasso sia letale: “come che voglia Plutarco nel terzo Commentario de i suoi

simposii, che non sia velenoso il Tasso, se non quando, essendo egli pregno

d’humore, già comincia a fiorire.”

Si può ipotizzare che Plutarco intendesse riferirsi ai granuli di polline che i maschi del tasso lasciano cadere come se fosse una pioggerella, dei quali non sono tuttavia in grado di attestare la velenosità. Ma è più verosimile che Plutarco volesse intendere che quando il tasso fiorisce è in piena attività vegetativa, per cui è più ricco di linfa, e quindi di veleno.

Plinio afferma che pertanto i veleni vennero anche detti taxica, quindi toxica, cioè tossici, ma basta piantare nel tasso un chiodo di bronzo per annullarne gli effetti venefici. Ecco il testo di Plinio Naturalis historia XVI,50-51: Similis his etiamnunc aspectu est, ne quid praetereatur, taxus minime virens gracilisque et tristis ac dira, nullo suco, ex omnibus sola bacifera. Mas noxio fructu; letale quippe bacis in Hispania praecipue venenum inest, vasa etiam viatoria ex ea vinis in Gallia facta mortifera fuisse compertum est. [51] Hanc Sextius smilacem a Graecis vocari dicit et esse in Arcadia tam praesentis veneni, ut qui obdormiant sub ea cibumve capiant moriantur. Sunt qui et taxica hinc appellata dicant venena — quae nunc toxica dicimus —, quibus sagittae tinguantur. Repertum innoxiam fieri, si in ipsam arborem clavus aereus adigatur.

Dal latino medievale arillus, vinacciolo, di origine sconosciuta. Involucro che si sviluppa attorno all'ovulo dei vegetali a partire dal funicolo, di aspetto generalmente carnoso e che permane ad avvolgere il seme, in parte o completamente. Arilli vistosi sono quelli rossi, ricchi di sostanze zuccherine che ricoprono i semi del tasso. Questi arilli, oltre a zuccheri tra cui predomina il raffinosio, al pari delle foglie contengono la letale tassina, ma non danno disordini all’organismo se mangiati in piccole quantità, anzi, servono a preparare sciroppi che, secondo tradizioni popolari, sono efficaci in caso di pertosse, bronchite cronica, idrope, renella.

Il

tasso

è letale per gli uccelli

oppure li fa ingrassare?

Ci renderemo conto una volta di più che non vale la pena accanirsi quando bisogna interpretare i testi antichi da un punto di vista scientifico. Traducendo il testo di Dioscoride relativo al tasso, c'è chi fa morire soffocati gli uccellini che ne mangiano le bacche, altri - come me - asseriscono invece che gli unici uccelli a diventare neri mangiando gli arilli sono i merli quando stanno per diventare dei maschietti maturi, cioè quando cambiano il colore del piumaggio dal tipo femminile caratteristico dei pulcini a quello maschile adulto.

Paradossalmente, grazie agli amanuensi, pare invece che Dioscoride volesse dire che se gli uomini quando si abbuffano di arilli hanno diarrea, invece gli uccellini ingrassano - impinguant, fatten up – e così fanno scorta di energie in previsione della scontata carestia di cibo dovuta all'inverno imminente.

Tutta questa tiritera e la sua soluzione nel senso di uccellini che ingrassano la troverete in inglese, in quanto mi sono spremuto per discuterne con Lily Beck, la quale poi ha mollato tutto ed è svanita nel silenzio assoluto.

March 3rd, 2007

Dear Dr Lily Beck,

I am

disturbing you because I hope that you can help me to solve a problem about

the yew tree of Dioscorides![]() .

.

I have read your very praiseworthy translation of his De materia medica and at page 283 you wrote: "Little birds choke when they eat the fruit of the one growing in Italy and people who eat it come down with diarrhea." (IV,79 σμῖλαξ, Taxus baccata L., Yew)

I have also read the reviews of your translation written by Lynn LiDonnici (2005) and John Riddle (2006) and I gathered that perhaps you have available the translation of Dioscorides done by John Goodyer (between 1652 and 1655).

If yes, I would be interested to know in what way John Goodyer translated the above quoted passage of Dioscorides. This is very important, and later I will clarify the reason, but in summary I can say in advance that until XV-XVI c. they translated the verb μελαίνεται with "to become black", and only recently with something equivalent to "to die". But I think you are quite aware that in usual Greek dictionaries the verb μελαίνω only means to blacken, to become black. I think that if Dioscorides would like to express the death, he would have written ἀποθνῄσκει instead of μελαίνεται.

I am reviewing (and publishing in my site) my English translation of the Latin text about chickens by Ulisse Aldrovandi (Ornithologia vol. II, 1600) and I stopped on a quotation of Dioscorides reported by Aldrovandi.

I quote his Latin text,

where at page 243![]() he says:

he says:

Insigne contra immunitatis privilegium Gallinis (sic enim apud Dioscoridem ὄρνιθες transfero) accessit, cum impune baccis taxi, quae alioqui reliquis animalibus pestiferae sunt, vescantur.

On the contrary an exceptional privilege of immunity happened to hens (for I translate in such way órnithes in Dioscorides) since they safely eat the berries of yew tree, which are otherwise lethal to other animals.

Very often Aldrovandi is

quoting the equivalent text about chickens of Conrad Gessner (Historia

animalium, 1555) without saying his own source. Aldrovandi, as he himself

is affirming, translates órnithes with hens perhaps on Gessner’s suggestion. However, in this passage (book IV

chapter 80 in Jean Ruel![]() ) Dioscorides doesn’t say órnithes but

orníthia, correctly translated into aviculae

by Jean Ruel and meaning little birds, sometimes little pullets, never hens,

whereas when speaking of hens Dioscorides uses alektorìs,

as Aristotle

) Dioscorides doesn’t say órnithes but

orníthia, correctly translated into aviculae

by Jean Ruel and meaning little birds, sometimes little pullets, never hens,

whereas when speaking of hens Dioscorides uses alektorìs,

as Aristotle![]() and Plutarch

and Plutarch![]() do.

do.

Gessner

is giving this short quotation

about the yew tree of Dioscorides in his Historia Animalium III

(1555) pag. 384![]() about rooster and hen:

about rooster and hen:

Taxi fructus edentes in

Italia gallinae nigrescunt, Dioscorides.

The hens in Italy, when eating fruits of yew tree, become black, Dioscorides.

Gessner doesn’t give his reference of this Latin translation of Dioscorides, neither his source. Aldrovandi says: Liber 4, caput 75.

A thing is strange about the abovementioned Gessner’s quotation of Dioscorides. Conrad Gessner, in his Historia plantarum et vires (1541) is choosing the Dioscorides' translation of Jean Ruel, then, orníthia are aviculae, nor I have found any mention of Gallinae nigrescunt and of "death of birds" in the botanical books of Gessner I have available. So, the source of his Taxi fructus edentes in Italia gallinae nigrescunt is unknown. Perhaps this is a personal translation of Gessner which he did for his Historia Animalium III (1555) forgetting the correct Ruel’s translation quoted by him elsewhere.

The Renaissance's

translations of this passage of Dioscorides in my hands are the following,

remembering that Mattioli![]() follows Ruel's

translation.

follows Ruel's

translation.

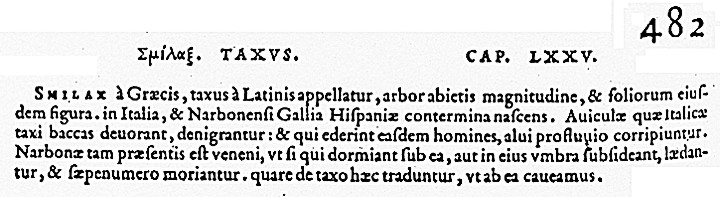

Jean Ruel (1516) – liber IV cap 80 – De Taxo – Smilax a Graecis, taxus a Latinis appellatur, arbor abietis magnitudine, et foliorum eiusdem figura, in Italia et Narbonensi Gallia Hispaniae contermina nascens. Aviculae quae Italicae taxi baccas devorant, denigrantur: et qui ederint easdem homines, alvi profluvio corripiuntur.

Marcellus

Virgilius (alias Marcello Adriani![]() - posthumous, 1523) – liber IV cap. 74 – De

smilace arbore: quae latinis Taxus est – Milaca. Sunt qui Thymion.

Magnitudine foliisque abieti similis et aequalis arbor et in Italia et

Hispaniae Carbonia nascens. Nigrescunt Gallinacei fructu Italicae [taxi]

vescentes. Qui etiam hauserint homines: alvi fluoribus: quos vocant diarrhias

[sic!] vexantur.

- posthumous, 1523) – liber IV cap. 74 – De

smilace arbore: quae latinis Taxus est – Milaca. Sunt qui Thymion.

Magnitudine foliisque abieti similis et aequalis arbor et in Italia et

Hispaniae Carbonia nascens. Nigrescunt Gallinacei fructu Italicae [taxi]

vescentes. Qui etiam hauserint homines: alvi fluoribus: quos vocant diarrhias

[sic!] vexantur.

Pierandrea Mattioli (1554)

– liber IV cap. 75 – Σμῖλαξ Taxus![]() – Smilax a Graecis, taxus a Latinis appellatur,

arbor abietis magnitudine, et foliorum eiusdem figura. in Italia, et

Narbonensi Gallia Hispaniae contermina nascens. Aviculae quae Italicae taxi

baccas devorant, denigrantur: et qui ederint easdem homines, alvi profluvio

corripiuntur.

– Smilax a Graecis, taxus a Latinis appellatur,

arbor abietis magnitudine, et foliorum eiusdem figura. in Italia, et

Narbonensi Gallia Hispaniae contermina nascens. Aviculae quae Italicae taxi

baccas devorant, denigrantur: et qui ederint easdem homines, alvi profluvio

corripiuntur.

Furthermore

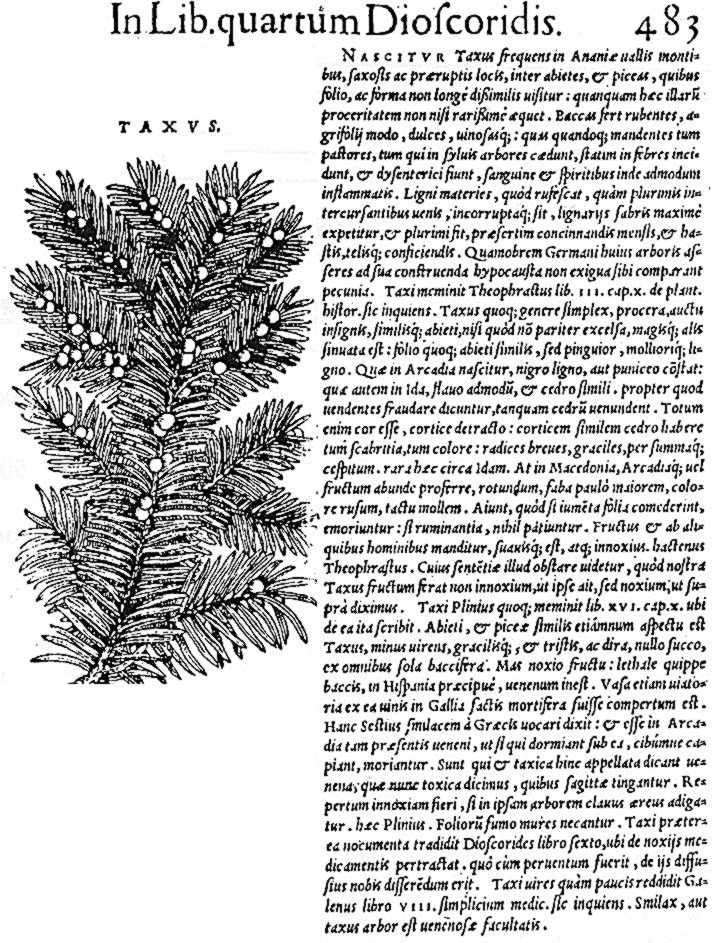

Mattioli (1554) in his commentary of Dioscorides' book VI chapter 12 - Σμῖλαξ Taxus![]() - affirms that the

birds become black because the yew is too much warm:

- affirms that the

birds become black because the yew is too much warm:

Dioscorides quidem, et eius sequaces omnes existimarunt Taxum esse frigidi temperamenti, argumento quod asseruerint, iisdem remediis taxi venenum superari, quibus et cicutae. Quorum tamen sententia, omnium pace dixerim, mihi plane non probanda videtur. Nanque amaror, qui cortici et frondibus inest: coma perpetuo virens, pinorum, abietum, et picearum modo, quibus fronde similis spectatur: baccarum tum dulcedo, tum acrimonia quaedam: et quod aviculae eas depastae nigrescant, manifeste indicant insignem temperamenti caliditatem. Atque hinc est, quod et febribus, et alvi profluvio tentantur, qui baccas esitarunt, inflammatis eo cibo spiritibus, et sanguine.

In a German translation of Dioscorides (by the German Julius Berendes, 1902) which I have found in the web - without Greek text – the orníthia become chicks and the chicks die suffocated when eating yew’s berries:

Wenn die Küken die Frucht des in Italien wachsenden fressen, ersticken sie; [...]

A German friend of mine I asked about the current today's meaning of Küken, replied that they call Küken the chicks of the hens. They call in a different way the chicks of other birds. Then Berendes, with his Küken (chicks of hens) is in opposition with the manner of yew’s seeds dispersion which happens thanks to little birds, which are not dying (perhaps do they die in Italy? but we have yew trees in Italy thanks to them being living!).

Another recent German translation (by Max Aufmesser, 2002) excludes the possibility of thinking about chicks of hen. This translation doesn’t speak of little birds, but of birds in a broad sense, and kills them:

Sie tötet die Vögel, die den Samen der in Italien vorkommenden fressen.

Well,

we have Aldrovandi and Gessner translating orníthia

into gallinae, Marcellus

Virgilius into gallinacei,

Berendes into chicks of hens and

Aufmesser into birds.

Furthermore Aldrovandi says

that hens are surviving when eating berries, while all other animals die,

enclosed any other kind of birds. This affirmation is equivalent to that of

Berendes: no birds are helping in yew’s propagation.

Gessner says that they become black.

Berendes that they suffocate.

Aufmesser that birds are killed.

Truly it is a little bit difficult to imagine why hens, chicks, or better, little birds, become black.

The solution of Berendes is that they become cyanotic – then blackish – because they suffocate. Attention: they suffocate only in Italy. And attention: I think that it is very difficult to check from a certain distance whether a bird is cyanotic. Only chickens have a comb, which can appear cyanotic even if looked from a certain distance. Usually, to know whether a died bird is cyanotic, we have to handle it and check the color of its tongue which perhaps is cyanotic if the bird chocked. But I am not sure of this, I am not a veterinary nor an ornithologist.

Only Mattioli – as quoted above – has done a

long close scrutiny about this Dioscorides’ melaínetai

in the commentary of book VI chapter 12, while Marcellus Virgilius doesn’t

analyze the verb melaínetai. Mattioli thinks that

the black color is taken by bird’s feathers, and this could be true if in

Italy perhaps the black pigments of the seed contained in the berry are so

powerful to give rise to a black plumage in birds after molting like the

canary – Serinus canaria – become reddish in eating paprika ![]()

![]() .

.

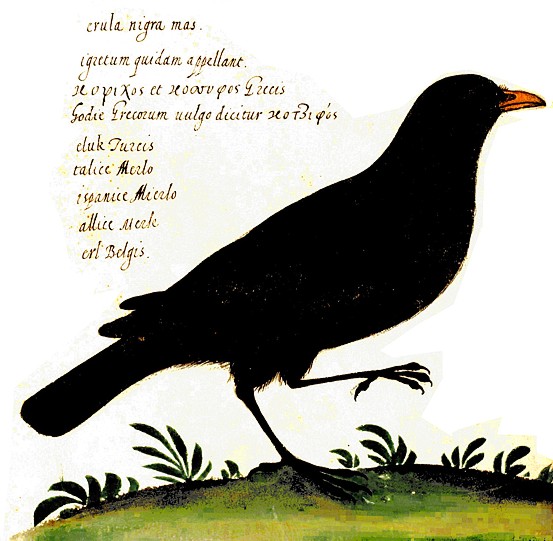

But I think that Dioscorides observed in Italy

some specific birds becoming black when eating yew's fruits, and these birds

could be the blackbirds![]() , Turdus merula.

, Turdus merula.

I don't know whether also today we can observe

what has been observed and painted by the aquarellists![]() of Aldrovandi in XVI century. First of all

the young blackbirds of both sexes are brown and the young males become

gradually black perhaps just when in late summer (August/September) the yew's

fruits are red and ready to be eaten. So the birds assure the dissemination of

the tree.

of Aldrovandi in XVI century. First of all

the young blackbirds of both sexes are brown and the young males become

gradually black perhaps just when in late summer (August/September) the yew's

fruits are red and ready to be eaten. So the birds assure the dissemination of

the tree.

The aquarellists of Aldrovandi have painted in watercolours 3 blackbirds: a male (black), a female (brown) and a third bird which in winter became buff and whose caption sounds: "Merula hyeme ex nigra reddita ruffa". Perhaps the beak of this buff blackbird is that of a female. Be that as it may, a bird formerly black (male) or brown (female) became buff in winter.

I don't know whether in Italy this fact happens also today, or only at times of Aldrovandi, or also at times of Dioscorides. Certainly, this buff bird needs some time in order to become newly black or brown, and perhaps this was happening when the fruits of yew where ready to be eaten: in late summer.

Summarizing

In what way has been translated into English this passage of Dioscorides about orníthia and melaínetai by John Goodyer?

Do you have some English translation of this passage done in XV-XVI century? In order to compare these translation with that of John Goodyer.

I think that the little birds eating yew's fruits don't die, and so they assure the dissemination of this tree. In XVI century Ruel, Mattioli and Marcellus Virgilius (nevertheless his Gallinacei) agree with me.

I don't affirm that the little birds mentioned by Dioscorides are the blackbirds – Turdus merula, but it could be possible, helped by the buff wintry Merula of Aldrovandi portrayed in XVI century.

If you want, I can send you the Aldrovandi's watercolors. This is easier if you have an e-mail

Hoping that this strange query is of interest for you, I am awaiting for your precious suggestions.

Many thanks for your

attention.

And please forgive my English!!!

Sincerely yours,

Elio Corti

From

Lily Beck

March 17th, 2007

Dear Dr. Corti.

Thank you for your letter of March 3, which was forward to me here in Greece. I am leaving Athens tomorrow and will be out of town for the next few weeks before returning to New York via Athens, around the middle of April.

I truly regret not to be able to answer your questions right away but I promise to do so as soon as I am back in the States and, if at all possible, even from Athens.

Sincerely,

Lily Y. Beck

P.S. You can reach me via this email address at any time.

From

Lily Beck

April 30, 2007

Dear Elio,

Thank you so much for the Aldrovandi pictures of Merulas and for waiting patiently for my reply. After spending nearly five months in Greece, I returned to the States a week ago, and as you can well-imagine, I am swamped!

I hope in the following lines to be able to answer all your questions, and if not, please, do not hesitate to contact me.

Let me first say that as far as I know, all taxi are highly poisonous in their entirety, except for their arils, which are not, but which enclose a small, single, highly toxic seed. Taxines are the culprits causing death and producing, in animals, prior to their death, several acute symptoms, e.g., cardiac arrhythmia, ataxia, diarrhea, hypotension, colic, hypothermia, respiratory failure, etc. (Cornell University, Animal Science.)

As you

probably know the taxus was associated with death and was called the "tree

of death". See Ovid![]() , Met.,

IV, 432 (Est via declivis funesta nebula taxo) and Caesar

, Met.,

IV, 432 (Est via declivis funesta nebula taxo) and Caesar![]() , B.

G. 6,31 where Catuvolcus, a king of the Eburones chose death from Taxus

baccata rather than to be taken prisoner.(Catuvolcus, rex dimidiae partis Eburonum, qui una

cum Ambiorige consilium inierat, aetate iam confectus, cum laborem aut belli

aut fugae ferre non posset, omnibus precibus detestatus Ambiorigem, qui eius

consilii auctor fuisset, taxo, cuius magna in Gallia Germaniaque copia est, se

exanimavit.)

, B.

G. 6,31 where Catuvolcus, a king of the Eburones chose death from Taxus

baccata rather than to be taken prisoner.(Catuvolcus, rex dimidiae partis Eburonum, qui una

cum Ambiorige consilium inierat, aetate iam confectus, cum laborem aut belli

aut fugae ferre non posset, omnibus precibus detestatus Ambiorigem, qui eius

consilii auctor fuisset, taxo, cuius magna in Gallia Germaniaque copia est, se

exanimavit.)

I am not aware of any English translation of Materia medica of the XV-XVI c. The first real English translation that I know of prior to mine is that is that of Goodyer between 1652 and 1655 and this translation was not even published until 1934!, when Robert T. Gunther edited it minimally for Hafner of New York. Additionally the Goodyer translation was based on a corrupt Dioscorides edition (Frankfurt1598).

Dioscorides IV,79 σμῖλαξ in the Wellmann text corresponds to IV,80. Please note that Goodyer identifies σμῖλαξ as Quercus Ilex typica, Holm-oak. His translation is as follows:

Smilax, which some call Thymalus, but ye Romans call it Taxus, is a tree like unto ye fir in ye leaves & ye bigness, growing in Italy & Narbonie which is by Spain. But ye chicken which eat ye fruit of that which grows in Italy wax black & ye men that eat it fall into a looseness. But that in Narbonie doth participate of so great force, that they which sit under, or fall asleep, are hurt of the shade, & that often times they die. But this is storied of it, to ye end that it may be taken heed of before.

The "chicken" in Goodyer are the ὀρνύφια in the Wellmann text or ὀρνύθια in its apparatus criticus. I personally believe that these diminutives simply mean "little birds" and I do not know what was the Greek word that Goodyer translates as "chicken" from his Frankfurt edition he used.

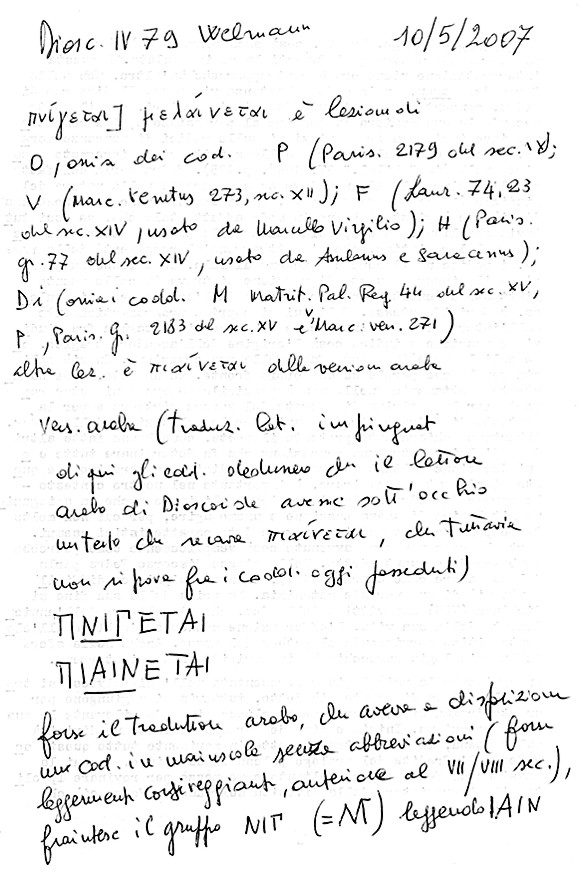

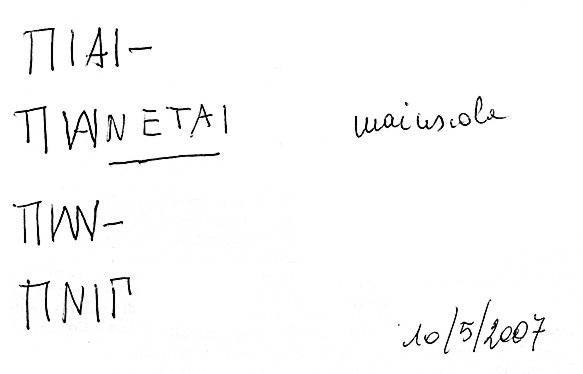

The other difficulty this text presents is with the verb πνίγεται in the established Wellmann text and, according to the app. crit. for the same word, μελαίνεται = grow or become black, and πιαίνεται, inpinguat in Dl.

As you know, I have followed the reading πνίγεται and translated this verb as "die". If one takes into consideration the dictionary definition of πνίγω/πνίγομαι = to choke, strangle, throttle, suffocate, all of which usually result in death because of the compression of the windpipe from stoppage of respiration, if one heeds modern scholarship regarding the toxicity of taxus, if one considers Dioscorides' last sentence in this section: ἱστορεῖται δὲ περὶ αὐτῆς χάριν τοῦ προφυλάσσεσθαι = It [taxus] is mentioned in order to guard against it, and finally, if one observes the location of taxus within the entire corpus of Materia medica, namely, among lethal, sedative, and highly toxic plants, one will have to conclude that the ingestion of taxus causes death rather than that it causes the ingestor to turn black.

Hope I have been helpful. Please, don't hesitate to contact me, if I can be of further assistance.

With best regards,

Lily Beck

May 12th 2007

Dear Lily,

Prof Roberto Ricciardi of Alessandria (who is helping me) transcribed Wellmann's apparatus criticus since his photocopier was unoperating. Furthermore he conjectured a thing which is very interesting. You will receive this material he wrote as JPG files.

As you quoted, in the apparatus criticus there is the Latin verb inpinguat or impinguat.

So, I think that this could be a solution of this discussion, which – I would like to underline – is due to mere biological reasons.

Then we consider the different verbs present in the apparatus criticus:

1 - Μελαίνεται – we have only one possibility (as far as I am aware) in order to accept this verb. This unique possibility is given by young male blackbirds (Turdus merula) which when arils are ready to be eaten are changing their juvenile plumage into black adult plumage. And undoubtedly Turdus merula are ὀρνίθια, that is, little birds. They are not big birds like chickens are (as I still wrote, like Goodyer, also Gessner and Aldrovandi have hens), nor are large like an eagle.

2 - Πνίγεται – If this has been the verb used by Dioscorides, we have to suppose - as you rightly told - a compression of the windpipe from stoppage of respiration. I think that this fact happens very seldom, not only in birds, but also in humans thanks to a reflex triggered by a foreign body. Moreover, from Dioscorides' text we have to infer that ALL little birds die when eating yew's fruits, not only a 10-20-30 % of them and so on.

A little digression: I have chickens. I can assure you that never saw them to die because eating big mouthfuls, nor small mouthfuls which are more dangerous from a respiratory point of view. When I have available not poisoned mice I give them to hens and I am awaiting that they swallow them in order to save the hen from suffocation if the mouse is too much big, grasping the mouse by its tail. Never I had to do this. The hen ever gulped down the mouse.

But a thing is very important from a biological point of view. As already I wrote, if ALL little birds are dying, we have to observe an hecatombe of little birds at the end of summer when arils are ready and moreover – and this is very important – the manner of dissemination of Taxus baccata (a zoophile dissemination) would be very endangered.

3 - Πιαίνεται – This could be the true solution of this discussion. In fact inpinguat could be reliable from a chemical point of view (the arils contain proteins and sugar, the more important being the raffinose = 1 molecule each of glucose, galactose & fructose like in sugar beet). If ALL little birds fatten when eating arils, they prepare themselves for winter when food is scant and are assuring the natural yew's dissemination. You will see how Prof Ricciardi has conjectured the formation of the word πιαίνεται in place of πνίγεται perhaps because of corrupted manuscripts. Among the three readings, at this point, I prefer πιαίνεται.

In this chapter of book IV Dioscorides doesn't speak of death at all as far as fruits is concerned, differently of the very short chapter in book VI. In the former chapter the humans have only diarrhea. Then we can suppose that also ALL little birds mentioned together are not dying when eating arils, like humans are not dying at all.

That's

all. And let me know...

Sincerely yours.

Elio

PS – I send you also the very long lucubration of Mattioli about μελαίνεται in his commentary to yew's chapter of book VI of Dioscorides (pages 663 and 664). In order to be complete, I am also sending his short commentary on yew of book IV (pages 482 and 483). But I am sending these pages only for curiosity. I confess you: I accepted πιαίνεται.

Il tasso (Taxus baccata L.) è un albero dell'ordine delle conifere, molto usato come siepe ornamentale o pianta isolata potata secondo i criteri dell'ars topiaria, cioè del giardino artificiale. Il tasso è un albero sempreverde di seconda grandezza, con una crescita molto lenta. Per questo motivo in natura spesso si presenta sotto forma di piccolo albero o arbusto, tuttavia in condizioni ottimali può raggiungere i 15 – 20 metri di altezza; la chioma ha forma globosa irregolare, con rami molto bassi. La corteccia è di colore bruno rossastro, inizialmente è liscia ma con l'età si solleva arricciandosi e dividendosi in placche. I giovani rami sono verdi. Le foglie sono lineari, leggermente arcuate, lunghe fino a 3 cm e di colore verde molto scuro nella pagina superiore, più chiare inferiormente; sono inserite sui rami con un andamento a spirale, in due file opposte. Sono molto velenose.

È una specie per lo più dioica ma esistono segnalazioni di individui monoici. I fiori maschili sono raggruppati in amenti, quelli femminili si trasformano in arilli. L'impollinazione è anemofila. La pianta, essendo una Pinophyta, non produce frutti (solamente le Angiosperme ne producono). Quelli che sembrano i frutti in realtà sono degli arilli, ovvero delle escrescenze carnose che ricoprono il seme. Inizialmente verdi, rossi a maturità, contengono un solo seme, duro e molto velenoso. La polpa invece è innocua e commestibile, viene mangiata dagli uccelli che ne favoriscono la diffusione per seme. Gli animali mangiano i frutti, che non vengono macinati e digeriti. Quando l'animale li espelle i semi essi sono ancora intatti e si insediano nel terreno dando origine a una nuova pianta. Il tasso è quindi una pianta zoofila, che si serve degli animali per riprodursi. Senza gli animali gli arilli cadrebbero al suolo e non crescerebbero per la mancanza di luce e la concorrenza con la pianta madre per i sali minerali del terreno.

L'areale di diffusione comprende le zone dall'Europa settentrionale al Nordafrica e al Caucaso. Preferisce i luoghi umidi e freschi, ombrosi, con terreno calcareo. In Italia si trova in zone montane, non molto frequentemente. Nella foresta Umbra del Gargano, nella zona di Palena, Pescocostanzo provincia dell'Aquila e nella Riserva naturale guidata Zompo lo Schioppo (AQ) sono presenti diversi esemplari imponenti. Il Parco dei Nebrodi ospita, all'interno del bosco della Tassita, alcuni esemplari maestosi che raggiungono i 25 m di altezza.

Il principio attivo responsabile della tossicità di rami, foglie e semi, dove è presente in percentuale variabile fra lo 0,5 e il 2%, è una molecola estremamente complessa chiamata taxolo. Ha effetto narcotico e paralizzante sull'uomo e su molti animali domestici, a causa dell'inibizione nella sintesi dei microtubuli a livello cellulare. Gli organi che ne contengono di più sono le foglie vecchie. C'è però da dire che molte di queste sostanze tossiche, alle dosi presenti nella pianta, possono essere usate come principi attivi di prodotti chemioterapici per la lotta ad alcune forme di cancro, in particolar modo la tassina è utilizzata in alcune forme neoplastiche a livello ovarico.

È stato molto usato come specie da ars topiaria e tuttora viene spesso impiegato per formare grandi siepi formali, oltre che come esemplare singolo. Sono state selezionate varie cultivar ornamentali, caratterizzate da portamento colonnare, fogliame di colore giallo dorato o caratterizzate da crescita ridotta. Molto longevo, è difficile stabilirne l'età perché gli anelli di crescita del legno non sono sempre visibili a causa di particolari strutture (chiamate cordoni di risalita) che ne impediscono la corretta datazione, inoltre spesso il centro del tronco diventa cavo con il passare del tempo. Nel Giardino dei semplici di Firenze è presente un tasso piantato da Pier Antonio Micheli nel 1720. Ne esistono esemplari di 1500 – 2000 anni di età.

Utilizzo: storicamente il tasso è il legno per eccellenza nella costruzione di archi, e sin dalla preistoria è attestato il suo utilizzo per la fabbricazione di quest'arma. Per esempio, l'arco della mummia del Similaun era in tasso. Ma la fama acquisita dal legno di questa pianta è dovuta soprattutto alla larghissima diffusione che ebbe durante il Medioevo nella costruzione di archi da guerra, soprattutto in Inghilterra (il famoso arco lungo era di tasso). Le caratteristiche che lo rendono così adatto alla fabbricazione di archi sono l'enorme resistenza, sia alla compressione che alla trazione, e l'incredibile elasticità.

An

Irish Yew - Taxus baccata 'Fastigiata'

planted at Kenilworth Castle - Warwik County - UK

Taxus baccata is a conifer native to western, central and southern Europe, northwest Africa, northern Iran and southwest Asia. It is the tree originally known as yew, though with other related trees becoming known, it may be now known as the common yew, or European yew. It is a small- to medium-sized evergreen tree, growing 10–20 metres (33–66 ft) (exceptionally up to 28 m/92 ft) tall, with a trunk up to 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) (exceptionally 4 m/13 ft) diameter. The bark is thin, scaly brown, coming off in small flakes aligned with the stem. The leaves are lanceolate, flat, dark green, 1–4 centimetres (0.39–1.6 in) long and 2–3 millimetres (0.079–0.12 in) broad, arranged spirally on the stem, but with the leaf bases twisted to align the leaves in two flat rows either side of the stem, except on erect leading shoots where the spiral arrangement is more obvious. The leaves are highly poisonous.

The seed cones are highly modified, each cone containing a single seed 4–7 millimetres (0.16–0.28 in) long partly surrounded by a modified scale which develops into a soft, bright red berry-like structure called an aril, 8–15 millimetres (0.31–0.59 in) long and wide and open at the end. The arils are mature 6-9 months after pollination, and with the seed contained are eaten by thrushes, waxwings and other birds, which disperse the hard seeds undamaged in their droppings; maturation of the arils is spread over 2-3 months, increasing the chances of successful seed dispersal. The seed itself is extremely poisonous and bitter. The aril is not poisonous, and is gelatinous and very sweet tasting. The male cones are globose, 3–6 millimetres (0.12–0.24 in) diameter, and shed their pollen in early spring. It is mostly dioecious, but occasional individuals can be variably monoecious, or change sex with time.

It is relatively slow growing, but can be very long-lived, with the maximum recorded trunk diameter of 4 metres probably only being reached in about 2,000 years. The potential age of yews is impossible to determine accurately and is subject to much dispute. There is rarely any wood as old as the entire tree, while the boughs themselves often hollow with age, making ring counts impossible. There are confirmed claims as high as 5,000-9,500 years, but other evidence based on growth rates and archaeological work of surrounding structures suggests the oldest trees (such as the Fortingall Yew in Perthshire, Scotland) are more likely to be in the range of 2,000 years. Even with this lower estimate, Taxus baccata is the longest living plant in Europe.

Most parts of the tree are toxic, except the bright red aril surrounding the seed, enabling ingestion and dispersal by birds. The major toxin is the alkaloid taxane. The foliage remains toxic even when wilted or dried. Horses have the lowest tolerance, with a lethal dose of 200–400 mg/kg body weight, but cattle, pigs, and other livestock are only slightly less vulnerable. Symptoms include staggering gait, muscle tremors, convulsions, collapse, difficulty breathing, and eventually heart failure. However, death occurs so rapidly that many times the symptoms are missed.

In the ancient Celtic world, the yew tree (*eburos) had extraordinary importance; a passage by Caesar narrates that Catuvolcus, chief of the Eburones poisoned himself with yew rather than submit to Rome (Gallic Wars 6: 31). Similarly, Florus notes that when the Cantabrians were under siege by the legate Gaius Furnius in 22 BC, most of them took their lives either by the sword or by fire or by a poison extracted ex arboribus taxeis, that is, from the yew tree (2: 33, 50-51). In a similar way, Orosius notes that when the Gallaecians were besieged at Mons Medullius, they preferred to die by their own swords or by the yew tree poison rather than surrender (6, 21, 1.)

In 1021, Avicenna introduced the medicinal use of Taxus baccata L for phytotherapy in The Canon of Medicine. He named this herbal drug as "Zarnab" and used it as a cardiac remedy. This was the first known use of a calcium channel blocker drug, which were not in wide use in the Western world until the 1960s.

The yew is often found in church yards from England and Ireland to Galicia; some of these trees are exceptionally large (over 3 m diameter) and may be over 2,000 years old. It has been suggested that the enormous sacred evergreen at the Temple at Uppsala was an ancient yew tree. The Christian church commonly found it expedient to take over these existing sacred sites for churches. It is sometimes suggested that these were planted as a symbol of long life or trees of death. An explanation that the yews were planted to discourage farmers and drovers from letting their animals wander into the burial grounds, with the poisonous foliage being the disincentive, may be intentionally prosaic.

Yew is also associated with Wales and England because of the longbow, an early weapon of war developed in northern Europe, and as the English longbow the basis for a mediaeval tactical system. Yew is the wood of choice for longbow making; the bows are constructed so that the heartwood of yew is on the inside of the bow while the sapwood is on the outside. This takes advantage of the natural properties of yew wood since the heartwood is able to withstand compression while the sapwood is elastic and allows the bow to stretch. Both tend to return to their original straightness when the arrow is released. Much yew is knotty and twisted, so unsuitable for bowmaking; most trunks do not give good staves and even in a good trunk much wood has to be discarded.

The trade of yew wood to England for longbows was such that it depleted the stocks of good-quality, mature yew over a vast area. The first documented import of yew bowstaves to England was in 1294. In 1350 there was a serious shortage, and Henry IV of England ordered his royal bowyer to enter private land and cut yew and other woods. In 1470 compulsory archery practice was renewed, and hazel, ash, and laburnum were specifically allowed for practice bows. Supplies still proved insufficient, until by the Statute of Westminster in 1472, every ship coming to an English port had to bring four bowstaves for every tun. Richard III of England increased this to ten for every tun. This stimulated a vast network of extraction and supply, which formed part of royal monopolies in southern Germany and Austria. In 1483, the price of bowstaves rose from two to eight pounds per hundred, and in 1510 the Venetians would only sell a hundred for sixteen pounds. In 1507 the Holy Roman Emperor asked the Duke of Bavaria to stop cutting yew, but the trade was profitable, and in 1532 the royal monopoly was granted for the usual quantity "if there are that many." In 1562, the Bavarian government sent a long plea to the Holy Roman Emperor asking him to stop the cutting of yew, and outlining the damage done to the forests by its selective extraction, which broke the canopy and allowed wind to destroy neighbouring trees. In 1568, despite a request from Saxony, no royal monopoly was granted because there was no yew to cut, and the next year Bavaria and Austria similarly failed to produce enough yew to justify a royal monopoly. Forestry records in this area in the 1600s do not mention yew, and it seems that no mature trees were to be had. The English tried to obtain supplies from the Baltic, but at this period bows were being replaced by guns in any case.

Yews are widely used in landscaping and ornamental horticulture. Well over 200 cultivars of Taxus baccata have been named. The most popular of these are the "Irish Yew" (Taxus baccata 'Fastigiata'), a fastigiate cultivar of the European Yew selected from two trees found growing in Ireland, and the several cultivars with yellow leaves, collectively known as "Golden Yew". A special use of the yew is for topiary garden sculpture, a use not uncommon for many of the more elaborate gardens of England and Scotland. In Norway, European Yew grows naturally north to Molde, but is used in gardens further north.

The precursors of chemotherapy drug Paclitaxel can be derived from the leaves of European Yew, which is a more renewable source than the bark of the Pacific Yew (Taxus brevifolia). This ended a point of conflict in the early 1990s; many environmentalists, including Al Gore, had opposed the harvesting of paclitaxel for cancer treatments. Docetaxel (another taxane) can then be obtained by semi-synthetic conversion from the precursors.

Clippings from ancient specimens in the UK, including the Fortingall Yew, are to be taken to the Royal Botanic Gardens in Edinburgh to form a mile-long hedge. The purpose of this "Yew Conservation Hedge Project" is to maintain the DNA of Taxus baccata. The species is threatened by felling, partly due to rising demand from pharmaceutical companies, and disease.

L’if commun (Taxus baccata) est un petit arbre, de 12 à 15 mètres de hauteur, de la famille des Taxacées. Très longé vif, poussant lentement, c’est un arbre qui se prête bien à la taille. L'if est un arbre qui peut atteindre 20 mètres de haut mais la plupart des individus sont généralement plus petits. La forme est variable avec une cime irrégulière et un tronc court et noueux d'où partent des branches à quelques centimètres du sol. Les formes en buisson sont également fréquentes. L'écorce de l'arbre va du brun rouge parfois très foncé voire pourpre. L'écorce est assez fine et se détache généralement en fines écailles. Les feuilles sont des aiguilles souples, plates de couleur vert foncé dessus et vert plus clair dessous. Elles mesurent généralement entre 2 et 4 cm. Les aiguilles sont insérées en spirale autour des pousses.

L’if est une espèce dioïque: les pieds femelle portent des fruits charnus, rouge vif, les arilles. Celles-ci ne sont pas toxiques et sont consommées par les oiseaux, mais la graine est toxique comme tout le reste de la plante. Les fleurs des pieds mâles produisent un pollen jaune au printemps. Cette toxicité est due à un mélange d’alcaloïdes: taxoïdes, diterpènes cycliques estérifiés par des acides banals et par des acides aminés ou des composés voisins eux-mêmes amidifiés: taxine A, B, C, paclitaxel, 10-désacétylbaccatine III, taxiphilline, cephalomannine, etc. Un seul glucoside a été isolé, la taxicatine. La sève contient une huile irritante pour le tube digestif. En définitive, une centaine de composés ont été isolés. La taxine qui est la substance la plus anciennement isolée est en général considérée comme responsable de la toxicité, mais il est vraisemblable que les autres substances le soient également plus ou moins.

L’espèce est originaire d’Europe, d’Afrique du Nord et du nord de l’Iran. En France l'if est présent localement en sous-bois de hêtraie principalement, chênaie humide, plus rarement en sapinière. Il se rencontre en plaine dans le nord en Bretagne, Normandie, Vosges et plus souvent en basse et moyenne montagne dans le sud et en Corse. Il se rencontre en peuplements reliques dans les massifs calcaires de Provence principalement à la Sainte-Baume (1148 m) à l'est de Marseille; en ubac dans la hêtraie accompagné du houx. Il peut y atteindre 17 m de hauteur et un âge de 800 ans. En moindre mesure à l'ubac de la Sainte-victoire (1011m) et des mont Aureliens (879 m), dans la forêt domaniale des Morières, et le long des cours d'eau. Dans les gorges du Verdon où il est abondant, des sujets auraient plus de 1000 ans d'âge.

Il est planté dans les jardins et les cimetières (ce qui lui a probablement évité l’extinction au cours du Moyen Âge), soit en pied isolé, soit sous forme de haies. Il se prête très bien à l’art topiaire, permettant de constituer toutes sortes de formes, cônes, boules, formes animales... Le bois d'If était très utilisé au moyen-âge pour la confection des arcs et des arbalètes. Son bois rouge foncé, très dur, est apprécié pour la fabrication de petits objets et le placage décoratif. On l'utilise également dans la fabrication de meubles (notamment en Angleterre). Il en existe de nombreuses variétés ornementales. Une des plus répandues est l’if fastigié ou if d’Irlande, à port en colonne étroite. Les glucosides extraits de l'If sont utilisés en oncologie pour traiter certains cancers mais avec beaucoup de précautions car très irritants. L'arbre était vénéré par les Celtes. Les feuilles étaient cuites pour en extraire le poison. Le médecin grec Dioscoride, chirurgien des armées de Néron, avait même peur d'être empoisonné en dormant sous ses feuilles.